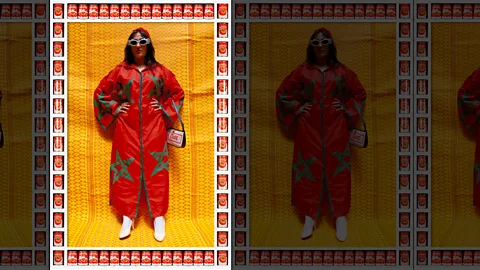

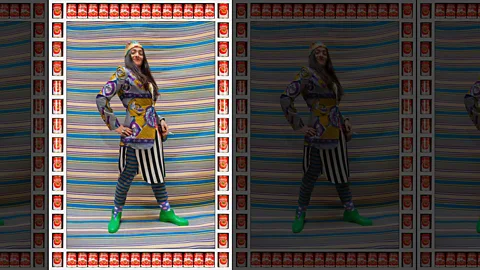

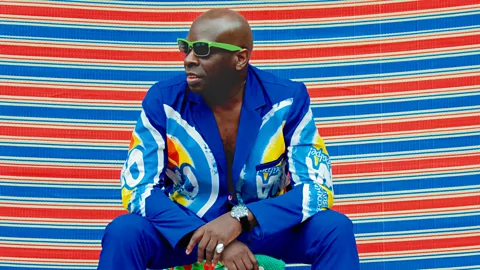

Hassan Hajjaj’s vibrant photographs are a riot of colour

La Caravane is a new exhibition of Hassan Hajjaj’s photography at London's Somerset House, that includes works from his 20-year career. Javier Hirschfeld meets the artist.

Born in 1961 in Larache, Morocco, Hassan Hajjaj moved to London with his family when he was 13. Leaving school at 15, he found himself at the centre of the capital’s legendary 1980s club scene. He turned his attention to design and began to work with artists, musicians and DJs, organising underground parties and launching a fashion label. Hajjaj has created a brightly colourful and personal visual universe inspired by both his London life and his childhood memories.

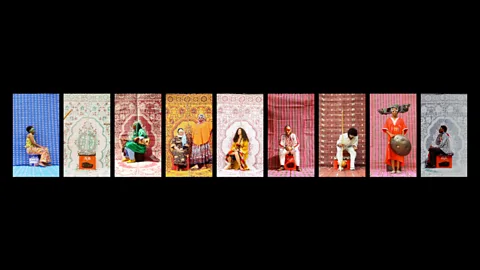

Hajjaj drew inspiration from the traditional photography studios families would visit in 1960s Morocco, from visually stunning Indian film posters, and from the fashion and abstract photographers he found in London. “It was really just a labour of love… it wasn’t something I was planning to use for work or to become an artist. I took pictures of my friends, my cousins and a couple of characters I found interesting. I wasn’t shooting regularly, it was now and then, and then the passion of it just took over."

Hajjaj saw an opportunity to bring together two very different cultures through his images. “In the 70s when I came to London and said I came from Morocco they always made fun and said ‘ah Sahara sand, hashish, mint tea...’” he reveals. “I wanted to try to show that we have a culture that has a difference, that there’s a lot of depth, that there’s stuff beneath the caricature of the countries."

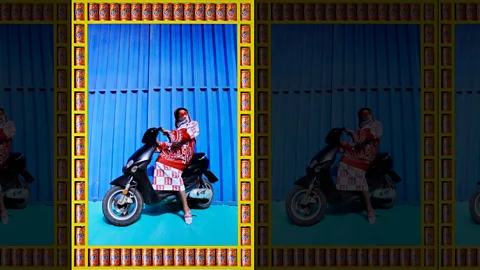

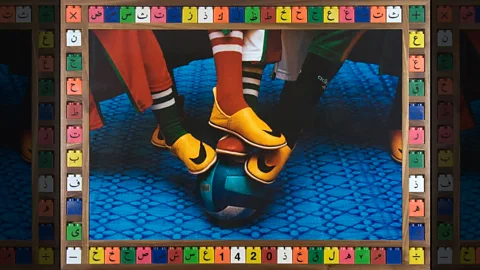

The first body of work Hajjaj exhibited focused on Arabic products, combining them in his images with Western brands like Fanta, Coca Cola, Louis Vuitton and Nike. “It was about showing graphics from the Arab world that I got influenced by, graffiti artists, graphic designers,” he says. “In Arab countries there’s going to be brands from the West that are written in Arabic, but you would immediately recognise if it’s Coca Cola or Pepsi. So I played on this to take people on a journey to local products.”

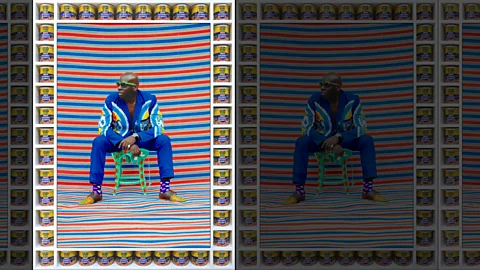

Hajjaj’s work is now collected by institutions such as the Victoria and Albert and British museums as well as proving hugely popular online. “My early shows were different - I’m talking almost 20 years ago - being under the banner of ‘Arab artist’ or ‘Muslim artist’… I felt I was on my own in a way,” Hajjaj explains. “I had this new audience, very positive, lots of things going viral on the internet. And it made me realise that prior to that, I had really strong support from my culture, right across the Middle East, even the Arab kids that lived in Europe, because the internet helped to expose my work. I realised from emails I got that I was doing something positive for the culture.”

“I was very happy because it's almost as if I got a tick from my background. I would have been very sad if I got success in America and nobody in my culture had known my work.”

"Kesh is short for Marrakech." The city of Marrakech inspired Hajjaj’s project Kesh Angels, “because it is a city full of bikes, probably like Rome, because of the architecture of the city,” he says. “It´s probably the only city in Morocco that's actually using bikes and everybody uses them, from young, old, male, female, traditional, modern. I took this idea that was happening there and highlighted it and added my fingerprints,” Hajjaj says, who started work on the project in 1997. “Luckily they were friends, and it was about trust. So there are some images that are 100 per cent what they are wearing, I might add some glasses or some socks or something and then I try to set up and get them to pose… it's about people.”

Through the use of beauty, colour and irony, Hajjaj creates works that start conversations about gender, politics, economy or migration. He recalls how some of his images were perceived differently after the 9/11 attacks. “It was a sensitive moment. Even for me there were moments of worry about how people would perceive my images. In 2007 I put up a big image of a woman with the veil. I put it up and the next morning I went to Morocco for a month and I thought, ‘when I come back it will be sprayed by people saying some negative stuff’, and then I came back and I saw people taking pictures with it, so it was totally the opposite of what I expected. But there was a definitely a period of time when I was worried [about] the work and I didn’t want to show,” he says.

For Hajjaj, leaving Morocco’s vibrant colours, “was almost like going to black-and-white movies, and somehow in my work I must have gone back subconsciously to where I’m coming from,” he explains. “I always liked black-and-white pictures, I almost preferred it. But colour came naturally when I looked around me for stuff to shoot, in the medina or the souk when I’m in Morocco, or Brick Lane or Portobello in London."

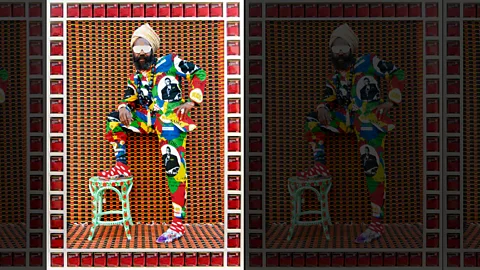

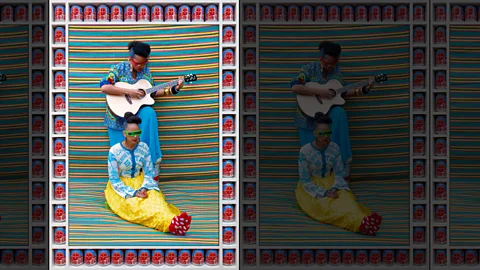

My Rock Stars is Hajjaj’s most recent project, which looks back to his days in 1980s London. “I [had] this ton of people who are underdogs, they are not mainstream, so I thought why not start documenting them, doing it in my style where I am trying to make something out of nothing, trying to have this cheap textile, cheap stuff and make it look grand, something that could be from the past or the future.”

"Growing up in Morocco there’s always music around, but then there was Indian music, Italian [and] Arabic Egyptian, so I had all this influence. Coming to England it was discovering all these new sounds by different people from all parts of the world. I discovered Soul, Reggae, Jazz, Funk. There was music around me all the time. My friends were musicians and I was probably the frustrated musician.”

My Rock Stars Experimental, volume 1 is Hajjaj's first series of video portraits.

Hajjaj’s work follows the tradition of West African studio photography. "When I started doing the studio shoots, obviously, I had in mind Malick Sidibé, Samuel Fosso… they were the photographers of the city. I realised those photographers documented those cities at that point of time. Then I thought to myself, ‘I am somebody from this city but I’ve been moved to the UK and all these friends of mine are also being moved like myself’. That's why I call it ‘documenting’ because it's that moment of me being with them and also who they are because they have inspired me, influenced me in my work as well as my life.”

Although Hajjaj had been consistently shooting portraits for five years (mainly for himself), he was uncertain about showing his portraits to the public. “I showed my first body of work with all the products in 1993, and then I did my first shows in the late 90s. But then when I started taking pictures of friends I thought it was more personal, I just didn’t want to show it anywhere. So I felt I had to protect it for some reason. I didn’t know why,” he says. It was after showing those portraits to curator Rose Issa that they decided to do a show in 2007.

Rose Issa loved the work and asked him to print one of them to show to a client. Hassan printed two, framing one in a traditional way, leaving himself the other to experiment with: “I thought ‘I am still young enough to have fun with it, to look for products, to communicate with people,’” he says. “I started playing with that notion, because I was already using products within my pictures. The idea was, using this to attract people without realising that I am using the repeated patterns that we have in Morocco. All that came out that [ended up] giving a style, easy to read from young kids to somebody older.”

"When you see Malick Sidibé you see a time, you see the 1950s or 60s. In my pictures I want to confuse people because it could be the past… there’s no date on them in a kind of way. The idea is documenting these friends who had been scattered around along the globe like myself. Malick Sidibé had his journey and hopefully I’m having my journey in my own way."