Did American Psycho predict the future?

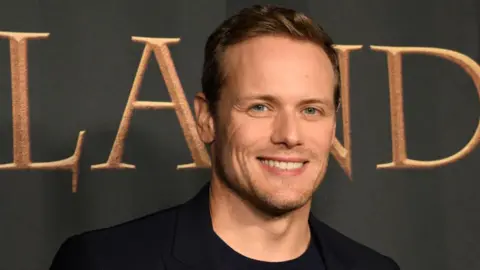

Lionsgate

LionsgateAs a musical version of Brett Easton Ellis’ novel opens on Broadway, Nicholas Barber looks at how the book – and its offshoots – prefigured the way we live now.

If you’ve ever had a hankering to see a jaunty Broadway show about someone who hires prostitutes so that he can lop off their limbs with a chainsaw, then you’re in luck: a musical based on Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho is previewing in New York in March.

It’s not the craziest subject for an evening of toe-tapping entertainment: the title characters in Sweeney Todd and The Phantom of the Opera are both serial killers, after all. But when Ellis’s novel was published in 1991, nobody would have believed that such a controversially gruesome book would one day be the source of a Tony contender. A virtuosic commentary on conspicuous consumption in the 1980s, American Psycho is a darkly funny first-person account of an investment banker’s decadent lifestyle, which ranges from cocaine-fuelled nights out at Manhattan’s most expensive restaurants to the murders he describes in similarly minute detail.

Its detractors loathed it, and even its fans would agree that its anti-hero, Patrick Bateman, is one of the most unsavoury creations in literary history. So what does it say about us that we’re now willing to whistle along to his depravity? Have we inched closer to Bateman’s way of thinking over the past 25 years? Or has the story told in Ellis’s novel been diluted with each subsequent retelling? The answer is somewhere in between.

Looking back, it’s quite touching to recall that in the early 1990s, something as highbrow as a novel – rather than a video game, a rap album or an ill-considered tweet – could have prompted such outrage, but American Psycho was headline news. Completed when Ellis (like Bateman) was just 26, it was condemned as misogynistic pornography by feminist authors, Gloria Steinem and Kate Millett included.

The New York Times slammed it as “moronic and sadistic”. The National Organization of Women campaigned for a boycott. And its publishers, Simon & Schuster, were so agitated that they cancelled their deal with Ellis. “It was an error of judgement to put our name on a book of such questionable taste,” said the company’s CEO, Richard E Snyder – because if there is one thing that literature should always be, it’s unquestionably tasteful. American Psycho was then published by Vintage Books, but the storm of disapproval didn’t die down. Many shops refused to stock it, and, in Australia and New Zealand, the novel couldn’t be sold to anyone younger than 18. Even then, it was shrink-wrapped to ensure that under-age browsers wouldn’t be corrupted.

Alamy/Lionsgate

Alamy/LionsgateIrvine Welsh, the author of Trainspotting, said last year that the “negative reviews the novel received now sound a little like the stampeding of frightened children”, and it’s true that some of the book’s most vociferous opponents seem to have made a point of misreading it. One feminist campaigner labelled American Psycho a “how-to novel on the torture and dismemberment of women”, but the violence (which is inflicted on men as well as women) doesn’t start until a third of the way through, and when it does, there is some ambiguity as to whether it actually happens, or whether it all takes place in Bateman’s fevered imagination. Still, the protests were a testament to how powerfully vivid the novel can be. And they were, ultimately, invaluable publicity. American Psycho was soon so famous – or infamous – that a Hollywood movie was inevitable. But how could any film visualise Bateman’s macabre hobby without being unbearably horrific?

Left to the imagination?

Step forward Mary Harron, who had directed 1996’s I Shot Andy Warhol. Harron and her co-writer, Guinevere Turner, knew that in order to translate Ellis’s stomach-turning prose into something that audiences could watch without being sick into their popcorn, they had to emphasise that American Psycho was a comedy, and that Bateman himself was the butt of the joke. In their 2000 film, it’s plain that he isn’t a ‘master of the universe’ in the mould of Wall Street’s Gordon Gekko. He is, Harron has said, an “absurd, ludicrous, pathetic monster”.

When he tries to get a reservation in an exclusive restaurant, the maitre d’ bursts out laughing. Among his colleagues, he doesn’t have the swankiest apartment or even the swankiest business card. His work consists of lounging in an office watching quiz shows and doing the crossword, and he only got that job via his family connections. In general, Harron and Turner have no time for the machismo and hedonism celebrated by Oliver Stone in Wall Street and Martin Scorsese in The Wolf of Wall Street. And, unlike The Silence of the Lambs, their film doesn’t buy into the fallacy that being a homicidal maniac somehow makes you a charismatic genius. Bateman, as Turner put it, is “a big dork”.

It’s an interpretation which is embraced by the film’s leading man, Christian Bale. Seemingly modelling his performance on Steve Martin’s in The Jerk, Bale may look like a Greek god, but he never lets us forget that Bateman is an anxious doofus who believes that it’s the height of sophistication to be a Phil Collins fan. Incidentally, his sudden switches from smarmy chatterbox to frenzied butcher make Bale’s subsequent casting as Batman seem like a wasted opportunity: he would have been a lot more suitable as the Joker.

Corbis

CorbisAs clever as Harron and Turner’s adaptation of American Psycho is, however, there is no doubt that they blunted the serrated edges of Ellis’s satire. As well as being lighter in tone than the book, the film is less explicit in terms of both sex and violence. And the new musical is less explicit still. A Variety review of the London production which is transferring to Broadway noted its “near total refusal to depict the gore that defines the work”, a decision which “robs the show of darkness and, for the most part, any galvanizing sense of horror”. The people who protested against Ellis’s novel, then, have scored a belated victory: the passages that angered them 25 years ago have been erased.

Staring into the abyss

But if the makers of the film and the show have moved American Psycho towards the mainstream, the mainstream has moved even more rapidly towards American Psycho. For one thing, Bateman’s grisly murders are no longer beyond the pale in popular culture. In the wake of Game of Thrones, the Hannibal TV series, and the various post-Saw torture-porn movies, a far more graphic film of Ellis’s novel could easily be made today. But it isn’t just that our tolerance for blood and guts has increased. In all sorts of ways, Bateman would fit into the 21st Century as comfortably as he fits into his linen suit by Canali Milano, his cotton shirt by Ike Behar, his silk tie by Bill Blass and his cap-toed leather lace-ups from Brooks Brothers.

When the novel was first published, it was seen as an indictment of a materialistic era that had already passed: Harron would later describe her film as a “period thing” that looked back at the excesses of 1980s corporate capitalism from a safe distance. But it’s apparent now that American Psycho is horribly contemporary. Bateman’s exhaustive knowledge of luxury brands no longer seems preposterous: when he chats about designer labels over cocktails with his three best buddies, the book could be a gender-swapped episode of Sex and the City.

Likewise, variations on his sybaritic skincare regime – “a water-activated gel cleanser, then a honey-almond body scrub, and on the face an exfoliating gel scrub” – can now be found in every celebrity magazine. And the byzantine dishes Bateman orders in restaurants – “shad-roe ravioli with apple compote as an appetizer and the meat loaf with chèvre and quail-stock sauce for an entrée” – are indistinguishable from the concoctions served up by the contestants on MasterChef. It’s not just investment bankers who resemble Ellis’s creation these days. It’s all of us.

Corbis

CorbisBut the most disconcerting example of how society has come to endorse Bateman’s attitudes is that, in the novel, he can’t help talking about his hero, Donald Trump. “This obsession has got to stop,” snaps his girlfriend, after the tenth time Bateman has brought up Trump’s parties, Trump’s wife and Trump’s favourite pizza parlour. Somewhere in Manhattan, the American Psycho must be delighted to see what his beloved “Donny” is up to today.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.