The rise and fall of fashion’s greatest innovator

The pioneering visionary Paul Poiret has been less celebrated than other designers, but ultimately he is the most significant of them all, says Cath Pound.

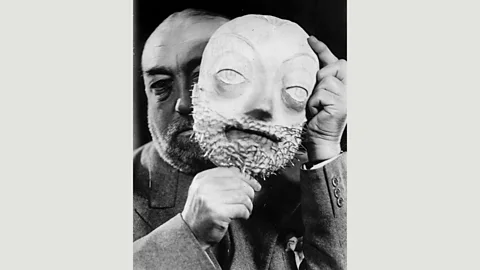

Paul Poiret was an unparalleled innovator in the world of fashion. He liberated women from the corset, draping them in exquisite, oriental-inspired creations, invented the concept of the catwalk and, much to the chagrin of Coco Chanel, was the first French couturier to launch his own perfume.

Hollandse Hoogte/Rogier Viollet, Paris

Hollandse Hoogte/Rogier Viollet, ParisUniquely skilled in marketing, he was also the first designer to realise that fashion could be promoted as a lifestyle that branches into home furnishings and accessories. He created sumptuous designs to compliment his luxurious couture creations.

According to a new exhibition at The Hague’s Gemeentemuseum, this desire to create a total artwork meant that Poiret’s influence extended far beyond the realms of fashion. In surrounding himself with artists, designers and architects who could help develop and promote his work, he invented a unique visual style which would prove to be the seed bed of an entire artistic movement.

For the Gemeentemuseum’s director, Benno Tempel, Poiret was in fact nothing less than “the father of Art Deco.”

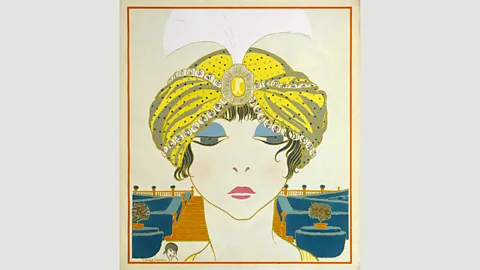

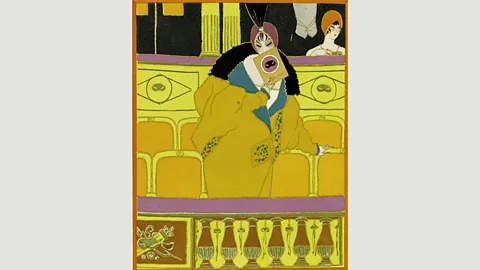

Georges Lepape

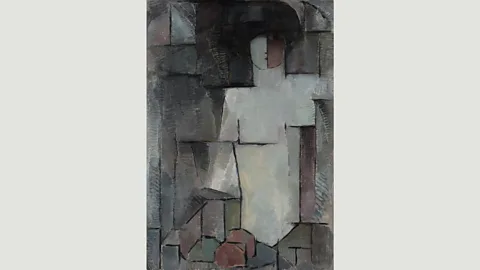

Georges LepapeWhat we now think of as Art Deco took its name from the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs held in Paris in 1925. Despite being the ultimate bourgeois art movement, with its emphasis on exotic and luxurious materials, it was actually an amalgamation of many different avant-garde styles. It incorporated the fragmented images of French Cubism, the angular, diagonal lines of Russian Constructivism and the fascination with speed and modernism that came with Italian Futurism.

It was while researching previous exhibitions on Art Deco that Tempel came to realise “Poiret was always the person that everything was turning around, like the spider in the web.” He sees him as the art world’s equivalent of David Bowie, a man who saw everything that was going on around him and mixed it all together. “He had a nose for the spirit of the times.”

After brief spells at Doucet and Worth, Poiret founded his own house in 1904 and, with his wife and muse Denise beside him, set about revolutionising the world of fashion with his focus on bold, bright colours and flamboyant designs inspired by the book, Arabian Nights, and the costumes of the Ballets Russes.

Victoria & Albert Museum

Victoria & Albert MuseumHaving long considered himself on a par with artists – “It seems to me we practice the same craft,” he declared in his autobiography – Poiret soon began receiving them at his home in order to “create around me a movement.” His circle included Constantin Brancusi, Kees van Dongen, Robert Delauney, André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Paul Iribe, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani and Pablo Picasso. It may seem an eclectic mix, but elements of all their work would later be incorporated into Art Deco.

His innovative window displays and extravagant social gatherings, attended by his artist friends and the cream of Paris, society soon brought him notoriety. But it was his decision to give the artist and designer Iribe free reign to illustrate his designs which created his first major impact on the art world. The highly stylised, decorative and colourful images which he conceived with the artist not only perfectly suited Poiret’s fashion line, but also provided Art Deco with the basis for its visual idiom.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of ArtA year later he hired Raoul Dufy to design vignettes for his in-house stationery, and would later launch his career as a textile designer using his fabrics in both his fashion and interior lines.

As well as hiring artists to work for him, Poiret was also a keen patron and promoter, primarily through the Galerie Barbazanges, a commercial gallery within his couture house that he leased while retaining the right to hold a couple of shows there a year. It was here that Picasso first showed his groundbreaking masterpiece Les Demoiselles D’Avignon in 1911.

Gemeentemuseum

GemeentemuseumIt clearly had a major impact on Poiret, for a couple of years later a Vogue article entitled “Dress Plagiarisms from the Art World,” noted Poiret’s “Cubist crêpe” fabric and the “broken silhouettes,” of his designs.

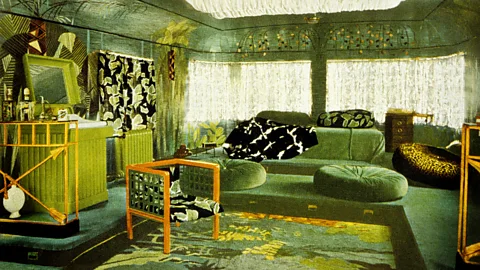

Interior life

Poiret’s move into interior design was heavily influenced by the Austrian Wiener Werkstätte movement that saw architects, artists and designers coming together to produce highly original luxurious furnishings and goods, many of which featured characteristics of what we would now consider Art Deco.

However, although he admired their work, Poiret likened the Austrian Design schools to “iron corsets,” and feared that their rigid training methods stifled creativity. In much the same way that he had liberated women’s bodies from constriction in his dress designs, he gave students in his own École Martine the freedom to explore their imaginations so that they might produce more natural, unstudied designs. These were then sold in his Maison Martine shops, the first of which opened in 1911.

Hollandse Hoogte/Rogier Viollet

Hollandse Hoogte/Rogier ViolletThe innovative nature of this venture was noted by American Vogue, which commented that “certainly couturiers have never before insisted that chairs, curtains, rugs and wall coverings should be considered in the choosing of a dress.”

A number of private and public commissions for complete interiors, notably the home of actress Isadora Duncan and the interior of Helena Rubinstein’s Parisian beauty salon were evidence of the success of this new venture.

Poiret now dominated the world of fashion, and the personal aesthetic he had helped popularise with his home furnishing lines was gaining such ground throughout Europe that a major exhibition, the original Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, was planned for 1915. But then came war.

Out of favour

It is impossible to predict how the style might have developed had that exhibition gone ahead. As curator Madelief Hohé says, “all the ingredients were there but the transformation to the more stylish elements of the 1920s was not visible yet.” Still, if you look at items from the 1910s, people will say “Oh yes that’s Deco.” She adds.

Nor is it possible to predict how Poiret’s personal fortunes may have differed. The harsh realities of daily life during the war meant that his extravagant designs fell out of favour.

Hollandse Hoogte / Rogier Viollet

Hollandse Hoogte / Rogier ViolletPost war, Poiret enjoyed a brief resurgence amongst those who wanted to put the horrors of 1914-18 behind them and live life to the full. He also maintained his links with the avant-garde, giving Man Ray his first work as a fashion photographer. But gradually his influence began to wane as the sportier, more informal aesthetic of Chanel began to take over.

For the 1925 exhibition he staged a last ditch attempt to hold on to his reputation, launching three specially designed boats on the Seine, each lavishly decked out in Martine designs with his fashions displayed on mannequins featuring heads inspired by Modigliani. But the effort bankrupted him. Forced to sell his art collections and abandoned by Denise, Poiret slowly sank into poverty and obscurity, as the movement he had played a pivotal role in creating flourished around him.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of ArtIn fashion, sadly, “he had found a style he loved and he didn’t move with the times,” says Hohé. A telling anecdote has Poiret coming across Chanel attired in the little black dress which she was to make iconic. “For whom are you in mourning?” he was alleged to have asked. “For you, Monsieur,” came the acid reply.

It may be Coco Chanel whose influence dominated fashion in the coming decades but as Tempel says, “she never created an art movement.” That honour fell exclusively to Poiret.

To comment on and see more stories from BBC Designed, you can follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. You can also see more stories from BBC Culture on Facebook and Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.