Rent controls are coming to the UK - but they're not a guaranteed win for tenants

BBC

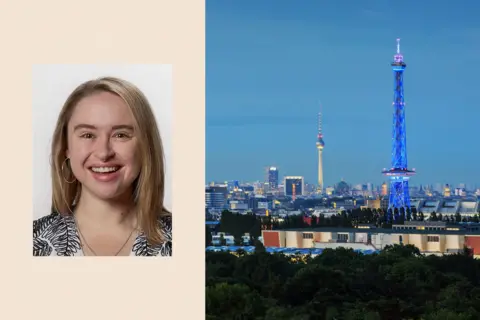

BBCWhen Emily Grant moved to Berlin in 2023, she was warned how difficult it would be to secure somewhere to live. "You'll find a job in a month," a friend told Emily, who works at a marketing agency. "But it might take one or two years to find an apartment."

Emily, 35, who is originally from Atlanta, Georgia, thought her friend was joking, but quickly realised "how competitive and how scarce the apartments are". After three months of searching, she eventually found a room in a shared apartment in Schöneberg-Wilmersdorf in the city's south-west for €800 (£692) a month - relatively modest compared with, say, New York or London.

But, Emily says, "the price just doesn't matter if you can't get a home". She blames a system of rent controls briefly introduced in Berlin in 2020 in response to spiralling rents for her delay in finding a flat - although the authorities in Berlin do not agree.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSoon, a different system of rent controls will be coming to the UK. In Scotland, councils will be allowed to ask the government for permission to impose rent controls on private properties in some areas. This is expected to happen by spring 2027. Temporary rent controls introduced in October 2022 expired in spring 2025.

There have been calls for rent controls elsewhere in the UK, too. Sadiq Khan, the mayor of London - where the average monthly rent in December 2025 was £2,268, the highest in the UK, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) - has long lobbied the government to cap rents.

Greater Manchester Mayor, Andy Burnham, too, says capping rents should be on the table. Speaking before he was blocked from standing as Labour candidate in a forthcoming by-election, he tells me: "If you're going to get serious about tackling the cost-of-living crisis, this is something you have to look at."

But many economists say rent controls can create as many problems as they solve. Landlord groups also warn they can exacerbate the housing crisis by putting owners off renting out properties - and this, critics argue, is what happened in Berlin. Supporters of controls say these criticisms don't recognise the range of different approaches that can be taken.

The term "rent controls" covers a wide range of arrangements around the world and sounds like a renter's dream. But amid the warnings of unintended consequences, can they actually function successfully?

Renters' rights vs landlords' nerves

Each day Chloe Bryceland, 23, has a four-hour round commute between her rented flat in Dundee and her job as a client administrator in Glasgow. She has been hunting for a flat nearer her workplace since July last year.

Right now, Chloe says she spends about a third of her income on rent, but when she moves to Glasgow she anticipates that will be more like 60%. Private monthly rent prices in Scotland's largest city rose to an average of £1,262 in November 2025, up 5.9% from the previous year, according to the ONS.

Across the UK as a whole, the average monthly private rent in the UK was £1,368 in December 2025 - up 4% on 12 months previously, the ONS says.

"I'm not really too sure how anyone's able to keep their heads afloat," Chloe says.

Chloe Bryceland/Getty Images

Chloe Bryceland/Getty ImagesIt's the likes of Chloe that the Housing (Scotland) Act, passed in September 2025, aims to help. It is "designed to help stabilise rents in areas where market rents have been increasing particularly steeply", the Scottish Government says. Caps will apply during and between tenancies so there is "no incentive to evict tenants to increase rent".

Councils in Scotland will be given powers to limit rent rises to the consumer prices index (CPI) rate of inflation plus 1%, up to a maximum of 6%.

Not everyone is convinced this is the right approach.

Although figures show the total number of rental properties in Scotland has risen since 2022, John Blackwood, chief executive of the Scottish Association of Landlords, points out that there are fewer registered landlords. He says he worries it might become "no longer financially viable to let properties in Scotland".

Others say the legislation doesn't go far enough. Ruth Gilbert, from Scottish tenants' union Living Rent, says the proposals have been "watered-down", with no provision for a freeze.

Some homes will be exempt, including mid-market rents and flats built exclusively for renting, such as student flats, to ensure "a robust supply of homes", the Scottish Government says. But Gilbert argues this will create a "two-tier" system - illustrating the difficulty of pleasing both sides.

A brief history of rent controls

Rent controls have existed for over 2,000 years, according to Dr Konstantin Kholodilin of DIW Berlin, the German Institute for Economic Research - there is evidence of rents being frozen for a year during the Roman Empire, he says.

During the 20th Century, there was an "explosion" of rent controls, he says. The UK, for instance, introduced them in the wake of housing shortages during World War One. By this time some 60 countries had some form of rent control and by WW2 it was over 100, Kholodilin says.

There is no one type of rent control. For example, in England's social housing sector, there are caps on annual rental increases. In some countries, soon to include Scotland, this model will also apply to the private sector. Under other, stricter, so-called "first-generation" rent controls - like those briefly implemented in Berlin - rents stay frozen or have a maximum price ceiling.

Even critics of controls agree they are good for sitting tenants.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut Kholodilin says cities like New York and Stockholm have developed two-tier systems, where some properties are subject to controls and others are exempt. Ingrid Gould Ellen, professor of urban policy at New York University's Wagner Graduate School, says tenants in rent-controlled properties are less likely to move and give up a good deal - meaning they don't always go to those most in need.

Ruth Gilbert says this is all the more reason to introduce a "universal" rent control system with "no loopholes".

Kholodilin also warns that properties become "under-repaired" when controls are enforced - Chris Norris from the UK-based National Residential Landlords Association says this is because landlords have "no motivation to invest".

All this has long been the orthodox position among housing economists, but Dr David Madden of the London School of Economics (LSE) says the "orthodoxy is changing". Controls can work, he says, as "part of a broader strategy" that includes social housing and building affordable homes.

"If you look at what Scotland is implementing, it's extremely flexible," he adds. "This is not the blanket hard cap of generations past."

What happened in Berlin?

In 2013, legislation was introduced in Germany, where more than half the population rents, to allow regions with "tight housing markets" to limit the amount landlords can increase rent by to around 15% over three years. A "rental break" also means landlords cannot charge 10% above market rate on new tenancies.

However, in 2020 "in Berlin, they thought this nationwide policy was not sufficient", says Kholodilin, and the city voted to freeze rents at pre-pandemic levels. This went well beyond national German policy or indeed Scotland's forthcoming system.

Berlin's policy was overturned around a year later by Germany's Federal Constitutional Court, but not before making an impact, critics say.

According to a study by Kholodilin and other researchers, the median number of rental units advertised each week in Berlin fell from approximately 640 before the announcement of the policy to 223.5 after it was introduced. The study also found that the number of Berlin dwellings converted from rental to owner-occupation rose from 12,700 in 2019 to 19,200 in 2020 - a 51% rise.

A spokesperson for the Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development, Construction and Housing says it sees no connection between the rent control law and a decrease in supply.

"The advantage of all these rental regulations is undoubtedly that even people with average incomes can still rent apartments in Berlin, especially in the city centre," the spokesperson says, adding that the reason fewer properties were advertised following the freeze was because demand was so high there was no need to advertise online.

Nonetheless, rent control critics see the episode as a vindication. Following Berlin's example would "run the risk of losing housing supply", says Christine Whitehead, emeritus professor of housing economics at LSE.

Madden cautions against jumping to conclusions. The freeze "was only in place for one year" and scholars would need "a longer period of evidence before we can really come to a decision about it", he says. It's notable that the freeze remained popular among the city's renters, he adds.

The French alternative

This is a global debate. "Across the world, we've seen rent increases and housing cost increases generally have surpassed increases in income," says Gould Ellen.

In November 2025 Zohran Mamdani won election as mayor of New York City under the slogan "Freeze the rent".

Some pro-controls campaigners point to France as a success story.

Under Francois Hollande, who was president from 2012-17, controls were introduced in areas of high demand. Guillaume Aichelmann from Parisian tenants' association CLVC says the policy has broadly worked: "The cost of rent is stabilised and in some cases it has decreased."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAccording to one study, the average rent drop in Paris between 2019 and 2023 was somewhere between 3.7% and 4.2% and researchers found no evidence of a reduction in supply.

The controls are less severe than those introduced by Berlin in 2020 - prices are set per square meter by a panel and the amount paid depends on the area and facilities the apartment has. Landlords who don't comply face penalties.

But there are loopholes: Aichelmann says some have switched to short-term lets, which are exempt. Norris says when rent controls are introduced, investors shift property to "other niche markets or different sub-markets".

Could the rest of the UK follow suit?

The Renters Rights Act, which takes effect in England in May, includes measures to ban no-fault evictions, gives tenants stronger powers to challenge rent hikes and ensures landlords can only raise rents once a year - previously, some had found ways to increase them more often.

"The government is committed to supporting renters," a spokesperson for the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government says - but the law stops short of controlling rent prices.

But while Andy Burnham says the Act is "very good in many ways", he tells me it is time for "a much more serious debate about renting" and says he "absolutely" would introduce controls in Greater Manchester if he had the power.

He says he doesn't have a clear plan on what he would do but talks about what would be a more limited targeting of landlords who are not hitting certain standards. This might mean "you don't get the right to increase your rent if your property is below what is an acceptable standard", he suggests.

PA Wire

PA WireOthers would go much further. As well as backing rent controls, the Green Party of England and Wales has committed itself to phasing out private landlords. There is also pressure from the campaign group Generation Rent who last year delivered a petition to No 10 signed by 57,000 people backing rent caps.

Westminster government insiders, however, argue rent controls mean a worse deal for tenants through higher rents at the start of tenancies and by encouraging unregulated subletting.

Shadow Housing Secretary James Cleverly says landlords are already fleeing the market and "rent controls would only drive more of them away".

In 2022, changes to the law in Wales took effect offering tenants greater protections - landlords now have to give six months notice before a no-fault eviction, compared with two months previously. Last year, Northern Ireland introduced limits on how often landlords could raise rents, where previously there were none. But both nations also resisted calls for rent controls.

There's a balance to be struck, Gould Ellen says: "I think that the challenge here is: how do you protect tenants at the same time that you ensure the long-run financial stability and viability and sustainability of these buildings?" Politicians will remain under pressure to achieve both.

Additional reporting by Florence Freeman, Jade Thompson and Jon Kelly

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published - click here to find out how.