Why the Canadian town of Asbestos wants a new name

Many towns have unfortunate names. Some make money off them, others change them. What’s the best option?

Finding ways to attract new business opportunities and investors is never an easy task for any town, especially in today’s hypercompetitive, global market. But that mission gets even tougher when you happen to be named after a carcinogenic mineral banned in nearly 60 countries.

Such is the plight of Asbestos, a small French-Canadian community in south-eastern Québec, Canada.

“One of our economic development employees was in the US last year for a congress, looking for international opportunities,” recalls Caroline Payer, a town councillor for Asbestos. “People were even refusing his business card because Asbestos was written on it, and they thought that maybe even the card was dangerous. When you start off like that, it’s not great.”

Such snubs have now driven Asbestos to drastic measures. Between 14-18 October, its 6,800 residents will vote to rename it either L'Azur-des-Cantons, Jeffrey-sur-le-Lac, Larochelle, Phénix, Trois-Lacs and Val-des-Sources, a shortlist that was extended from four to six names earlier this month after residents complained they did not have enough choice. It is an expensive process that will cost in the region of USD$100,000 (£78,000, CAD$133,000) to complete, but the town’s leaders are convinced it will yield benefits down the line. “We are losing great business opportunities just because of our name,” says Payer. “It’s very sad.”

It was not always so. A once-coveted mineral, asbestos was mined in the town for more than a century, for use in construction and manufacturing industries. The gigantic 2km-wide Jeffrey Mine created thousands of well-paid jobs in the community, shaping its development and identity.

Alamy

AlamyBut from the 1920s onward, evidence has increasingly emerged linking asbestos to diseases such as mesothelioma – a type of cancer that develops in the lining that covers the outer surface of some of the body's organs – and lung cancer. The World Health Organization has estimated in the past that annually, more than 100,000 people worldwide die from illnesses related to asbestos exposure. In 2011, the Jeffrey Mine was closed for good.

Since then the town has tried repeatedly to revamp its image, and generate new means of supporting the local economy. There was an attempt to turn the Jeffrey Mine into an adventure-tourism hub, complete with rock climbing and mountain-biking trails, although this did not get off the ground due to public health concerns. According to Payer, they employed branding and public relations consultants to redesign the town’s logo and website, and sent representatives on numerous business prospecting trips to persuade companies to invest in the town.

It has all been to no avail. “Last year there was a company who was thinking of our town to implement its business, which would have created 30 new jobs,” says Payer. “But one of their main criteria was to choose a place with a name that would not cause trouble at shipping or exporting, and so we lost that opportunity. It’s one of many similar examples in the last few years.”

In a broader sense, Asbestos’ struggles highlight the economic implications of a place name, especially if it develops negative connotations over the course of time, or happens to be perceived as unusual. How towns adapt to this varies, depending on the community, and the name itself. Some have gone to great lengths to change, while others have embraced the attention and found ways to exploit their name as a lucrative source of revenue.

The value of a name

For the French town of Vandals, the unwanted tourism associated with its name proved too much to bear. In 2008, the community – which lies just south of the city of Metz – voted to be renamed Vantousiens in a bid to disappear from the public consciousness. As town mayor Claude Vellei commented at the time, “Too many visitors come here expecting to meet the wrong kind of people. We're not vandals, and there is no reason why people should refer to us in this way."

But such a name can hold enormous commercial value. Perhaps the most long-standing example of this is the Norwegian village of Hell – its name stems from the Old Norse word ‘hellir’, meaning cliff cave – which has been a popular tourist destination for almost a century. In the 1930s, the New York Times reported Americans visiting the village to pose for photographs next to the railway station sign, and purchase ‘Hell is frozen over’ postcards. The publicity has enabled Hell to stage numerous events including the annual Hell Blues Festival, and even the RallyCross World Championships.

Alamy

Alamy“The name has made Hell into a travel brand,” says Kjersti Greger, Trøndelag’s marketing and communications manager. “The people who live there have even put up a Hollywood-style Hell sign on the hillside to make it more visible.”

In recent years, others have sought innovative ways to capitalise on their names, through the power of social media. The towns of Boring, US; Dull, Scotland; and Bland, Australia – all named after the surnames of original settlers – have united to form the League of Extraordinary Communities on Facebook, a partnership that has been featured in advertising campaigns for Coca-Cola, Unilever and Jaguar.

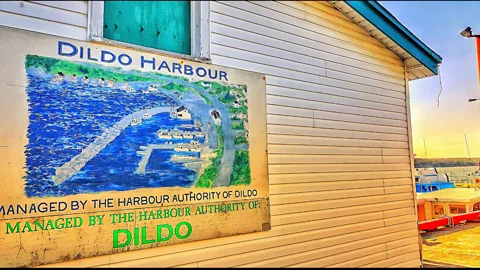

Some towns have overcome embarrassment over their names to cash in. The Newfoundland fishing community of Dildo is thought to have been originally named after the oar pivots in rowing boats, but by the mid-1980s, some residents had grown tired of the mockery. They campaigned to change the name either to Seaview or Pretty Cove, but the majority of Dildo’s citizens voted to keep it the same.

Thirty years later, that decision has paid off. Nearly 40% of the town’s 1,200 inhabitants make their livelihoods out of American and Canadian tourists who have read about the name, according to Dildo local service district committee member Andrew Pretty. “We don’t have to market ourselves, it just happens for us,” he says. “Some tourism destinations spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on marketing. We don’t have to spend a cent.”

Alamy

AlamyIn 2019, US talk show host Jimmy Kimmel even announced a spoof campaign to become the mayor of Dildo, which subsequently boosted the town’s tourism influx to such an extent that the local cell phone towers became overloaded. “The interest has increased tenfold since Jimmy Kimmel,” says Pretty. “We’ve had new businesses setting up in Dildo, with no connection to the community whatsoever, just because they think it’s a hotspot right now.”

Having witnessed first hand the income that can be generated through an odd name, Pretty expressed a degree of surprise at Asbestos’s decision to change. “If they change their name to something generic, they’re no longer going to stand out,” he says.

Misaligning interests

Asbestos may not wish to stand out but in the eyes of branding experts, shedding the legacy of its tarnished history will not be easy, even with a name like Phénix or Trois-Lacs.

“It would be relatively straightforward for a prospective investor looking to move there to discover that this was the town formerly known as Asbestos,” says Andrea Insch, a researcher at New Zealand’s Otago University, who specialises in place marketing. “You can’t bury that history that easily, then next day wake up, and it’s a new town.”

Some communities have fared better than others when it comes to changing their name for financial gain. Having been lampooned in the hit 2002 film Ali G Indahouse, the UK town of Staines announced in 2012 that it was changing its name to Staines-upon-Thames. Led by a local business forum, the idea was to discourage associations with the film and rebrand Staines as a hub for start-ups by emphasising its close proximity to London.

It proved successful. A 2015 survey by chartered accountants UHY Hacker Young found that between 2013 and 2014, Staines-upon-Thames had seen the largest increase in new businesses per 10,000 population in the UK. The analysts noted that although the town had previously struggled to attract companies, the name change, in combination with a promotional campaign from the local council to raise awareness of its advantages, had transformed its reputation.

Alamy

AlamyOther initiatives have struggled to get off the ground, typically because economic interests and those of the residents do not always align. Four years ago, a group of workers in Blenheim, one of the centres of New Zealand’s wine and hospitality industry, launched a campaign to rename the town Marlborough City to capitalise on wine tourism and the global recognition of the Marlborough wine region. But while the campaign garnered the support of local tourism bodies and corporate wineries, it was ultimately scrapped after attracting the ire of Blenheim’s citizens.

“I thought we would have seen at least a 10 to 15% growth in tourism income on the back of where we were already going,” says Mitchell Gardiner, who initiated the campaign. “But things escalated dramatically and the public backlash was too great. I was getting abused in the supermarket. I still think that there’s the potential to do it in the future, but it might have to wait a generation or two.”

In the upcoming vote, Asbestos residents are not being given the option of sticking with the existing name, even though some still object to the name change. But Insch says that managing such emotions sensitively will be important if the town is to successfully reinvent itself. “You have to consider the perspective of the locals to the place, why they are defensive of that name and want to keep it,” she says.

Asbestos’ councillors say that the main vision behind the name change is to improve the prospects for the future generation, and they expect the benefits to emerge over the course of a decade or more – which is why they have set the voting age at 14.

“We’re very realistic about it,” says Payer. “We don’t expect that there will be a big miracle and suddenly everyone’s going to come here. We feel the positive impact will be seen in five, maybe 10 years, which is why we’re involving the next generation. Those young people are going to live in this town for much longer than we are. For their sakes, when you lose one job because of your town’s name, it’s one too many. We believe that by changing the name, we are turning toward the future, and creating the toolbox to go forward and have a good economic development.”