The factory making spacecraft for new Moon missions

Airbus

AirbusThe Artemis missions will take humanity further into space than ever before. One crucial part is being built in a hangar in Germany.

Two hundred years ago the Brothers Grimm shared a story about four animals who decided to leave their exhausted lives behind, become musicians and head to the German city of Bremen.

As with all fairytales, there's a twist. They never reached the city. But today a bronze statue - a rooster standing on a cat, on a dog, on a donkey – is a reminder of both the country's famous storytellers and that Bremen was an aspirational destination. Today is no different because the "aerospace city" has Europe's Moon mission factory.

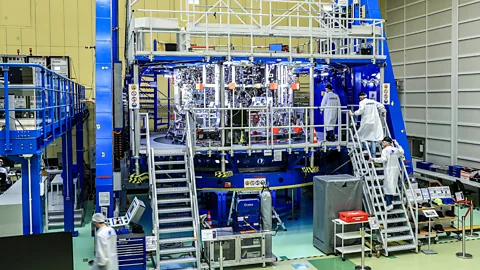

Inside the high-ceilinged cleanrooms at Airbus Bremen, three European Service Modules (ESMs) are currently being built. "Here is the freshest model, ESM-5," says Hagen Witte, head of the ESM assembly line.

The ESMs are essential powerhouses for Nasa's Artemis missions to the Moon. Designed to provide propulsion, electrical power and life support for astronauts, ESM-5 is joined by ESM-4 and – the celebrity of the bunch – ESM-3. "This is the module," says Witte, "that will bring the next humans to the surface of the Moon."

There's an understandable pride in Witte's voice and not just for the engineering. It's been over 50 years since a human footprint graced the lunar surface and ESM-3 will enable the first woman and person of colour to land on the Moon.

Yet when I first set eyes on ESM-3, I laugh unexpectedly. Because while ESM-5's partial completion is a silver futuristic mass of mechanisms, at this earlier stage ESM-3 reminds me of the insides of a 1970s stereo.

Airbus

Airbus"Yes, you see a lot of wires and tubes already integrated," says Witte. "At the moment I'd say it's about 70% complete. You're missing the big parts – like the advanced electronic equipment and the tanks. That's why it doesn't look as much if you compare it to the other structures."

This is hardly surprising. "There are 22,000 parts per module. It appears already full but the amount of parts still to come is incredible."

Each ESM is 4m (13.2ft) wide, 4m high, will take 16 months to complete and, on launch, weigh around 13 tonnes. ESM-1 has already flown successfully. It launched on 16 November 2022 as part of the Artemis I mission and propelled an uncrewed Orion capsule into lunar orbit on a 25-day return mission.

You might also like:

- Artemis I: A giant rocket to set new records

- Just how loud is a rocket launch?

- What it's like to live in Nasa's new spacecraft

The inaugural ESM used four 7m-long (24ft) wings, each consisting of three solar panels, to help propel an uncrewed Orion capsule on a 25-day return mission into lunar orbit. The rest of the ESMs are on the production line, in various stages of completion, designed to provide propulsion, electrical power and life support for astronauts.

"It's like a factory and this is what we are proud of," says Ralph Zimmermann, Orion ESM project manager at Airbus. "We are contracted for six ESMs right now. The first one has flown. The second one has been delivered to Kennedy Space Center (KSC) and is in a testing phase and will undergo further integration with the crew module. And then there's numbers three, four and five that you can see here in the clean room in different states of integration."

ESM-4 is at a more advanced stage than ESM-5, which is currently being integrated with internal components, such as mechanical and electric subsystems. ESM-3 will be delivered to Nasa, from the airport on the site's doorstep, in October, where it will be integrated with solar arrays, mated with the Orion crew module and prepared for launch in 2025.

"It's a really exciting time in this programme," says Sian Cleaver, Airbus' Orion European Service Module industrial manager. "Up until now, it's been a dream that we would fly this one day. Some of our engineers have been working five, 10 years on the programme and it's exhausting at times. It's hard work to build something like this. So now that we've had the first launch and that mission went phenomenally well, better than we even expected, there's a new sense of energy."

The site has a good track record. Between 2008-15, its five Automated Transfer Vehicles (ATVs) delivered supplies to the International Space Station (ISS). A model of an ATV with solar panels is on the grass outside the building and its resemblance to an ESM is striking.

Philippe Deloo, ESM programme manager for the European Space Agency (Esa), which has the contract with Nasa to produce the spacecraft, immediately puts me right. "No, no, no. It's a completely new design because it's a completely different spacecraft and a completely different mission."

Nasa

NasaDeloo concedes that "they look very similar but it's a completely different technology. If you look deep inside, the ATV didn't have a main engine of 26 kilo Newtons, which is the engine from the Shuttle. The solar arrays look the same but are much more efficient than the ones on the ATV. Plus, the ESM is a human-rated design."

The ESMs will also evolve if anything doesn't perform as well as expected when they are tested. "If there needs to be a correction, there will be correction," says Deloo.

"This is the first time that Nasa has ever entrusted a core element of our flagship human-rated spacecraft, to an international partner," says William Hartwell, Nasa's Orion programme liaison to Esa. "You don't make a commitment to a partnership like that lightly."

"The decades of cooperation between Nasa and Esa are at the foundation of the expertise," Hartwell adds. "The technologies that Esa developed and implemented on the ATV were spot on and very high calibre. So we built trust."

This trust has extended across multiple endeavours. "We have constructed and assembled the spacelab which was flown on the Shuttle," says Zimmermann. "We have constructed, built and flown five ATVs. And we have also integrated the Columbus module, which is part of the ISS. Bremen really is a centre for human spaceflight in Europe."

Bremen is not the only place in Germany connected to human spaceflight. In 2019, I visited the medieval town of Nordlingen in the centre of the 25km-wide (15.5 miles) Nordlinger Ries, the best-preserved impact crater in Europe. In the distance, you can see the crater rim topped by its own set of low-lying clouds.

Around 15 million years ago, an asteroid smashed into this region leaving behind masses of extraterrestrial rocks. Even the walls of St George's Church are made from asteroid fragments. Opposite the church stands the Hotel Kaiser Sonn, where Apollo 14 and 17 astronauts once stayed and whose photographs adorn the walls.

Airbus

AirbusSince the Moon is covered in impact craters, the Nordlinger Ries proved to be the perfect geological playground for astronauts on lunar missions. A nearby quarry enabled them to train and learn how to identify impact rocks, such as suiwite, which has also been discovered on the lunar surface. Today's Esa astronauts, based at the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne, will also use the crater as part of their training. At least one of those astronauts is expected to set foot on the Moon.

Europe's Moon factory in Bremen is also looking to the future. In January, Airbus announced that it is working with Voyager Space to design Starlab, a new space station for agencies like Nasa and Esa. But for the engineers and workers involved in the ESMs, sometimes it takes fresh eyes to make them appreciate their role in spaceflight history.

"The job requires that I see more problems than fascination," says Witte. "But it's on days like these, when people are visiting and I'm able to explain what we're doing, that I also recognise what we're doing here. It's something unique.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List" – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Traveland Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.