The culture that defines Los Angeles

From a satire of the Hollywood underbelly, to a noir movie – and a masterpiece of resistance and rebellion – Cath Pound explores three iconic works that depict the City of Angels.

In many ways Los Angeles is a city as hard to define as it is to navigate without a car. A sprawling urban mass covering 500 sq miles (1295 sq km), it was famously described by Dorothy Parker as ‘72 suburbs in search of a city’. Its origins stretch back to the 18th Century, and yet it can still seem like a young city, having expanded alongside the film industry in the early 1900s.

More like this:

- New York cultural events not to miss

Although literally the ‘City of the Angels’, its status as the entertainment capital of the world means that it is also thought of as ‘the city of broken dreams’, the lure of success and stardom being inextricably linked with the inevitability of disappointment and defeat. The history of cinema is littered with such tales, from Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard to the Coen brothers’ Barton Fink or David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive.

The city’s rapid expansion in the early 20th Century went hand in hand with corruption of city officials and police which, along with real-life headline crimes, such the notorious Black Dahlia case, inspired a generation of hard-boiled fiction writers. Among them were Raymond Chandler and Dorothy B Hughes, whose explorations of LA’s dark underbelly would be instrumental in the development of film noir in the 1940s and ’50s.

Getty Images

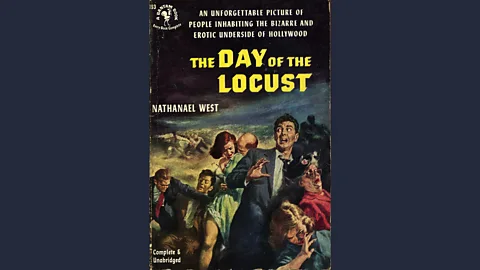

Getty ImagesIn choosing works that define LA, those that involve Hollywood and detectives therefore come naturally to mind. Nathanael West’s novel The Day of the Locust is a literary forerunner of Wilder and Lynch that mercilessly reflects the anger, frustration and violence simmering just beneath Hollywood’s shiny façade. The movie Chinatown viscerally updates the noir genre for the 1970s, while also painstakingly recreating the LA of the 1930s using surviving locations. In Judith Baca’s monumental mural sequence, The Great Wall of Los Angeles, the histories of the ethnic minorities – who appear in minor roles in both the novel and the film – are fully visualised in an epic artwork that stretches over half a mile.

The Hollywood dream

The Day of the Locust, first published in 1939, is set in Depression-era Hollywood. Peopled by wannabe stars, washed-up vaudeville performers and a bitter, deceived underclass it is, in the words of JG Ballard, “the best of the Hollywood novels, a nightmare vision of humanity destroyed by its obsession with film”.

The novel’s protagonist, Tod Hackett, is a young graduate of the Yale School of Fine Arts who has been talent-spotted and brought to Hollywood to learn set and costume design. A keen observer of humanity, he soon notes the falseness of the world around him, yet cannot help being drawn into that world when he meets Faye Greener, a 17-year-old, platinum-blonde wannabe actress.

Despite an obvious lack of talent, Faye attracts everyone around her. Those helplessly hovering include Homer Simpson – an oafish innocent who would later give his name to the character in The Simpsons – pugnacious dwarf Abe Schwartz, brainless cowboy Earle Shoop, a bit-part player in ‘horse operas’ (Westerns), and his cock-fighting Mexican friend, Miguel.

The silent chorus to these garishly compelling characters are the retired farmers, housewives and clerks who have bought into the Hollywood dream, and have come to Los Angeles for sunshine and excitement. Finding that the reality fails to live up to their expectations, they loiter on street corners, staring at everyone who passes but “when their stare [is] returned, their eyes [fill] with hatred”. Desperate for drama, they attend funerals hoping for the collapse of a mourner, and trail movie stars, hanging about outside restaurants until the police move them on.

Random House

Random HouseTod feels that these are the people who will populate the canvas he is working on, The Burning of Los Angeles, in which he will depict these bored and betrayed people destroying their surroundings in a bid to create the excitement that eludes them.

West’s novel is ultimately a biting satire on the dreams that Hollywood peddled, and those foolish enough to buy into them. Even the few successful characters are shown to live hollow lives devoid of any real enjoyment.

The Hollywood milieu is mercilessly satirised in the depiction of a party held at the home of producer Claude Estee, who lives in a fake Mississippi mansion. Desperate for novelty, he feels the need to engage in elaborate role-playing which amuses no one. “Here, you black rascal! A mint julep,” he shrieks to a Chinese servant, who promptly brings him a scotch and soda.

The tawdry nature of their world is emphasised via one of the guests, Mrs Jennings, once “a fairly prominent actress in the days of silent films”, who has found it impossible to gain work since the arrival of sound. Instead of becoming a bit-part player she has “shown excellent business sense”, and opened a brothel.

When Faye’s father dies, she is compelled to work for Mrs Jennings to meet the funeral costs, but is soon rescued by the smitten Homer, who agrees to pay for her clothes and accommodation until she finds fame. Of course the notion of someone as singularly talentless as Faye ever making it as an actress is ludicrous and this emphasis on clothing rather than training is West’s way of satirising the ‘packaging’ seen as key to Hollywood success.

Ultimately, Faye is the epitome of Hollywood’s false promise and is instrumental in bringing about its destruction. At a party she plays her admirers off against one another, before ending up in bed with Miguel. Homer discovers them, leading to Faye’s furious departure and his descent into madness.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe novel’s denouement is played out at Kahn’s Persian Palace Theatre, where a throng of demonic thrill-seekers are waiting for the stars to arrive. Here Homer is pushed to his ultimate limit, causing the crowd to riot ecstatically, having finally found something to excite them. Tod, who is also present, is swept along with the melee. He cannot help placing them, and his associates, into his fantasy canvas. Only Faye he imagines as being above it all. He sees her running “proudly, throwing her knees high”, seemingly enjoying the havoc she has created.

West knew only too well the world he was portraying. Having sold the rights to an earlier novel, Miss Lonelyhearts, to 20th Century Fox, he arrived in Hollywood full of expectations – only to see his cherished creation turned into a Lee Tracy comedy drama. He stayed to work on treatments and B-movie scripts, lodging in rundown digs like Tod, and becoming a close observer of the denizens of the city’s underbelly.

In writing The Day of the Locust, West wanted to show the sordid reality behind the dream and, by doing so, provide the means of escape from a world which had only disappointed. Ironically, he proved that LA could be the seedbed for high art, Tod’s dream painting being a metaphor for what he achieved with his novel. But tragically West never made his escape. He was killed in a car crash in 1940 and was therefore unaware of the iconic status his novel, which only sold 1,500 copies in his lifetime, would go on to have.

Love letter to Hollywood

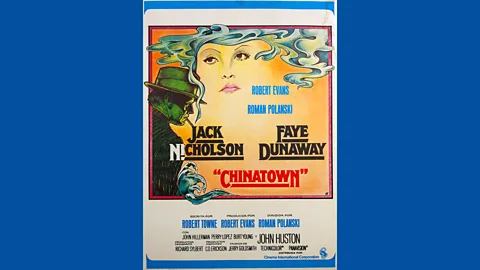

Chinatown, released in 1974, is set in the same era as West’s novel. With stunning performances by Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway, a script by Robert Towne – widely considered the greatest original screenplay ever written – and possibly the most devastating closing line of dialogue in film history, it is one of the most celebrated films of all time. A gritty reimagining of the noir genre with which LA is synonymous, it is also a love letter from the Hollywood of the 1970s to that of the 1930s, with surviving locations carefully sourced to give a feel of authenticity, which would have been impossible to create on set.

Nicholson’s character, the detective JJ Gittes, counters noir-movie myth with reality. In Chandler and Hammet, detectives were too gentlemanly to do detective work; Gittes does it, and for the money. When he is approached by a woman claiming to be the wife of Hollis Mulwray, Chief Engineer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power – who suspects her husband of having an affair – Gittes obligingly comes up with what he believes to be the evidence. But when the real Evelyn Mulwray, played with icy fragility by Dunaway, turns up at his office threatening legal action, he realises he has been set up. Assuming that Mulwray was the target, he plans to question him, but before he can do so, Mulwray is found drowned in a reservoir.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGittes is drawn into a complex web of corruption, spun by Evelyn’s monstrous father, Noah Cross. In league with the Water Department, Cross is siphoning off water in order to create drought conditions so he can purchase the dried-up land at a reduced price. Mulwray’s discovery of these plans leads to his murder.

The plot was inspired by the Owens Valley Tragedy which took place in the early 1900s. It saw many residents, mostly farmers and low-wage labourers, tricked into selling their land. The citizens of Los Angeles were then manipulated into paying $25m (£19m) for an aqueduct to bring desperately needed water to the city, a need heightened by the dumping of water into sewers to create drought conditions, only to see construction brought as far as the recently acquired land and no further. Newly irrigated, this land netted the perpetrators an estimated profit of $100m (£77m).

Despite the rot that had always been present, Towne wanted to recreate the beauty of the city before developers had torn it apart. Appropriately enough, it was a photo essay on noir author Raymond Chandler’s LA that proved it would be possible to do so. The essay showed the scant, but still significant, architecture that had survived the constant and brutal redevelopment of the city since the legendry author’s day. “There, in ringing colour, was the green Plymouth convertible. There was JW Robinson’s department store. The lazy gush of banana leaves. An imperious, piercingly white Pasadena mansion, with its porte-cochère, towering over the palms like Shangri-La,” writes Sam Wasson in The Big Goodbye, which charts the making of Chinatown.

Alamy

AlamyLocations the film was able to use to such powerful effect include Echo Park, unchanged since the 1930s, where Gittes would spot Mulwray. In a neighbourhood above the park, a lime-green apartment split by a central bungalow was chosen for Ida Sessions, the actress posing as Mrs Mulwray. Atop a hill off California Avenue, a sprawling white estate seemed perfect for Evelyn Mulwray’s home. No other buildings were visible from the lawns. There was nothing else out there, just as it had been in 1937.

The isolated house was the perfect location for the equally isolated Evelyn, the femme fatale who proves to be anything but. Throughout the film, she gradually reveals her goodness and innocence. It turns out Mulwray’s ‘mistress,’ is Evelyn’s daughter Katherine, who she is trying to protect.

Rebellion and resistance

The misuse and abuse of water at the heart of Chinatown’s plot was equally integral to the creation of The Great Wall of Los Angeles, the mural that Chicana artist Judith F Baca produced in collaboration with community groups along a stretch of the concreted Los Angeles river.

Los Angeles had been repeatedly threatened with catastrophic flooding, and in a bid to contain the danger the army began concreting the river in the 1930s, a project which continued into the 1970s and unsurprisingly created an ecological disaster. Its dystopian expanse, evoking post-apocalyptic visions of an urban wasteland, has since become ingrained in the American psyche, thanks to countless appearances in noir films of the post-war period.

Baca was approached by the US Army Corps in 1974 and asked to ‘beautify’ the Tujunga Wash section. She saw it as an opportunity to tell the stories of the ethnic groups who had shaped California – but whose histories had been ignored or erased. The mural’s central metaphor, Baca wrote in an essay at the time, would be “the tattoo on the scar where the river once ran”. It would help heal “the scars in ourselves that made it impossible for us to feel the self-esteem that one feels from knowing the history of your own contribution”.

Alamy

AlamyThe project involved more than 400 young people from diverse social and economic backgrounds for whom working on the project would be a transformative experience. As there was such a paucity of material on Native American or Chicana/o histories in the early 1970s, the mural-makers had to collaborate with oral historians, ethnologists, historians, anthropologists and community members in order to piece together their past. The results enabled them to see their identities and experiences reflected in art for the first time.

In the first section, completed in 1976, the muralists were able to correct the commonly held belief that Los Angeles was founded by Spaniards. In fact, only one of the adult members of the founding expedition was of Spanish descent. The rest were mixed race, black or Indian, a fact that is proudly made evident in the mural.

This section also revealed the major role Chinese immigrants played in the construction of the transcontinental railroad, only to suffer horrific racism leading to the Chinese Massacre of 1871, when vigilantes hung 11 Chinese immigrants in a downtown LA street.

Further sections were completed in the summers of 1980, ’81 and ’83, each time adding a decade of history. The prejudice minority groups have faced is emphasised throughout the mural. During the Depression, Mexican-US families were hit especially hard. Organised labour resented competition from Mexican workers as unemployment rose and, bowing to union pressure, authorities ‘repatriated’ hundreds of thousands of people of Mexican descent. As many of these people were US citizens, it was a gross violation of civil liberties. These events are still often missing from the history books, but in 2012 LA County issued an apology following decades of lobbying from activists.

A section of the mural entitled Division of the Barrios and Chavez Ravine shows the devastating effect of the construction on inner city, working-class and ethnic communities. Freeways encircle and divide a Chicano family while their pylons crush through the roofs of houses below. The Dodgers Stadium is depicted descending like a spacecraft into the Chavez Ravine where a Mexican community was forcibly removed to enable its construction. The mural focuses on the defiance of the Arechiga family, who famously resisted eviction but roused anti-Mexican sentiments in the process. A female member of the family is shown raising her fists in fury to emphasise this pioneering action of resistance, which paved the way for the Chicano civil rights movement in the late 1960s.

Indeed, there is a sense of rebellion, defiance and pride running throughout the mural, despite the horrific abuses that it reveals. Biddy Mason was an ex-slave from Georgia who fought extradition under the fugitive slave laws, became a wealthy woman and founded the African Methodist church in Los Angeles – she is celebrated in the painting, as is Mrs Laws who fought housing discrimination during the World War Two years.

The Jazz Age discriminated against the performers it revered, banning them from white-only hotels, but Los Angeles had the Dunbar hotel. Owned and run by two prominent members of the African-American community, it was built entirely by black contractors, labourers and craftsmen, and financed by black community members. The mural shows Billie Holiday rising above the luxury venue that welcomed her and other black performers with open arms.

Alamy

AlamyThe mural counters the erasure of the ethnic presence in LA by portraying diverse, marginalised groups, and in doing so contests the whitewashed version of LA popularised by Hollywood. At present, the mural ends with a celebration of ethnic-minority athletes and a torch-bearing female runner, dashing ahead into what will eventually be a section representing the civil rights movement. Discussions are already taking place about what will appear in the panels depicting the 1960s onwards, and when the mural is completed, at a yet-to-be-decided date, it will stretch for almost a mile.

The Day of the Locust and Chinatown will always remain classic depictions of LA but as Baca’s mural shows, there are many more stories that can be told. As The Great Wall of Los Angeles expands, perhaps these stories will begin to appear more on screen and in literature as well.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.