The superbugs lurking in seas and rivers

Chris Turns

Chris TurnsDrug-resistant superbugs are on the rise, prompting researchers and campaigners in the UK to call for a water system clean-up.

I'm a goggles-on, face-underwater kind of swimmer, yet these days I hesitate before I dip my head beneath the surface of the sea. In recent years, increasingly frequent spills have released millions of hours-worth of untreated sewage into UK rivers and coastal water. The immediate health risks are numerous: exposure can lead to acute sickness, ear infections or a tummy upset. But that's not all – there's another potential health hazard lurking in those polluted waters.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) develops when the genetic codes of pathogens, including bacteria present in sewage, mutate to resist medicines designed to control infections. Infections caused by the resulting drug-resistant pathogens, sometimes referred to as "superbugs", are estimated to be directly linked to 1.27 million deaths each year and the UK's special envoy on antimicrobial resistance, Dame Sally Davies, has called this threat "a global antibiotic emergency". By 2050, AMR could cause 10 million deaths annually, according to the UN Environment Programme.

The World Health Organization (WHO) labels AMR a "silent pandemic" because it's a serious threat to public health globally – yet it's not often talked about by the media or policymakers.

Untreated sewage is one possible avenue for AMR's spread. And once untreated sewage pollution containing AMR reaches the environment, people – including swimmers like me – can be exposed. But while sewage spills regularly make headlines, AMR often gets overlooked.

So behind the scenes, scientists are working hard to quantify which sources of AMR are the most dangerous and which solutions could be the most effective to reduce the spread of AMR. Not only in the UK, but globally too.

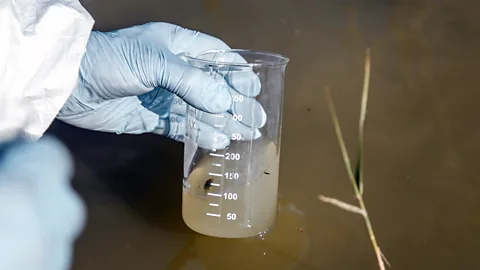

Dirty waters run deep

Curious about whether I have ingested any AMR, I'm getting tested to check whether my guts have been colonised by a particular type of antibiotic resistant E. coli. A quick, simple and not-so-glamorous screening test involves sending a faeces sample off in the post to Elitsa Penkova, an evolutionary microbiologist at the University of Exeter in the UK. As part of her PhD, she's coordinating the Poo-Sticks project to assess the link between sewage pollution in UK rivers and antimicrobial resistance in swimmers and non-swimmers – by analysing poo samples from 300 people.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile I wait for my results, Penkova explains that humans don't metabolise antibiotic medicines well: "Up to 70% of these antibiotics can be excreted via urine and faeces", so some get unknowingly flushed away down the toilet.

Sewage pollution includes effluent from waste water treatment plants, combined sewer overflows that discharge raw sewage into waterways when the system becomes overloaded, such as during heavy rainfall, and septic tanks. Hospital wastewater is another source of antibiotics. And around half of all the world's antibiotics are used on farms, so agricultural run-off is a major concern.

Antimicrobial residues end up in soil, river sediment, waterways and oceans. A new water quality report from environmental charity Earthwatch Europe concludes that 75% of the UK's rivers are in poor ecological health. (Read more about the efforts to clean up the UK's sewage-infested hotspots.)

Sign up to Future Earth

Sign up to the Future Earth newsletter to get essential climate news and hopeful developments in your inbox every Tuesday from Carl Nasman. This email is currently available to non-UK readers.

In the UK? Sign up for newsletters here.

"Polluted rivers offer favourable conditions for the emergence, spread and maintenance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria," says Penkova, whose research follows the University of Exeter's 2018 Beach Bums study, conducted in collaboration with Surfers Against Sewage, an environmental non-profit campaigning for cleaner, safer waters.

During this research, comparisons of faecal samples from UK surfers with people who don't go in the sea showed a strong association between water users and AMR. Guts of surfers were about three times more likely to harbour antibiotic-resistant E. coli – a bacteria listed as a priority pathogen by WHO that grows in the presence of cefotaxime, a common antibiotic – than non-surfers' guts. Researchers also found that surfers swallow up to 10 times more water than sea swimmers so could potentially be more vulnerable to ingesting antibiotic resistant bacteria.

However, a 2023 Irish study found that coastal swimmers were less likely than non-swimmers to carry antibiotic resistant bacteria in their guts. Those results contradicted the Beach Bums results, possibly because swimmers swallow smaller volumes of water than surfers, suggests Penkova.

Polluted rivers aren't a threat solely to swimmers and surfers. "There are many ways you might ingest AMR," says Giles Bristow, chief executive of environmental non-profit Surfers Against Sewage (SAS). "Some people might paddle or walk into the water after their dog – if they have a cut on their foot, for example, AMR might get into the bloodstream. Polluted water can also get into your ears, eyes or mouth."

Sasha Woods

Sasha WoodsWhile carrying AMR doesn't necessarily make someone poorly, and that bacteria can be excreted without causing problems for healthy people, continuous exposure does increase the risk that AMR gets passed on to someone more vulnerable to infection. "It's a nasty bug," says Penkova. "It's hard to prevent [serious illness] because these superbugs are easily transmissible and there are limited treatment options for AMR infections – antibiotics simply won't work. That's the biggest concern."

Currently, when rivers and coasts are monitored by government authorities (the Environment Agency in England, Natural Resources in Wales, and Scotland's Environment Protection Agency) for sewage, levels of just two prevalent bacteria – E. coli and intestinal enterococci – are measured because they are well-studied and predictable. Yet these indicators only give a snapshot view of river health status and subsequent risk of AMR spread, as Bristow explains: "There are thousands of different species of increasingly antimicrobial resistant bacteria that are pathogenic. Our sewage system is a breeding ground for AMR," he says.

How to hold back the bacterial tide

Wastewater is a major contributor to AMR. Treatment plants act as both a sink and a hotspot because it's where bacteria from faecal material are removed, whether they carry resistance genes or not. It's also where those bacteria mix with other bacteria naturally present in the activated sludge flocs (a gel-like material covered with masses of microbes that biodegrade organic material and filter out most pathogens). The high nutrient concentrations on these flocs mean that bacteria reproduce quickly and genes, including those for antibiotic resistance, can transfer faster.

Jan-Ulrich Kreft, associate professor in computational biology at the University of Birmingham in the UK, studies the complexities of wastewater treatment plants and aims to quantify the pathways of transmission of AMR through the environment. "We don't yet know whether the run-off from cows or manure spread on fields is as significant as the human sewage pathway. Once we know that, we can prioritise interventions and gauge progress from that baseline."

"Wastewater treatment plants remove all bacteria – and their resistance genes – by about 100-fold as a rough rule of thumb," says Kreft who explains that untreated sewage is always significantly worse that treated sewage.

In the UK, all human sewage gets treated except effluent released via combined sewer overflows (often but not always during rainy weather), or sewage that leaks out of holes or cracks in the old, often Victorian, pipes. Nobody knows exactly how much untreated sewage gets spilled but one study calculated that 11 billion litres (2.4 billion gallons) of untreated sewage was discharged from just 30 UK wastewater treatment plants in 2020 – equivalent to the volume of 4,352 Olympic-sized swimming pools. For that reason, Kreft argues that the installation of volume metres at storm overflows should be a legal requirement: something recommended by the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, but left out of the 2021 Environment Act.

A little AMR can also remain in treated effluent and E. coli is one of the bacteria that doesn't bind to the sludge flocs – instead it flows through the system and out into the waterways.

Getty Images

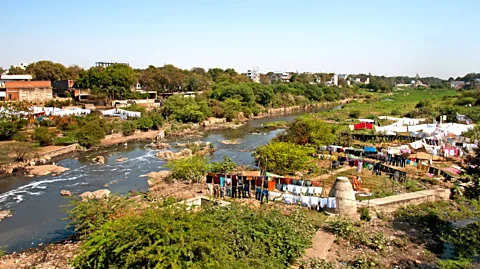

Getty ImagesIn developing countries the situation can be much worse, Kreft says. In India's Musi River, where only about 20% of sewage gets treated because the population is growing faster than treatment plants can be built, urban rivers are full of raw sewage. "Treatment plant effluent is actually cleaner than the polluted river water," says Kreft.

AMR is a mobile entity, moving around the globe via shipping and tourism – so improving wastewater treatment in developing countries would help tackle the AMR issue in the UK, says Kreft. In fact, the UK government recently pledged £85m ($108m) to support international efforts to improve access to antimicrobial drugs in Africa and monitoring of AMR globally.

"It's a global problem – people travelling from countries in Southeast Asia are likely to return with resistant bacteria in their gut," says Kreft. "Airplane toilets are full of AMR and these resistant bacteria can stay in the gut for a few months. It might not be a problem, but if you get ill and take a course of antibiotics, then you're selecting for resistant bacteria. If resistant genes transfer to the pathogen causing your infection, the medicine won't work."

In 2022, scientists at the University of York in the UK led a global project monitoring pharmaceuticals that carried out the first worldwide investigation of medicinal contamination in the environment. Of 258 rivers across the globe tested for 61 pharmaceuticals, a quarter tested positive for some, including commonly used antibiotics, at high enough concentrations to drive the evolution of AMR.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe AMR problem is also forecast to worsen as the growing world population puts greater demand on existing sewerage infrastructure and increases the need for more wastewater treatment plants. Climate change-induced extreme weather is a threat multiplier too. During droughts, sewage in waterways becomes more concentrated, while floods increase the run-off from agricultural land and overwhelm sewers, causing raw effluent to divert into rivers.

Carbon Count

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

"When rivers flow fast, some bacteria in the river sediment become resuspended and released back into the water column, so it's a good idea not to swim in rivers after heavy rainfall," warns Kleft. Rising temperatures have an effect too. Bacteria grow more quickly in warmer sediment or water and a 2018 US study found that an increase of 10C (18F) is consistently associated with increased levels of AMR in common pathogenic bacteria.

In the UK, however, there are growing calls for a sewage-system clean up. In 2023, 1,924 people reported getting ill after entering UK waters, as outlined in SAS' latest water quality report. According to Bristow, "about 60% of those cases were in bathing waters classified as 'excellent'; the places that we encourage people to go in and swim".

Bristow says his non-profit is pushing for an independent inquiry into the issue of sewage pollution and widespread lack of water quality monitoring. "[AMR] is not a future threat – it's a now threat and our waste treatment systems are absolutely central to building resilience,” he says.

According to a spokesperson for Water UK, the trade association for water and wastewater companies, research shows that wastewater treatment works "are effective" at removing AMR genes and organisms from effluent. Water companies have also proposed prices hikes to fund further investment in infrastructure, including treatment works, some of which the industry's economic regulator Ofwat has approved.

Countries with advanced AMR monitoring strategies, such as Iceland, Finland and Slovenia, also have some of the cleanest waterways in Europe. So one solution, Bristow suggests is to better resource the UK Environment Agency – the government department monitoring water quality. "There's a huge lack of monitoring so we don't really understand what's in our rivers and coastal waters," he warns.

According to the UK Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra), both its department and the Environment Agency are also part of a £24m ($31m) Treasury-funded pathogen surveillance in agriculture, food and environment (Path-Safe) programme. This aims to detect and track pathogens and associated AMR through the food and water system, and has been trialling new approaches for environmental surveillance.

More like this:

• The unnatural impacts of natural gas

• How unhealthy air changes body and mind

• Parisians save 'le pipi' to help the Seine

"I don't think people realise how urgent this is….it's not something we often talk about because it's unpleasant and scary," says Penkova, who wants policymakers to urgently prioritise this issue and tackle systemic antibiotic overuse in both the medical sector and industrial agriculture.

But there are also steps individuals can take too, she adds: "The first step is to avoid overusing antibiotics, always finish a course of medicine and stop wasting antibiotics".

Furthermore, the development of new, targeted antibiotics is another frontier in AMR prevention, with some signs of promise. Microbiologists at Queen's University Belfast recently identified how a bacteria protects itself from the effects of antibiotics and this could lead to novel drug development in the future. Meanwhile, chemists at King's College London have discovered a way to speed up the production of new antibiotics. Researchers at the University of Stirling in Scotland are also developing a new, low-cost system for monitoring freshwater quality that uses innovative sensor technology and artificial intelligence to flag polluted waters.

Josh Kubale

Josh KubaleAfter a few days, Penkova gets in touch with the results of my E. coli test. My sample doesn't show any evidence of AMR which is good news…for now. A person's gut microbiome is dynamic – it fluctuates depending on the food and drink they consume, the people they interact with and the places they visit. But Penkova doesn't want to put people off swimming: "I want to empower people to become more informed and call for change to clean up our waterways," she says.

While confirmed presence of E. coli cannot be definitively linked to the waters someone swims in, scientists like Penkova are working hard to quantify those links and encourage greater antimicrobial stewardship within healthcare and farming – that begins with doctors and vets only prescribing antibiotics when essential and appropriate, so not as a preventative measure or to treat viral infections that won't respond to antibacterial drugs.

On a personal level, I'll definitely be avoiding any default use of antibiotics unless absolutely necessary and I'm going to do my best to avoid exposure to AMR in the environment too. I will be checking for pollution forecasts more carefully via the SAS safer seas and rivers service app, I definitely won't be swimming in rivers or coastal waters after heavy rainfall, and I'm taking the unused antibiotics in my bathroom cabinet back to my local pharmacy to be disposed of safely.

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and X.