Chile’s wild pirate island

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonThis small and remote isle has played host to buccaneers, explorers, shipwrecks and one very famous whale.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonAccording to folklore, Chile’s indigenous Mapuche people believed the spirits of the deceased were taken to Mocha Island. The tiny teardrop-shaped isle lies about 35km off central Chile’s Pacific coast and its dark-green slopes are easily visible from the mainland. But Mocha is far from easy to reach.

There are no passenger ferries or public boat services. The only way to get to the mountainous 48-sq-km island is via a six-seat, single-propeller plane from the mainland fishing village of Tirua. Stepping out onto the windswept airstrip, Mocha could hardly feel more remote.

But Mocha’s relative isolation and tranquillity belies centuries of commerce, conflict and upheaval. Pirates have come and gone, boats have run aground, and the island has been shaped by the sea and its many shipwrecks.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonIsla Mocha was not the most isolated place in the world. No, the conditions of world politics during the 17th Century placed it in the eye of the hurricane,” wrote social anthropologists Daniel Quiroz and Juan C Olivares.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonA single earthen track winds its way around the coast of Mocha Island, and it’s not uncommon to see locals (called Mochanos) getting around by horse and cart. The road connects Mocha’s roughly 800 residents, most of whom live in small bungalows dotted across the island.

Apart from a couple of shops selling basic groceries, there’s little in the way of amenities; the nearest hospital, high school and supermarket are all a plane-ride away. Aside from television and electricity, life hasn’t changed much here in the last four centuries, and today, most Mochanos continue to live off the land, just as the Mapuche did before them.

The Mapuche who inhabited the island until the 17th Century were masters of both land and sea. Archaeological evidence suggests they were skilled sailors and fishermen as well as adept farmers. They brewed chicha, an alcoholic drink made from fermented corn, and raised llama-like guanacos, whose wool they used to make clothing.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonMuch of what is known about Mocha’s indigenous inhabitants comes from the testimonies of early sailors and explorers. The Spanish came here first, briefly dropping anchor in 1544 and reportedly leaving several dead Mapuche in their wake. But perhaps the most dramatic encounter was in 1578, when notorious English privateer Francis Drake stopped off during his famous circumnavigation of the globe.

Drake’s chaplain, Francis Fletcher, wrote of the island: “We found it to be a fruitful place, and well stored with sundry sorts of good things.” The locals seemed friendly at first, offering the landing party “two very fat sheep”, wrote Fletcher. Things soon turned sour, however, and “by shooting their arrows, [the islanders] hurt and wounded every one of our men”. Drake managed to sail on and eventually completed his voyage, but according to legend, the Englishman’s face was scarred during the skirmish – a lasting memento of his run-in with the Mapuche.

Dea Picture Library/Getty

Dea Picture Library/GettyAccounts suggest that by the 17th Century, relations between navigators and the Mapuche had improved. Dutch explorers Olivier van Noort and Joris van Spilbergen visited the island separately in the early 1600s, and their testimonies suggest they were largely welcomed.

Over the years, the islanders began to see visits by outsiders as beneficial, and Mocha soon became a haven for foreign ships navigating the Pacific. The islanders were more than willing to part with their livestock, corn and potatoes in exchange for the sailors’ steel, which they would sometimes sell on to their compatriots on the mainland.

Meanwhile, the English and Dutch privateers, who left the island rested, fed and loaded with supplies, would sail on up the Pacific coast, sometimes sacking Spanish ships and ports along the way.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonDrake, van Noort and van Spilbergen may have been lauded in their homelands for their daring adventures, but in the eyes of the Spanish, who occupied Chile from 1540 to 1818, they were no more than pirates. The islanders, seen as enabling their exploits, were proving too troublesome. In 1685, a Spanish fleet led by Jeronimo de Quiroga arrived to clear the island, torching the islanders’ crops and straw huts.

Those who survived were rounded up and packed onto ships destined for the mainland, where they were resettled on the banks of the Biobío River. The Mapuche would never return to Mocha, and over the next century, the island gradually became wild again, as plants swallowed up what little remained of the islanders’ settlements.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonHad it not been for the whim of American author Herman Melville, Mocha Island could have become a household name. Even those who haven’t read Melville’s 1851 classic, Moby Dick, are familiar with the eponymous whale, but few are aware of the novel’s inspiration. In 1839, Knickerbocker magazine published the purportedly true account of a white sperm whale that frequented the seas off Mocha Island. Its name? Mocha Dick.

The article, written by American explorer Jeremiah N Reynolds, described how the mighty Mocha Dick survived dozens of encounters with whaling ships. “From the period of Dick's first appearance, his celebrity continued to increase, until his name seemed naturally to mingle with the salutations which whalemen were in the habit of exchanging,” Reynolds wrote. “Any news from Mocha Dick?” they’d say to each other at port.

Dea/Biblioteca Ambrosiana/Getty

Dea/Biblioteca Ambrosiana/GettyFollowing an epic standoff in the 1830s in which the fierce whale was finally killed, the first mate on the embattled ship was quoted as saying that in Dick’s back were found “not less than 20 harpoons … the rusted mementos of many a desperate encounter,” adding, “Mocha Dick was the longest whale I ever set eyes on.”

Today, Mochanos maintain a strong connection to the tale. The waters between Mocha and the Chilean mainland were a prime hunting spot for whales in the early 19th Century, and whalers would sometimes seek refuge on Mocha’s shores. In fact, bones from beached sperm whales continue to wash up onshore and islanders proudly display them in or outside their houses today.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonAside from the occasional visit by whalers, Mocha was left largely abandoned from when the Spanish burned it in 1685 until the mid-19th Century. In 1857, the island was leased to Chilean businessman Juan Alemparte, who took the first steps to reintroduce farmers from the Chilean mainland, and the arable lowlands were later divided into 32 private lots that remain today. Many of the islanders work the land, tending to the sheep and cows that roam between the beach and forest.

The last few decades have seen a small but thriving tourist industry emerge on Mocha, with fishing, birdwatching and hiking drawing intrepid travellers from Chile and beyond.

The lack of development on Mocha has allowed an almost-impenetrable virgin forest to thrive on its central highlands, and 45% of the island is now a protected nature reserve. Hiking up from the beach, the howling wind is suddenly muffled, replaced by a chorus of birdsong echoing through the olivillo and arrayan trees. The island is home to at least 70 different species of birds, including the vulnerable pink-footed shearwater, which nests in the small hollows and caves formed by the forest’s thick roots.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonWe don’t use clocks much here. The urgency of the city doesn’t exist,” said Hernan Neira, owner of one of the island’s two hotels.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonNeira’s tourist lodge is nestled against a curved swathe of forested hillside near the island’s northern tip. He wanted it to serve as an homage to Mocha’s nautical history, and spent more than a decade filling it with artefacts and oddities. In the middle of the lobby lies a rusty boiler, several metres tall, which was stripped from a beached steamboat and today serves as Neira’s fireplace.

In his younger days, Neira would scuba dive among the wrecks searching for nautical relics. The largest items came from the shoreline and required a digger to extract them from the sand. “Some things were very difficult. It took months of work to retrieve them,” he said.

Neira says there may be plenty more treasures hidden beneath the surf. “Many people have come searching for a galleon called the Rosetta, which was carrying a shipment of gold to Europe,” he said. “Legend has it that it sunk between the coasts of the island and Tirua.” But weather conditions mean divers and scavengers must choose their moment carefully. “It’s when the island feels like it, not when you feel like it,” Neira said. “The island is fickle like that.”

Tom Garmeson

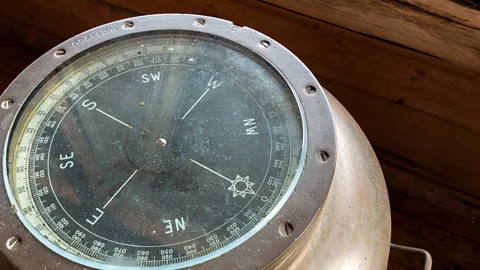

Tom GarmesonIt’s no coincidence that this little island is home to so many shipwrecks. “Mocha Island has a magnetic deviation which tricked ships’ compasses, leading them off course towards the island,” Neira said. “The coasts are very shallow, no more than 1 or 1.5m all the way around.” By the early 1900s, the Chilean navy had installed lighthouses on Mocha in a bid to solve the problem, but nature still intervened.

In 1960, the largest earthquake in recorded history struck Chile. Registering 9.5 on the Richter scale, the quake unleashed a tsunami of such force that by the time it reached Japan’s coast, more than 17,000km away, the waves were still 5.5m tall. Amid the chaos, a steamboat named Santiago was torn from its moorings in the Chilean port town of Corral, and somehow ended up more than 160km to the north, trapped off the coast of Mocha Island.

The islanders went to help the captain salvage what they could, and parts of the ship still adorn the walls of some local homes. Its anchor remains in the water; Neira hopes to reclaim it when the tides, wind and waves permit.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonWhile locals ponder the potential riches hidden beneath the waves, some archaeologists argue the island has already revealed a more fascinating secret.

In 2007, researchers re-examined a set of human skulls found on Mocha that had lain forgotten for decades in a museum archive in the Chilean city of Concepción – and made some surprising finds. Some of the bones appear to belong to Polynesians dating from between 350 to 1290, backing the theory that ancient Polynesians managed to sail some 7,500km across the Pacific and reach South America well before Europeans.

In addition to the skulls, other clues suggests a cultural connection between the two distant groups. Similarities between tools, words and customs in Pacific and native South American communities have been observed by many anthropologists over the years, and a major breakthrough came in 2007 when chicken bones found further up the Chilean coast were carbon dated to the pre-Columbian period, with DNA tests suggesting that the animals came from Polynesia.

Tom Garmeson

Tom GarmesonUnlike the Dutch sailors of the 17th Century, the Polynesian explorers left no journals behind, and more evidence is likely needed to convince the sceptics that transpacific contact did indeed occur. But the fragments of information that archaeologists, anthropologists and linguists have spent years piecing together point towards one of the most spectacular journeys in human history. And yet again, it would seem that little Mocha Island played a part in the odyssey.

To the Ends of the Earthis a multimedia series from BBC Travel venturing to some of the most remote corners of the planet and unveiling what it’s like to live there.