Why planting a tree is a radical act

Alamy

AlamyA 1980s green project by the German artist Joseph Beuys has inspired a contemporary art duo. Bel Jacobs speaks to them about activism, hope, regeneration – and the power of nature.

In 1982, artist, environmental activist and German Green Party founder Joseph Beuys began what was arguably his most seminal work: the planting of 7,000 oak trees around a city in central Germany. Beuys conceived 7000 Eichen (or Oaks) as a way of re-connecting the traumatised citizens of Kassel – which had been heavily bombed in World War Two – with their natural environment, and to offer them alternatives to the societal structures that had taken them into war in the first place. As each tree was planted, it was paired with a pillar of basalt – the inky black, iron-rich rock formed in the cooling of a volcanic disruption – taken from a pile that Beuys' had arranged messily on a neoclassical lawn in front of the city's public Museum Fridericianum.

More like this:

- Why do we need to find wilderness

"It was the equivalent of dumping 7,000 rocks in the middle of Trafalgar Square," smiles Michael Raymond, assistant curator of London's Tate. "Initially, the people of Kassel hated this. It reminded them of the bomb sites they had witnessed over the past decade. But Beuys was challenging them. He was saying to them: if we find places to plant the 7,000 trees, we'll remove this blight upon the town centre." Residents, alongside city planners, gardeners and environmentalists, helped to pick locations for the saplings, and to plant them. Areas slated to become car parks suddenly became homes to young trees and communal spaces. "So many people now are hugely appreciative of these trees and the green space they provide," reflects Raymond.

Alamy

AlamyAs the world emerges from 16 months of fear and uncertainty caused by a global pandemic, many of us share that appreciation quite viscerally. During repeated lockdowns, the ability to "escape", even for an hour, into nearby parkland has redrawn our relationships with the planet's ecology. We have become more aware, both of nature's extreme beauty and of its fragility; qualities that Beuys – provocative and visionary – sought to amplify during a career now widely regarded as a forerunner to some of society's most progressive ideas for change. "To discover Beuys is like finding a spring," says Fabio Maria Montagnino, author of the paper, Joseph Beuys' Rediscovery of Man-Nature Relationship. "You find so many ideas about what we should be doing. His was a very complex personality."

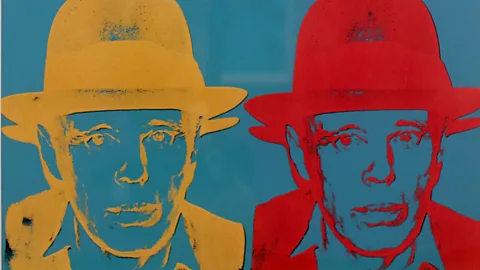

On the centenary of his birth, Beuys remains "seminal", says Raymond. "Through his fusion of politics, art, activism, Beuys is a titan of 20th-Century art." It took Beuys a while to get to his oaks, though. The artist's connection to the natural world was shaped by his belief in its redemptive qualities; the journey to creating what he did in Kassel encompassed seismic philosophical shifts in how best to put that forward. Anyone expecting ethereal landscape paintings will be thwarted. Beuys' art could be robust, disorientating, and viscerally challenging. After a stint with the Luftwaffe, and a battle with depression, Beuys studied monumental sculpture at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art, where he was later appointed professor. During the 1960s, he became affiliated with Fluxus, a network of artists including Yoko Ono who challenged traditional boundaries between art and life, exploring ideas of transformation through film, painting and performance.

Alamy

AlamyBeuys revelled in the concepts but took them further, positing that art was political, that everyone was essentially an artist and that we all had to work together to create a more just, humane and ecologically sustainable future. His vision was sorely needed. In West Germany, the impact of heavy postwar industrialisation was becoming all too clear. Beuys founded the Free International University, embedding at its heart the concept of social sculpture or art as communal interventions. Between June 24 and 1 October 1977, during an art event titled 100 Days of Free International University, Beuys demonstrated the university's workings and potential through a series of workshops, panels, artistic performances and installations, centred around global issues and challenges.Pictures from the event show Beuys's small figure, in his trademark felt hat, sitting among a group of rapt faces.

The Free International University continued as an organisation for several years, and has been influential. And yet, for all that, 7,000 Eichen (7,000 Oaks) was probably the project's most vital expression. Of the artwork, Beuys told Scottish gallery owner Richard Demarco: "I wish to go more and more outside to be among the problems of nature and problems of human beings in their working places. This will be therapy for all of the problems we are standing before." After all, what inspires a reconnection with – and a love for – the natural world, more than asking a traumatised people to put their hands in the earth, around the roots of a young tree? Pieter Heijnen, a former student of Beuys, recalls being present with Beuys during a planting. "Once the tree grows tall, the planter will be long gone," he reports hearing the artist say, wistfully. "Imagine how many birds will flock to Kassel, once these trees are here. The planting of these 7,000 trees is all about sculpture. It is the absence of originality. Once the tree has established itself, it's just nature. A tree full of chirping birds with the wind blowing through it… music! This is Sculpture that reaches far into the future."

Tree of life

The artist's love for the trees is palpable. Now, Beuys's concept of nature as regenerative and as trans-generational appears currently in London, in the form of Beuys' Acorns, a project which features 100 young saplings, grown from acorns collected from the German city by Ackroyd & Harvey, aka the British art duo Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey. They are known for work that – Beuys-like – sits at the intersections between art and activism, biology and ecology, architecture and history.

Tate Modern

Tate ModernStanding in rows on the Tate Modern's south terrace, this is the latest incarnation of an ongoing project – the ever-growing saplings have been exhibited in different locations since 2009 and are just high enough to create a delicate forest of their own. Still, "protective" is the key emotional feedback that Raymond has received towards the display from those who have seen their saplings around the world? Ackroyd agrees: "I often say, I've never cut the umbilical cord with these trees. It's working with living material." And it is living material that is currently under threat. According to Global Forest Watch, 2020 was the third worst year for tree loss since 2002, when monitoring began. Just three percent of the world's land remains ecologically intact and with healthy populations of all its original animals and an undisturbed habitat. We are almost out of time, as Beuys argued, to turn our love for nature into something more pro-active.

"I keep thinking about what Beuys would say, if he were to step back and see where we are," muses Ackroyd. "Because it's nothing short of devastating. We are living the tragedy [that was] unfurling when he was alive. He could see it. It was the beginning of more political and social conversations but the corporatisation, the commodification, the consumerism: they've all just ramped up. We have to get back to respect for the natural world and to realise that we are a part of it." In a heartstopping memento mori, the trees' terrace lies above the Tate's Tanks, three old circular underground oil containers forming the building's basement which have been converted into gallery spaces; in one of them sits Beuys' own artwork The End of the Twentieth Century, broodingly: 31 rough-hewn basalt blocks, four of which hark from the infamous pile on Friedrichsplatz.

Tate Modern

Tate Modern"It's a beautiful synergy," says Harvey, enthusiastically. "Because, of course, oil is only possible through the fact that plants photosynthesise." But it's the contrast that galvanises the Tate's Raymond. "The tank space feels like going down into the catacombs; the blocks have this coffin-like, melancholy gravitas. But the trees above really feel like they're sprouting out life. It's a happier environment." And that, at last, is what trees – all trees – can offer: better times. "I have a huge need right now to dedicate myself in a much more singular fashion to Beuys' Acorns, and to how we start to bring the trees into their final growing," says Ackroyd. The next phase starts now. "Between now and 2025, we're looking to get as many of the trees into the ground as possible."

The hope is that the trees will form part of an exquisite – and genuinely restorative – "mosaic of habitats" which is deeply embedded in the characteristics, the needs and the wildlife of the local community. "Each tree will need to hold a conversation with the ecology of place and the nature of place and people of place as well, to create a sense of deeper care and respect and love for the nature that is around us." Seven of the saplings will be permanently planted around the Tate Modern next year. Each exhibition of Beuys’ Acorns has included a series of public "conversations" with invited guests from the fields of science, literature, law, art, architecture, politics and economics. The Tate Modern will be no different, with poet and writer Ben Okri takingpart in a multi-day project with a performative element around the saplings. "It will be a type of arborial salon,” says Ackroyd, happily.

Tate Modern

Tate ModernThoughts from the conversations would then be printed on one of Ackroyd & Harvey's grass coats from 2019. Beuys would have recognised the impulse immediately, as he would have recognised the need to centre the natural world – and art as its amplifier – at the heart of almost every human activity. "The trees are a message of hope," says Raymond. "We have it in our hands to make positive changes, and that's hopefully something people take away from the display. I'd be thrilled to learn that some people had come along and thought: 'I'm going to go and plant a tree. That's something I can do. I'd like people to take time to appreciate that as a radical act – and also appreciate just how beautiful these trees are."

Beuys' Acorns is at Tate Modern, London, until 14 November.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.