Film review: Ex Machina is intelligent but artificial

Universal Pictures International

Universal Pictures InternationalAlex Garland’s directorial debut features a sexy robot and deals with artificial intelligence. But is it a challenging psychological drama or a silly fantasy? Nicholas Barber takes a look.

Step aside, alien invaders. Get to the back of the line, zombies. The figures dominating science-fiction cinema at the moment are machines with artificial intelligence, from the affectionate operating system in Spike Jonze’s Her to the impressionable robot in Neill Blomkamp’s Chappie to the metal megalomaniac in Joss Whedon’s forthcoming Avengers: The Age Of Ultron. The latest film to revolve around such a being is Ex Machina, the directorial debut of novelist-turned-screenwriter Alex Garland, who scripted 28 Days Later and Sunshine for Danny Boyle. A stylish, streamlined psychological thriller, the film has just one main location and three central actors. How many of those actors are playing sentient individuals is its core mystery.

Domhnall Gleeson stars as Caleb, a pale and sensitive young programmer who works for Blue Book, the world’s number one search engine. (The proposition that any search engine could oust Google is probably the most far-fetched idea in the entire film.) One morning a message flashes up on his screen to say that he has been randomly selected to receive a special prize: he gets to spend a week with Blue Book’s enigmatic CEO, Nathan (Oscar Isaac). It’s a jackpot that recalls that old joke: what was the second prize – two weeks? But rather than being appalled by the prospect of hanging out with his employer, Caleb is overjoyed. And he is even more excited when he is flown by helicopter to a remote mountain region, dumped in a meadow, and told to hike the rest of the way to Nathan’s private cabin in the woods.

Needless to say, this is no ordinary cabin, but the entrance to a labyrinthine underground complex with million-dollar paintings on the walls. And its owner is no ordinary tech-company CEO, but a hearty, hard-drinking weightlifter with a crewcut and a bristly beard. As broad as Caleb is skinny, he looks as if he could pick up Bill Gates in one hand, Mark Zuckerberg in the other, and tie them together in a knot. Even more worryingly, he doesn’t have any staff in his inner sanctum apart from one silent assistant (Sonoya Mizuno). The reason for the lack of domestic help, he explains, is that he has been toiling over a top secret project – and now he wants Caleb to be a part of it.

Despite all the time he must have spent in the gym, Nathan has just finished assembling the world’s first conscious android – or so he believes. But it’s up to Caleb to determine whether or not Nathan’s creation is genuinely self-aware. The eager programmer has been brought to his boss’s lair to administer the Turing test, as outlined in the recent biopic of Alan Turing, The Imitation Game: he’ll interview the android, and judge from its answers whether it can think for itself. And so it is that he meets Ava (Alicia Vikander), a winsome, seemingly female humanoid who gazes at him with as much fascination as he gazes at her. Caleb is delighted to be involved in such a world-changing experiment, but as the days wear on, and his conversations with Ava intensify, his thoughts become less scientific. Is the flirtatious robot falling in love with him? And does the unpredictable Nathan have something more sinister in mind?

Computer love

In some ways, the viewer’s doubts about the film will mirror Caleb’s doubts about Ava. Yes, what we’re seeing is superficially sleek, futuristic and clever, but are there any original concepts beneath its lustrous surface, or are we just being hoodwinked by a snazzy mechanical product?

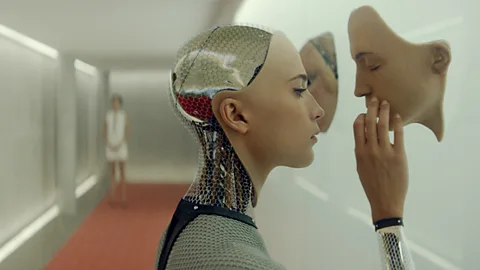

Ex Machina certainly purports to be classier and brainier than the average sci-fi movie about a sexy robot and her Frankenstein-like creator. It has a trio of fine performances from actors who keep bringing new nuances to their characters. It has some crafty twists, and some knowledgeable-sounding scientific dialogue – not surprising perhaps, given Garland’s background as a writer. And the first-time director is no slouch when it comes to visuals, either. Nathan’s minimalist pad may be enviably chic, but it is too orderly and confined to let Caleb to relax in it, while the surrounding mountain scenery (filmed in Norway) is so immaculately gorgeous that you begin to wonder whether it, too, has been fabricated by its billionaire owner. But the centrepiece of the film is Ava. Vikander has been transformed, via a remarkable blend of prosthetic make-up and digital imagery, into one of the most striking robots that cinema has ever envisaged. Some parts of her body are covered in synthetic skin and some in opaque plastic, while others parts have a mesh-like transparent shell, so that we can see the cables and flashing lights inside.

As exquisite as she is, though, it’s tempting to ask why someone would build a robot from those particular materials. And Ava’s design isn’t the only example of Garland prioritising what seems cool over what seems plausible. Once you start peering at the film with a logical eye rather than an admiring one, you don’t have to search hard for plot holes. Why, for instance, would Nathan do all of his research and development singlehandedly? Why is he in the habit of getting blind drunk every night, and then lifting weights with similar zeal the next morning? Why does his house have such an idiosyncratic security system? And why does he insist on Caleb being face-to-face with Ava, when a proper Turing test uses nothing but text communication?

The answer to all of these questions is the same: because the story would fall to pieces otherwise. It’s true that there are certain sneaky motives which aren’t revealed until later on, but even accounting for these last-minute revelations, the bolted-together narrative doesn’t really make sense. Again, you can compare the film as a whole to the character of Ava. Just as she appears to be human when she is actually a machine, Ex Machina appears to be a challenging philosophical drama when it is actually a pulpy, slightly sleazy fantasy. Is it intelligent? Maybe. But is it artificial? Definitely. As elegant as it looks, you can always see the cogs whirring beneath the shiny facade.

★★★☆☆

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.