How would Wainwright view those walking his Lake District fells today?

Chris Butterfield/Ken Shepherd

Chris Butterfield/Ken ShepherdThe Christmas break is a busy time for the Lake District, with holidaymakers and day-trippers taking advantage of a bit of down time to "tick a Wainwright" - the practice of climbing one of 214 peaks featured in Alfred Wainwright's famous guides. But what would the man who became synonymous with these fells think of the practice today?

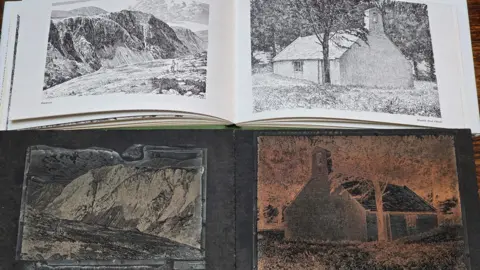

Alfred Wainwright is known for painstakingly compiling the seven volumes of his Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells, complete with hand-drawings detailing the features of the peaks.

He fell in love with the fells during his first trip to the Lake District in 1930, aged just 23, at a time when few were found wandering the paths.

It was an experience he recalled in a series of interviews broadcast before his death and recently re-released as part of a Secret Cumbria podcast on BBC Sounds.

"I found it so wonderful," he said. "I never dreamt that there could be a landscape like that - I think that was the incident that changed my life."

Brought up among the mills and factories in Blackburn, Lancashire, he had never been able to afford to get out of the town until then.

When he managed to save £5, he headed for the Lake District, where he lodged in a bed and breakfast for just five shillings.

According to an inflation calculator by the Bank of England, it would be about £14 in today's money - barely enough to pay for a night's camping now.

'Alone all day'

David Rigg owned Titus Wilson in Kendal, which printed Wainwright's books for 40 years.

"He very much enjoyed the fact that he opened up the fells for an awful lot of people who wouldn't have had the confidence or the nerve to go on a fell walk," he says.

Even in his lifetime, the popularity of the Lake District changed dramatically, as Wainwright hints to in one of his later interviews before his death in 1991, aged 84.

"Of course, once you're out of the valleys then it's just as it used to be, you can be on your own all day along the fells and enjoy everything," he said.

Chris Butterfield

Chris ButterfieldThe Lake District is now a Unesco World Heritage site, with 18 million visitors annually.

Irresponsible parking and traffic are among the biggest issues facing the national park today, with seasonal buses travelling to hotspots to try and ease pressure on the roads - a practice that Wainwright would likely have approved of.

Before moving to Kendal in 1941, he would come to the Lakes on the first bus from Blackburn and return home on the last one of the day.

"He never drove, he never had a car," recalls Mr Rigg.

"[He] encouraged people out all over the Lake District and I think that's what he was proud of - how much pleasure he caused to tens of thousands of people by encouraging them to go for a walk, not pollute the environment, not do anything with machinery, get on a bus and go for a walk."

Another issue that comes with high levels of tourism is the pressure on mountain rescue services, which reported a record number of call-outs in 2024 to help lost and injured walkers.

Lost walkers were exactly what prompted Wainwright to first start compiling his guide books.

In one interview he said: "Although there weren't many people walking [the fells] in those days, I was always coming across people who were lost - there were no guide books of the fells and it was important that there should be."

Wainwright was trying to fix an issue that is still affecting the Lakes today.

On one hand, the landscape has barely changed since his first days climbing his beloved fells, but on the other, how people do it - and how many people want to do it - is proving a challenge.

Chris Butterfield

Chris ButterfieldWhat would Wainwright think of today's Lake District? He certainly made it more accessible and tried to give people the tools to enjoy it responsibly.

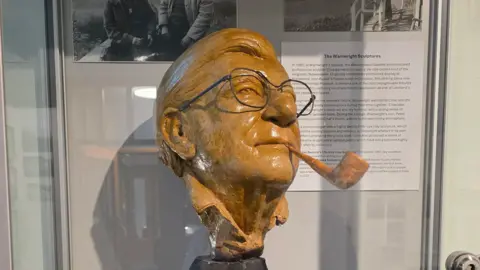

An anecdote by sculptor Clive Barnard may go some way to answer that question.

When Wainwright asked him if he walked with his dog in the Lakes, the sculptor said he did not.

Asking if he should, Wainwright told him he "definitely" should not.

"He said it distracts - a dog distracts, a child distracts. He said somebody walking with you distracts because they want to talk to you," Barnard recalls.

"He said, 'I've got eyes, I can see and I want to see, but they want to tell me what they see - and somehow the magic is lost'."

Chris Butterfield

Chris Butterfield