We all know cheating is bad. So why do we do it?

iStock

iStockCheating at work and sport is unethical, but we sometimes do it anyway. Here's why.

Before this year’s Olympics had even begun, a major scandal sparked headlines around the world – all but one of Russia’s track and field athletes were banned from this year’s Olympics following claims of a state-sanctioned doping programme.

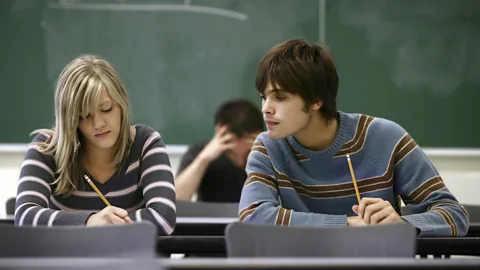

As the Games have progressed, we've heard athletes accusing others of cheating, such as US swimmer Lilly King calling out Russia’s Yulia Efimova, or Australian swimmer Mack Horton accusing Chinese competitor Sun Yang of using banned drugs.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut getting ahead using unethical means isn’t distinct to sport. There are many instances in our work, personal and social lives where the temptation to give ourselves a secret boost may be all too enticing. But it is not only driven by greed, say experts. So why exactly do some people cheat? Is it just that they are morally corrupt or greedy? And does our often competitive society encourage it?

The science of cheating

Psychologists have found that winning can make people more dishonest, while working as part of team can lead to more deceit.

Amos Schurr, a behavioural psychologist at Ben Gurion University in Israel, has been looking into how group behaviour can make cheating seem okay and how winning a competition can make people more likely to be dishonest.

The team behind the research conducted a series of experiments, using trivia, memory and dice games, where they watched how 23 volunteers reported their own winnings. The volunteers could win money depending on, for example, what number dice they rolled. Schurr’s team found that when they had won at a previous memory or trivia game, people were more dishonest, keeping more money than they were entitled to.

Schurr’s team is researching how unethical behaviour may develop after exposure to competitive settings, and how social or group ethics can make people cheat. “We are social creatures – when working in groups, we follow the norms that the group establishes,” says Schurr.

Collaborating in corruption

People cheat when they are encouraged by their peers, according to analysis from the University of Nottingham in the UK, which found cooperation can create ample opportunity for corruption.

iStock

iStockParticipants in the study were asked to work together on a dice-rolling game to win money. The first participant rolled a die, and then reported the number to his or her partner. If the partner rolled the same number, they both got a pay out.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the teams often put their heads together to lie to collect these winnings – the instances of winning double rolls were almost 500% higher than what would be expected if it were assumed the participants were being honest. The research found that the highest levels of corruption in a team occurred when the profits were shared equally and when there were strong bonds in a group.

The study’s authors, Ori Weiseland Shaul Shalvi, concluded that the corruption and immoral conduct at the roots of recent financial scandals “are possibly driven not only by greed, but also by cooperative tendencies and aligned incentives.”

How cheating is changing

The ways people cheat are changing, and this is a significant problem in the world of finance, high levels of company management and politics, according to fraud analysts. Thanks to technology, there are ever-evolving ways for workers and students to cheat.

Phillip Dawson, associate director of the Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning at Deakin University in Victoria, Australia, says: “Some new frontiers for cheating include exam hacking and online tools that manipulate text such as getting away with copy-pasting text by running it through Google Translate from English to Spanish to English.”

The scam is also cropping up in workplaces such as consulting firms that produce international reports, or in media organisations and universities.

iStock

iStockBut Dawson says there are also more ways to get caught, through sites like Turnitin, which check for plagiarism. Dawson adds: “I’m not convinced that cheating is more or less prevalent than in years past. It’s just different.”

Dawson believes that time pressure and a higher cost of living have made many people rely on extra sources of income other than their basic salary to live, which can make more people consider unethical or illegal ways to make money. As well, pressures on students to pass exams can make cheating an attractive option for those starved for time.

How to improve

There is good news for those of us who feel guilty and may want to improve our behavior to be more honest in the workplace.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA good sense of perspective can diminish any temptation to cheat, according to research from Harvard Business School that examined whether exposure to other people’s behaviour can increase your own dishonesty. It found that when a member of a group behaves dishonestly, it made the group as a whole more likely to behave the same way.

In the study, a group of friends observed a member of their own group cheating at a test, which in turn made them more likely to cheat. But when a group observed a stranger cheating, the group’s ethics and behaviour changed in a different way – that is, seeing a stranger cheat actually made the group of friends more likely to honestly complete the test.

“The threshold of unacceptable behaviour is not fixed. Rather, it depends on the perspective through which people view their actions,” concludes Schurr.

So, perhaps if we want to become more honest, it may be a good idea to keep our dishonest rivals close, to maintain perspective on our own behaviour.

To comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Capital, head over to ourFacebook page or message us on Twitter.