The Indigenous rebellion that inspired Peru's independence

Heather Jasper

Heather JasperA battle between Peruvian rebels and Spanish colonisers in the tiny Andean community of Sangarará was the beginning of a doomed but influential uprising.

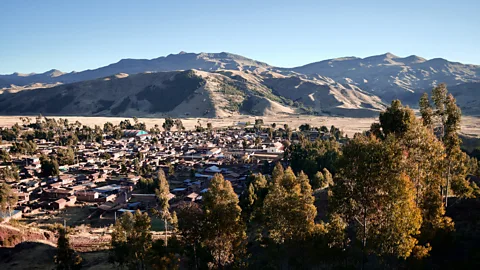

"Amigo, the battlefield was right here," said Rodolfo Román Sandoval, gesturing around the plaza of Sangarará, the Andean village where he grew up. Set 3,800m high in the Andes and dramatically ringed by mountain peaks, the place had a sleepy feel; there were more sheep crossing the street than people, and the silence was broken only by the occasional barking dog or braying donkey.

Román remembers when electricity came to town; and told me that as late as the mid-1990s, the people of Sangarará still used a barter system in lieu of money. Currently, he's renovating his childhood home in the village to become a tourist hostel and pub. There's not much in the way of tourist infrastructure here yet, save a few rustic hostels and a pollo brasa (rotisserie chicken) restaurant with some of the best salsa picante I've ever tasted. But Román is one of a group of people who thinks this is a place worth discovering. That's because this dusty village was an early and crucial stop on the road to Peru's eventual independence.

Like many rural Peruvian towns, the plaza is eclipsed by an ancient and disproportionately large church. Directly facing the church stand two statues – Tupac Amaru II and Tomasa Tito Condemayta – wielding weapons. The rebellious spirits of these two figures remain deeply embedded in Sangarará's culture, as this was the site of one of the fiercest conflicts – and one of the most important Indigenous rebellions – in Peruvian history.

Every Peruvian knows the story of how, in 1781, the rebel leader Tupac Amaru II was executed by the Spanish Empire in Cusco's central plaza. Forced to watch his wife and son killed in front of him, his tongue was then cut out, and he was drawn and quartered then beheaded. His body parts were sent to be displayed in the Andean villages from which he had drawn his support and troops.

What is less known are the beginnings of his brief Indigenous rebellion in the tiny Andean community of Sangarará. A battle on 18 November 1780 between the Peruvian rebels and the Spanish colonisers in this town marked the true start of Tupac Amaru II's doomed but deeply influential uprising, which ended in March 1783.

Heather Jasper

Heather JasperThe Battle of Sangarará was one of the few major victories of his rebellion, and would eventually incite revolutions throughout much of South America – including Peru's own independence 40 years later. This year's bicentennial celebrates the country's official independence, but those seeds of revolution were planted several decades earlier by Tupac Amaru II, and his campaign is viewed by many Indigenous as the true beginning of the long road to freedom from Spain.

Today in Peru, Tupac Amaru II is a near-mythical figure. Born José Gabriel Condorcanqui, and ostensibly of royal Inca blood, he was a travelling merchant, which gave him a precise understanding of the devastating economic and living conditions in the impoverished Andean villages – conditions imposed on them in brutal fashion by the Spanish authorities.

You may also be interested in:

• A new history on the Inca trail

• South America's most underrated city?

• The truth about the humble potato

"Tupac Amaru II saw how the Indigenous people were forced to work for the Spanish – dawn to dusk, 12 hours every day. He saw the exploitation, the abuse and the branding [of Indigenous people]. This is what made him start to organise," said Sangarará native Enrique Arnedo Oimas.

But Tupac Amaru II wasn't even present for the biggest victory of his own rebellion. According to Arnedo and other locals, he was stationed with his troops nearby but didn't arrive until the battle was over. Instead, the rebels were led by a little-known figure in Peru's history: Tomasa Tito Condemayta, "the heroine of the Battle of Sangarará," said Arnedo.

Tomasa Tito Condemayta was a cacica (local leader) from nearby Acos who also had a home in Sangarará. She was the only known woman in the region to be a cacica, and personally led her own battalion of all-women warriors, armed with slings and bows. Her role in rallying and organising Indigenous women was pivotal for the rebellion. Arnedo noted that previously, "she led the battle at the Pilpintu bridge, and another at Acos. That's why Tupac Amaru II sent her to Sangarará – because she was a good leader and strategist."

Heather Jasper

Heather JasperAccording to Arnedo, before the battle local children raised the alarm that the Spanish army was on its way from Cusco to Sangarará. "They were in the mountains watching their sheep and saw the army coming. They ran to tell Tomasa... when the Spanish arrived, all of the people came to fight. Men, women, children, everybody was armed with rocks and farming tools."

Today, the plaza's adobe church with its tiled roof lies at the heart of the controversial battle. Sections of the church have been reconstructed, but parts of the original foundations and even some wall paintings remain. Marta Esperanza Pacheco, who has been the church's caretaker for 40 years, led me into a back room, one with a baptismal font and a very small – but important – window.

"During reconstruction, they uncovered a pile of bones up to here," Esperanza said, gesturing to her waist.

When the Spanish forces arrived, it began to snow and the soldiers bunked down in the church – perhaps believing they would be safe there, or unaware of the gathering rebels. There are those who believe Tito Condemayta set the church aflame on purpose. More – particularly locals – believe she was attempting to smoke the Spaniards out of hiding and the efforts got out of control. Still others say that the Spanish accidentally detonated explosives while within the church.

"They turned the Spaniards into chicharron (fried pork belly/rinds)," said Arnedo of the rebels, with a sly smile.

Though the source of the blaze remains unclear, what is not contested is that there was a massive explosion and almost all the Spanish soldiers were either killed right then or when they fled outside – except for three. These men donned saints' clothing found in the church and escaped through the tiny window in the rear of the building.

"The people said, 'Look, even the saints are fleeing the church!'," said Gregorio Cruz Machaki, the mayor of Sangarará.

Heather Jasper

Heather JasperWhile it galvanized Tupac Amaru II's campaign with Peru's Indigenous people, the burning of the church and the ensuing slaughter of Spaniards turned many Catholics and mestizos (people of mixed ethnic Peruvian and European descent) against the cause.

In the end, Tito Condemayta was brutally executed along with Tupac Amaru II in Cusco's Plaza de Armas. Not much is known of her life before the rebellion, but Erika Quinteros, author of the recently published Tomasa Tito Condemayta: Una Historia de Valor y Coraje (Tomasa Tito Condemayta: A Story of Courage), noted that Tito Condemayta did all this "during a time when many Peruvians believed women had no role to play in military, or politics".

"I was shocked that I'd never heard her story, even though I'm Peruvian, and my grandmother was Indigenous. In Peru, our national heroes are mostly white men, but many women have been involved in historical moments in Peru – but they were wiped from our history," said Quinteros. "With this book, I wanted to show [Peruvian] children that there are heroes that look like them."

Román's mother, Eugenia Virgina Sandoval Quispe, agrees. She was born in Sangarará and attended school there and in Lima – but in Lima she never learned of her village's rich history, or Tito Condemayta's role. That has changed: her daughters were taught these things, and she believes the women of Sangarará will be more inspired to become leaders and enter into politics.

"Now, I see the children in school are more interested in history. They want to know. My daughters know the history… and I've begun to research more, myself. I am more interested in what happened here," she said.

Heather Jasper

Heather JasperThe rebellious spirit of Sangarará isn't just a relic of history. Due to a long history of clashes with police, federal officers (formerly Guardia Civil) have not set foot in the town since the 1940s. In the 1920s, 150 years after the Battle of Sangarará, there were violent clashes with local Spanish landowners over working conditions. Years later in 1942, Arnedo was taken prisoner by government forces at only 12 years of age, after a bloody dispute over mining rights in the area.

"We've always been rebels here. We've always confronted authority," said Arnedo.

Despite its deep history of social unrest, today Sangarará is a friendly, quiet village that's safe to visit. And among locals, there's a consensus that the village's place in history isn't getting the recognition it deserves.

"Here is where Túpac Amaru's rebellion started, where he organised with other leaders like Tomasa Tito Condemayta," said Cruz. "We want the Peruvian government to legally recognise 18 November as a historic date," he said.

Cruz is keen to encourage tourism to Sangarará, and he's got an ace up his sleeve: nearby sits one of the grandest but least-known ruins in Peru, the iconic Waqra Pukará (Quechua for "horned fortress"). The site's origins are steeped in mystery, although it is known that the Chanca civilisation occupied it before it was appropriated by the conquering Inca.

David Mendoza Valdivia/Getty Images

David Mendoza Valdivia/Getty ImagesAt an elevation of 4,100m, the ruins are nearly twice as high as Machu Picchu. From town, it's a simple matter to hire a car to get closer to the ruins, and about a two- to three-hour hike from that point. The fortress is a mix of primeval elements and classic Inca touches, and looks more like something from the land of Mordor than Peru.

In addition, the site of Tito Condemayta's home in Sangarará is being converted into a museum, and a hotel has been built at one of the nearby lakes to support tourism to Waqra Pukará. There's also talk of developing horseback routes to the ruins in addition to the walking trails already established.

"This is an important place. But it has been forgotten," said Arnedo.

---

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

{"image":{"pid":""}}