The shocking truth behind historic anatomical art

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Mauritshuis, The HagueFor centuries, real dead bodies inspired scientific illustrators and great artists alike in the creation of intricate and beautiful artworks. But the stories behind these cadavers – and how they were acquired – are dark and grisly, as a new exhibition reveals.

His body is like sculpted grey marble, each muscle flawlessly contoured. But the luminous figure in Rembrandt's painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1632) is no hero from Greek antiquity. He is an executed criminal being dissected in a theatre. His crime? Stealing a winter coat.

Warning: This article contains images and details that some readers may find upsetting

Spanning five centuries, the deceased in the anatomical prints currently on show in the exhibition Beneath the Sheets: Anatomy, Art and Power, at Thackray Museum of Medicine in the UK city of Leeds, are also meticulously rendered. These largely anonymous figures, exposed in the most visceral way, illustrated medical atlases that were once consulted by doctors and anatomists or displayed like trophies by wealthy collectors. And like Adriaan Adriaanszoon, the petty thief painted by Rembrandt, none of them consented to images of their unclothed, mutilated bodies being bound up in a book or displayed on a wall.

Mark Newton Photography

Mark Newton Photography"Beneath the Sheets challenges visitors to question whose bodies feature in anatomical textbooks, who was drawing them, and why," Jamie Taylor, the museum’s director of collections, learning and programming tells the BBC. "The bodies depicted in these pages belong to people who throughout history have been repressed, whose rights have been considered secondary, negligible, or ignored."

An anatomy book without drawings is "no better than a book of geography without its maps", declared 18th-Century surgeon and anatomical illustrator John Bell. His intricate, cross-hatched engravings disseminated a detailed knowledge of the body that few had seen outside an anatomy theatre. But a closer look at such illustrations uncovers not just our changing understanding of the human body but also the cultural context in which these images were created.

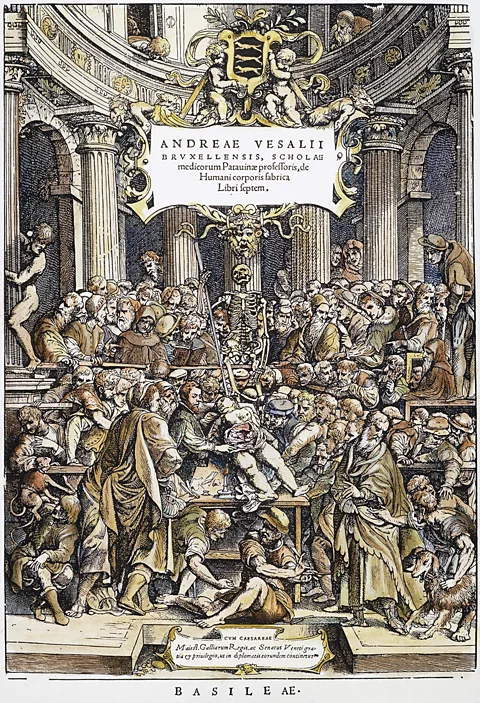

Particularly revealing, and shown early on in the exhibition, is the elaborate title page of Andreas Vesalius's book De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543), the first major text to show human anatomy drawn directly from dissected bodies. In a crowded anatomy theatre, the author, ever the showman, performs a dissection on an executed sex worker − his scalpel revealing to a predominantly male audience if the woman was pregnant, as she had professed in her plea for clemency.

Alamy

AlamyThe difference in social standing and power between surgeon and subject could hardly be starker, and the market for these intricately illustrated books was, the exhibition notes, "at the opposite end of the economic spectrum to the people depicted within their pages".

Medical books became especially lavish when developments in lithography in the 19th Century flooded their pages with vivid colour. The museum's edition of JM Bourgery's sumptuously illustrated Complete Atlas of Human Anatomy and Surgery (1866) has barely been touched, Dr Jack Gann, the exhibition's curator, tells the BBC. Those who could afford such works, he says, "would have displayed them in their homes along with their art collections".

Sometimes the cadaver itself became an object of art for display. The lack of agency many women had over what happened to their bodies after death, and the sinister role that some respected medical practitioners played in this, is exemplified in the case of Mary Billion. She died in 1775 and was embalmed by her dentist husband Martin van Butchell, assisted by the esteemed London surgeon William Hunter, his former teacher and the author of an illustrated book of pregnant bodies lauded for its unprecedented realism. Hoping to lure new clients, Van Butchell dressed Billion in her wedding gown and exhibited her in the window of his Mayfair dental practice and home until his second wife insisted the body be moved to a museum.

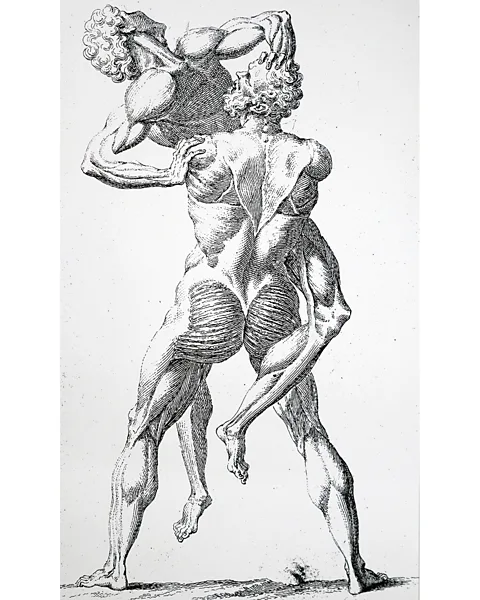

Art and anatomical science have a long kinship. In Renaissance Italy, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo made studies of dissected bodies in mortuaries to help them make the figures in their paintings more realistic, while early anatomical atlases depicted bodies in stylised poses reminiscent of Classical sculpture. William Cheselden's The Anatomy of the Human Body (1741), for example, includes two skinless figures wrestling like Hercules and Antaeus.

Alamy

AlamyFor scientists and artists alike, the biggest challenge was access to bodies, exacerbated by the 1823 Judgement of Death Act, which reduced the number of crimes punishable by death. A lucrative black market for cadavers emerged, with bodysnatchers, nicknamed "resurrection men", stealing corpses from fresh graves and selling them to medical schools for princely sums.

To thwart them, those who could afford to buried their loved ones in cages known as "mortsafes", or had heavy stones laid over their burial site. For convicted criminals and the poor, resting in peace was more uncertain. Relatives of the highwayman John Worthington, executed in 1815, took the extraordinary step of dousing his body in acid to ensure it was unfit for dissection.

Notorious serial killers

William Hare and William Burke became Scotland's most notorious serial killers. They looked to the living rather than the dead, conducting a 10-month murder campaign between 1827 and 1828 in order to supply the Edinburgh anatomy school of Dr Robert Knox with corpses. Mary Paterson, a former inmate of an asylum for "fallen" women, whose dead body was suspiciously warm on arrival, was intoxicated with whisky by her assailants before being preserved in it for three months by Knox.

George Orton

George OrtonThe law eventually caught up with her killers. Though Hare was freed in return for evidence, his accomplice was less fortunate. Lord Justice-Clerk David Boyle sentenced him to death by hanging, and pronounced that Burke, like his victims, be "publicly dissected and anatomised". His skeleton now hangs in the University of Edinburgh's Anatomical Museum.

At the Thackray Museum of Medicine, Paterson's body is also on display, but as a drawing – the ethics of which were vigorously debated by the curatorial team. She's drawn like Velázquez's Rokeby Venus, points out Gann. "It is a very sensual image", but it is also, he says, "the dead body of a murder victim who has continued to be exploited".

Idealised physiques dominate these medical books, blurring the boundaries between science, art and erotica, and offering insights into the preferences and preoccupations of their creators. In one of Nicolas Henri Jacob's most haptic illustrations for Bourgery, scientific detachment is called into question as two pairs of disembodied male hands probe the dissected breast of a young woman whose hair has been styled like an Ancient Greek beauty.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

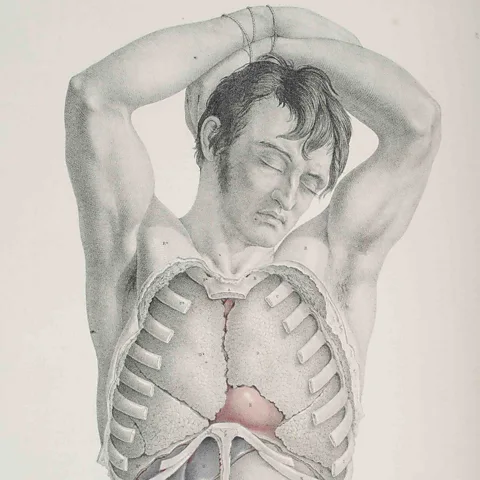

Mauritshuis, The Hague"Anatomical illustrations gave off heat, provided pleasure to the men who produced, gazed upon, and studied them," argues Michael Sappol in Queer Anatomies (2024). For surgeon and artist Joseph Maclise, that "gaze" was queer, contends Sappol. Maclise's landmark work Surgical Anatomy (1851) is dominated by men in ambiguous poses: their muscular arms raised submissively behind their head, for example, or their mouth parted in a way that could be read as pleasure. It's possible, proposes Sappol in a 2021 essay, "that Maclise's renderings, in some queer and occluded fashion – maybe not even fully apparent to Maclise himself… were a space in which he unveiled himself, sent out flares of homoerotic desire".

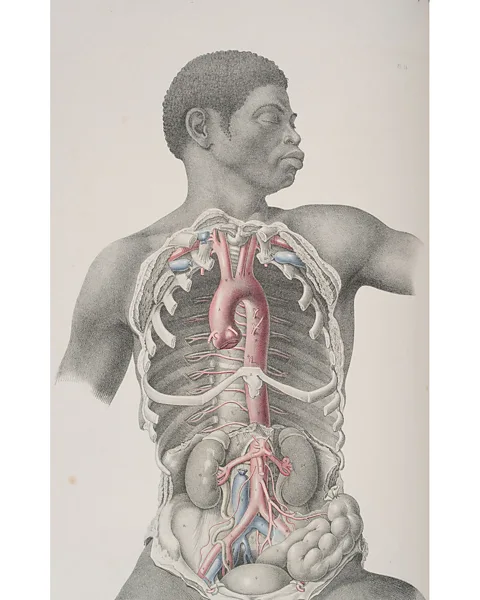

"People perceive that an anatomical illustration is an objective depiction of the human body to the best of the artist’s abilities," says Gann, which is something that the exhibition seeks to "break apart". "In truth, they are subject to culture and tastes and artistic movements as any other form of art and illustration." A nameless black figure in Maclise's book, thought to be the only black body in anatomical works of the period, is a case in point, having been removed from the edition created for pre-abolition America.

His depiction, notes Keren Rosa Hammerschlag in her 2021 essay, Black Apollo: Aesthetics, Dissection, and Race in Joseph Maclise's Surgical Anatomy, is "notably aestheticised, placing him in dialogue with classical statues such as the Apollo Belvedere, the "high" art productions of Joseph’s brother Daniel Maclise, pictures of black pugilists, and abolitionist imagery from the period."

Mark Newton Photography

Mark Newton PhotographyWithin a decade of Maclise, Henry Gray's celebrated Gray's Anatomy, illustrated by Henry Vandyke Carter, would finally place an affordable resource in the hands of medical students, yet it too was indebted to unclaimed bodies from workhouses and infirmaries. "There is a silence at the centre of Gray's, as indeed there is in all anatomy books, which relates to the unutterable," writes Ruth Richardson in The Making of Mr Gray's Anatomy. "As mass-produced images, [the bodies of these people] have entered the brains of generations of the living... And nowhere but in Carter's images do they receive memorial."

The use of voiceless victims to further medical science endured into the 20th Century. Eduard Pernkopf's Atlas of Topographical and Applied Human Anatomy (1937), for example, still used by some surgeons today, features prisoners of war dissected by Nazi doctors working under Hitler's regime.

Sixty years later, on the eve of the millennium, a digital archive of the entire human body, created by The Visible Human Project, was published in The New Atlas of Human Anatomy by Thomas McCracken. The 3D images were formed from hundreds of one-millimetre slices of the body of Joseph Paul Jernigan, a Texan murderer executed by lethal injection in 1993. Though he had agreed to donate his body to medical science, he could never have foreseen such a visible future for it. "This is an enormous dataset still available for people to use today," says Gann, who concludes the exhibition with the question: "How far have we really come?"

Beneath the Sheets: Anatomy, Art and Power is at the Thackray Museum of Medicine, Leeds, UK, from 7 February to 21 June.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.