Saint Malo: The first Asian settlement in the US

Alpha Stock/Alamy

Alpha Stock/AlamyBefore the US was a country, Filipinos were likely living in raised, stilted homes over the swamplands outside New Orleans.

Just five miles downriver from the ornate, iron-lace balconies of New Orleans' French Quarter, bright stucco buildings and raucous bars give way to a more serene landscape stroked in wild marsh grasses and thick mud. Fishermen sell fresh shrimp along the roads that cut through St Bernard Parish as their boats bob in the bayous nearby. The quiet, 200-year-old suburb is famous for its fishing industry and unique geography, appearing to rise up on a map from Louisiana's eastern coast like a cresting wave before spitting dozens of islands and marshes into the Gulf of Mexico.

Here, on Lake Borgne, where laughing gulls dive for speckled trout and sudden squalls regularly batter boats, is where Saint Malo once stood, the first permanent Filipino settlement in the United States and the country's oldest-known permanent Asian settlement.

The story of Louisiana's rich and diverse bayous is often told through the melding and mixing of Spanish colonisers, French Acadians, Native Americans and both enslaved Africans and free people of colour. But throughout history, there has been one largely forgotten ingredient missing from this rich cultural stew: before the US was a country, Filipinos were likely living in raised stilt bahay kubo-like homes built over the swampland outside New Orleans.

Daniel Borzynski/Alamy

Daniel Borzynski/AlamyFrom these "floating villages" they established the community's fishing industry and introduced Louisiana to dried shrimp – produced by boiling, brining and sun-drying the crustaceans to preserve and concentrate their flavour. Dried shrimp were an important commodity in the days before refrigeration, and today, many locals still eat them as a snack or use them as an umami-rich ingredient to flavour stocks, sauces and gumbos.

Alongside later Chinese immigrants, these so-called "Manilamen" transported dried shrimp all over the world. According to Laine Kaplan Levenson, a host of the Southern Foodways Alliance's Gravy podcast, by the 1870s, the swamps of Louisiana hosted more than 100 shrimp-drying platforms, each more than three football fields long. "In effect, dried shrimp globalised Louisiana's seafood industry" and laid the foundation for Louisiana's modern-day shrimp industry, she notes on the podcast episode.

But how these Manilamen arrived in Louisiana is a mystery as murky as the bayou itself. Some historians believe they came on Spanish trade vessels in the mid-1700s. Others believe Filipino sailors and servants plying the Manila-Acapulco trade route jumped ship in the New World and sought refuge in the Gulf, whose marshy, flood-prone landscape resembled their homeland. Some British colonists even talked of "Malay pirates" that were part of French pirate Jean Lafitte's band of smugglers who captured Spanish galleons.

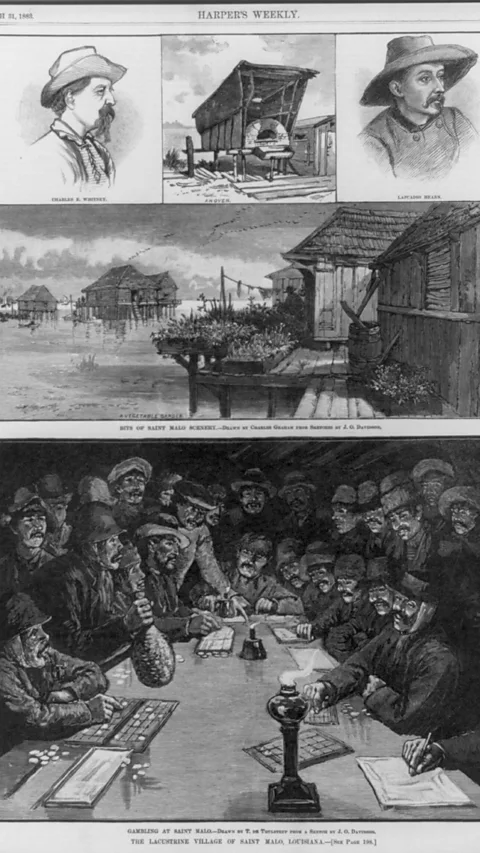

One of the oldest-known accounts of Saint Malo comes from an 1883 article in Harper's Weekly, when the writer Lafcadio Hearn painted a dream-like picture of the "floating" community: "Out of the shuddering reeds and banneretted grass… rise the fantastic houses of the Malay fishermen, posed upon slender supports above the marsh, like cranes or bitterns watching for scaly prey."

Alpha Stock/Alamy

Alpha Stock/AlamyHearn noted that the community had existed for roughly 50 years before his visit, but in a story for History.com, Filipino American historian Kirby Aráullo wrote that, "according to oral traditions, there was already an existing Filipino community there by 1763 when both the Philippines and Louisiana were under the Spanish colonial government in Mexico".

According to Randy Gonzales, a fourth-generation Filipino Louisianan, historian and professor of English at the University of Lafayette, the Manilamen saw opportunity in the Louisiana Gulf, an area that many people found too wild and hostile. Though mosquitoes often swarmed and hurricanes battered it, the Manilamen were used to typhoons in the Philippines. Like the Philippines, St Bernard Parish was ruled by Spain; Spanish was the primary language in the area, and the Manilamen shared Spanish heritage with many residents. It also wasn't very populated, offering economic opportunities for those who knew how to harness its wild spirit.

The Filipino settlers already knew how to make nets and catch shrimp from life in the Philippines, explained Liz Williams, founder of the Southern Food and Beverage Museum in New Orleans. But it was in the swampy marshes of St Bernard that they pioneered a method for preserving and drying the crustaceans. According to Williams, after boiling the shrimp in brine, the Filipino settlers laid them out on platforms and dried them for several days. Then, they shuffled over the shrimp to remove the shells.

"[They would] put some kind of canvas or other fabric over their feet, and they would walk on nets that were up above the water in the marshy area and walk on the dried shrimp," she said. The shrimp shells crumbled off, but the dried shrimp, made tough by the salt from the brine, didn't break. The shells fell back into the marsh, while the shrimp stayed on the net. They called this the "shrimp dance".

Thanh Thuy/Getty Images

Thanh Thuy/Getty Images"They realised that [dried shrimp] could be shipped out and go all over the world because we have so many shrimp and so many shrimp seasons here," Williams added. "You have river shrimp, you have white shrimp, you have brown shrimp, and they don't all run at the same time."

John Folse, a chef, restaurant owner and expert on Cajun and Creole cuisine, remembers there always being a bucket of dried shrimp on his childhood home's back porch in Louisiana's St James Parish during the 1950s. Like many Cajun families, his family ate what they harvested, hunted or preserved themselves. And like the Filipino settlers, Folse's grandfathers also sun-dried the shrimp. They caught them, threw salt over them and spread them on a table outside during the day and covered them at night. "You see, [dried shrimp] was almost like a gift that just kept on giving through the season when everything else was out," he said. "We could always count on the fact that we had preserved that particular ingredient."

"With bland vegetables like eggplants and squashes from our gardens, the dried shrimp were perfect for bringing that explosive flavour that we just couldn't get out of putting crab meat or regular shrimp into it," Folse added. "Smoked sausages like smoked andouille were really, really expensive, and dried shrimp were available to us all the time. So, when I think of it, I think, 'My god, what in the heck would we have done without it?'"

To visitors today, dried shrimp is most visible hanging in little bags in the check-out lines of the local grocery stores. These bags bear names like Blum & Bergeron – typical Louisiana surnames that show just how ingrained the product is in the state's culinary landscape. In fact, it's unlikely that many locals recognise the food's early Filipino origins, and that's because the history of Saint Malo itself has largely been forgotten.

Stephanie Jane Carter

Stephanie Jane Carter"These stories get lost over time," Gonzales said. "In the 20th Century, the reason these stories [got] lost is because of assimilation – and in some ways, because of segregation. Filipinos are brown. Well, when you're brown, you can be white or black, depending on who's deciding. And so, my grandmother had to go to school and say, 'Look, my son is white' so he wouldn't go to the black school, which wasn't funded as much. There were real pragmatic reasons to kind of let that identity slip."

There are also physical reasons why the story of Saint Malo has been lost. According to Gonzalez, there are so few artefacts and records of the settlement that piecing together the Manilamen's history has proved difficult.

Marina Estrella Espina, author of the book Filipinos in Louisiana, was one of the first modern historians to document the story of the Filipinos at Saint Malo. Between 1970 and 1990, she tracked down descendants of the Manilamen, and gathered family photos, birth certificates and stories, which she stored in her New Orleans home. But when Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005, her home took on 11ft of water, literally washing away her research. "Every 50 years, nature seems to diminish the Filipino history here," she said in a 2006 interview.

The loss was devastating. According to a spokesman for the Filipino American Historical Society, "Espina's research was the foundation of Filipino American history."

Stephanie Jane Carter

Stephanie Jane Carter"We've lost so much through storms," Gonzales said. In fact, much of the actual land near the Saint Malo settlement is slipping away. St Bernard Parish is famous for its vanishing coastline, and could lose more than 70% of its land area over the next 50 years without intervention. As the remains of the land that hosted the Manilamen slowly disappear into the Gulf of Mexico, it seems like a dark metaphor for the history of the site itself.

Still, the story of these Filipino settlers is finally being recognised. Gonzales, a prominent researcher on the history of Filipinos in the US, authored the book Settling St. Malo: Poems from Filipino Louisiana, and has written many essays exploring the topic. In 2019, the Philippine-Louisiana Historical Society erected a marker to commemorate Saint Malo's history, and Gonzales wrote the text for the plaque. In 2012, the group erected another historical marker roughly 45 miles south in Barataria Bay to commemorate Manila Village, a later Filipino shrimp-drying village that lasted from the turn of the 19th Century until 1965 when Hurricane Betsy destroyed it.

The Saint Malo marker is located at the nearby Los Isleños Museum Complex, just a few miles from where the village would have stood, now a popular fishing spot devoid of any of the settlement's early stilted structures. The Manilamen's story is also highlighted in a new exhibit examining the role of Filipinos in Louisiana history at the SoFAB Research Center at Nunez College in St Bernard.

So much of the Manilamen's story has vanished, either because of storms or assimilation. But as Gonzales said, exploring it reminds people that "Filipinos were a part of it, and we are still here [in Louisiana]. I'm telling the Filipino story to talk about a story that's been kind of lost – and [as a warning] that all of our stories can be lost in this way."

Rediscovering America is a BBC Travel series that tells the inspiring stories of forgotten, overlooked or misunderstood aspects of the US, flipping the script on familiar history, cultures and communities.

---

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.