The harm caused by dehumanising language

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe words we use when describing others can be important if we want to avoid a slide to something worse.

Sticks and stones famously break bones – but words can also hurt you. It is there in the charged rhetoric from both sides of the conflict unfolding in Israel and Gaza, just as it can be found in the language of clashes around the world: old tropes and name-calling that seek to paint whole groups of people as somehow less than human.

Those observing the current conflict in Israel and Gaza will have heard voices from both sides refer to each other as "animals" and "beasts" in various forms. From the mouths of political leaders and media commentators it can at first appear to be little more than theatrical flourish – something said for effect. But a body of research suggests there are reasons why we should all be hyper-vigilant about the words that we use and hear.

"Hated, despised and distrusted groups are often described in dehumanising ways – both blatantly through animal metaphors and more subtly by using less humanising, distinctively human descriptions," says Nick Haslam, a professor of psychology at the University of Melbourne in Australia. "There's surprisingly little evidence that dehumanising language causes violent behaviour, but plenty of evidence says it accompanies it. People who dehumanise others are certainly more likely to treat them badly."

The use of animalistic slurs, for example, have been found to increase people's willingness to endorse harm by changing perceptions of social desirability, according to research by psychologists Florence Enock, a senior research associate with the Alan Turing Institute's Online Safety Team, and Harriet Over, from the University of York, UK. In an experiment, they created a set of fictional political groups and described them in different ways to the study's participants. Some descriptions included words like "snakes" or "cockroaches", while others included negative human descriptors. "The participants who rated the parties described in animal terms said they were more undesirable, and had more willingness to harm those groups," says Enock.

Research into dehumanisation was catalysed after World War Two, where psychologists tried to examine how populations could be led into war and genocide. The memoirs written by the chemist Primo Levi about his time in Auschwitz, provide just such an example. Recent analysis of them by Adrienne de Ruiter, assistant professor in philosophy and humanism at the University of Humanistic Studies in Utrecht, the Netherlands, found that the dehumanisation he and others faced in the Nazi's death camps functioned to strip them, in the eyes of their guards, of any moral reasons against mistreatment. Rather than being literally thought of as an animal or a monster by their perpetrators, they were seen as humans who didn't count.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPsychologists use terms like othering as well as "the outgroup/ingroup effect" to talk about the space in which dehumanising language occurs. In social psychology, the outgroup homogeneity bias studies the concept that you're likely to see members of a group different from your own as similar to each other. In other words, they are all the same, whereas we are all diverse individuals.

In an illustration of this effect, a study from 2013 conducted by psychologists at the University of Kent, in the UK, found that the more Christian participants associated dehumanised words in connection with Muslims, the higher their self-reported willingness to support the torture of Muslim prisoners of war. Interestingly, when the researchers primed their Christian participants with a text about Muslim culture that contained words that describe uniquely human qualities such as "passion" and "ambitious", they were less likely to later pick out dehumanising word to describe Muslims than those primed with a more neutral text. They were also less likely to endorse the use of torture.

So, the more you hear a group described in a dehumanised way, the more likely you are to dehumanise them yourself. This leads to a reciprocal, vicious cycle. But it may also depend a little on your own personal background.

"People who are higher in social dominance, or look at social hierarchy between groups as desirable, tend to be more likely to dehumanise," says Nour Kteily, co-director of the Dispute Resolution Research Center at Northwestern University in Illinois in the US. In the context of violence, groups who often feel dehumanised then dehumanise in kind, he says. "We're starting to see we often assume or have perceptions about how dehumanised we are."

He points to a study that asked participants to rate someone on a scale of 0-100 in terms of how evolved they thought someone was, in the context of a famous images depicting "the ascent of man". It found that Democrats and Republicans thought their rivals would rate them as 60 points below being considered fully human, whereas they actually placed them at 20-30 points below being fully human. They had correctly identified they were being dehumanised – but they were grossly overestimating how much they were being dehumanised.

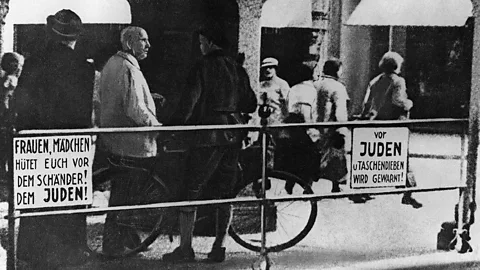

But Enock has found it important to look beyond just the use of dehumanising language in terms of causing harm. In an analysis of anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda, she found that highly offensive humanising terms were used up to three times more than dehumanising terms. "When we take this into account, maybe it's not just the dehumanising comparisons leading to mass violence, but the idea they're bad humans and morally deserving of the harm inflicted on them," she says.

There are also plenty of examples in which we have harmed humans, and that we have cared for animals, she points out. Being a human or being an animal essentially doesn't determine whether you're protected or hurt. "There isn't really any evidence to suggest that humans have this natural care and empathy for one another," says Enock. "Actually, people are harmed when perpetrators are fully aware of their humanity."

This might appear to be a contradiction, but there is something more subtle at work.

De Ruiter's analysis of the Primo Levi memoirs showed how a group of people could be simultaneously dehumanised and humanised. "Scholars have noted that it is often said that mass atrocities, such as massacres and genocide, can only take place once the victims have first been dehumanised," she says. "Yet, a closer look at how alleged perpetrators of dehumanisation factually treat their victims reveals that the former do not always seem to regard the latter as fully less than human." For her, dehumanisation needs to be understood as something much broader than animalistic name-calling or objectifying. It's philosophically a wider blindness to the fact that someone may be a human being with subjective experiences. It is far beyond just language; it is "a fundamental moral misrecognition".

Enock agrees. Her study using fictional political groups also asked participants to rate them on a series of traits. Those who described a group with animalistic slurs, tended to view that group as having fewer positive traits rather than less humanness. Their humanness was not changed at all; it was their social desirability and moral character.

Emma Briant, associate professor in news and political communication at Monash University, in Melbourne, Australia, has identified this in the language being used in the current violence in Israel and Gaza. "I think an important feature this is combined with, in the rhetoric enabling civilians to be dehumanised and killed by both Hamas and Israel, are claims that civilians are not really civilians," she says. "Both have made this claim. Hamas did so on Al Jazeera, claiming settlers on occupied territories are not really civilians. Israel has repeatedly conflated Palestinian people with Hamas. In propaganda, often the creation of 'us' and 'them' camps based on core values precedes dehumanisation rhetoric, so we are already predisposed to an ideology of exclusion and distrust."

Studying the effect of dehumanising language has an impact for everybody. Practically every element of one's identity that can be considered part of a specific group of people appears vulnerable to it. It happens with immigration – one study found that comparisons of immigrants to vermin or disease led to more negative immigration attitudes. A later study from the US in 2023 found via a survey that those who exhibited racial prejudice towards Latinos could be encouraged to support for-profit immigrant detention centres if dehumanising language was deployed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is also seen with gender. Studies have revealed that a focus on women's sexual features or functions leads to them being animalistically dehumanised, and that comparing women to animalistic predators can make someone more likely to agree with hostile sexist attitudes than if they're described through animalistic "prey" metaphors.

But there may also be ways to stop people from dehumanising each other, they believe it is doable. Encouraging positive contact experiences between different groups of people is one solution. Another is humanising narratives. "Are there similar amounts of human-interest stories on either side?" says Kteily. "We knew humanisation is associated with empathy. When you hear tragedy, that is associated with feeling more empathy. When you talk about deaths or killings as statistics, that's much less likely to promote empathy."

He adds that when it comes to short-circuiting a conflict in particular, he has been interested to hear stories of people refusing to let their own pain and anguish be used to feed further violence. "There are people whose own family members have been taken hostage, who don't want to recreate the same suffering on the other side," he says. "Expressing concern for the humanity of all even when you yourself have dealt with immense suffering, is to see others as human."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.