The well-intentioned copies that went wrong

EPA

EPAAfter a botched art restoration in Spain gave St George a cartoonish facial glow, Kelly Grovier looks at artistic likenesses that have gone wrong.

The only thing more memorable than a great work of art is a truly awful one. Every so often a painting or sculpture comes to light that is such an odd likeness, the world’s toes collectively curl. Gathered together, these misfires of imagination and skill would fill a curiously compelling museum of fumbled face and form – one capable of proving, paradoxically, the miracle of any artist ever actually seizing a sitter’s elusive essence or capturing the mysterious music of being in the world.

More like this:

- The artists who shocked Europe

Among the highlights, or lowlights, of any such collection would surely be the so-called ‘Monkey Christ’ of Mercy Church, which reared its hairy head near the town of Zaragoza, Spain in 2012. It was then that a well-intentioned parishioner tried her hand at tidying up a fading fresco of Christ by the early 20th-Century artist Elías García Martínez.

Alamy

AlamyEndeavouring to reverse decades of damage caused by damp, the elderly volunteer accidentally obliterated the subtle brushstrokes with which Martinez had captured the features of Christ’s face – burying them under layers of artlessly applied paint. The resulting portrait, which provoked gasps across the globe when photos of it went viral, appears more simian than sacred: like “a crayon sketch”, so BBC Europe correspondent Christian Fraser described it, “of a very hairy monkey in an ill-fitting tunic”.

Plaster surgery

Memories of that unfortunate restoration have been swinging their way through popular imagination recently with news of another mangled makeover, this time of a medieval statue in the Romanesque church of San Miguel de Estella in northern Spain. The defenceless victim on this occasion is a 16th-Century wood carving of the legendary warrior, St George, depicted on horseback trampling a defeated dragon under hoof. Though the priceless relic has survived relatively intact for five centuries, St George’s countenance has suddenly slipped from fierce to farce with the flick of an amateur conservator’s wrist.

EPA

EPAIn an effort to return the object to its former lustre, a local art teacher took it upon herself to freshen up the carving’s crumbling complexion with layers of modern plaster and hobby-shop paint. The perky pinkish hue with which St George’s over-polished cheeks are now permanently pinched seems more day-spa facial than dauntless old master. More Botox than Bernini. The carving’s cartoonish appearance has provoked the outrage and concern of experts who fear the defacement may be irreversible. Commenting on the bungled operation, social media users have drawn unflattering comparisons with Pee Wee Herman’s simpering pout. Others have detected a resemblance to Sheriff Woody, the lanky cowboy doll in Toy Story, as St George is left to wander clumsily into eternity and beyond.

When it comes to flubbing the human face, amateur restorers with too much time on their hands are not of course the only culprits. Artists themselves routinely miss the mark from the very start. Just ask Portuguese footballer Cristiano Ronaldo, who unveiled a bronze bust of himself by a local sculptor to a chorus of titters last year at Madeira airport.

EPA

EPAThe contorted countenance, with its weirdly warped expression and stare so wild-eyed it doesn’t so much follow you around the room as haunt your nightmares, was replaced last month by a fresh attempt by the same artist. Still awkward and unconvincing as an actual likeness of the Real Madrid forward, the do-over is less-obviously ludicrous in its fumbling of Ronaldo’s famously chiselled physiognomy. It’s bad, but in the way that many portraits are bad.

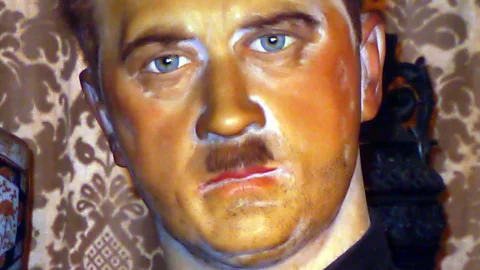

No imaginary museum of mismanaged miens would be complete without an entire wing devoted to Louis Tussaud’s notorious collection of frightfully unconvincing wax works. After half a century of inviting visitors to scratch their heads in wonder at who is being portrayed by its misshapen subjects, Tussauds House of Wax closed its doors in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, in 2014. Since then, the bungled effigies of everyone from a pudgy Sean Connery to a sun-kissed Adolf Hitler have slipped mercifully from public view as if into an artistic protection programme.

Rex Features

Rex FeaturesTussaud’s slapstick grotesqueries, which attracted a kind of cult following of fans, relied for their “success” on visitors knowing precisely how hilariously wide the gap was between flesh-and-blood subject and waxen send-up. When it comes to assessing the achievement of likenesses of bygone historical figures for whom we have no filmic or photographic record documenting their appearance, it is much more difficult to know how far any given effort has gone astray.

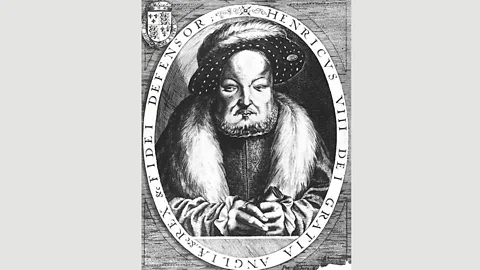

Alamy

AlamyTake, for instance, Peter Isselburg’s unflinchingly unflattering etching of King Henry VIII (after a portrait by Cornelis Metsys), whose eyes squint sinisterly above a neckless cascade of facial flab. That Henry VIII was never Tudor eye candy is clear enough from the preponderance of contemporary portraiture. But is Isselburg’s unlikeable likeness evidence of artistic malpractice or a subversive assault on the monarch, intended to suggest that it is the sitter’s abrasive spirit that defies palatable representation, not the artist’s skill?

If we really undertook to shift into an institute of ineptitude every dubious depiction from art history, what would be left? Is it possible that the rubbish portraits that occasionally stop the world in its tracks are merely exaggerated examples of the rule rather than egregious exceptions to it? Perhaps rather than being outraged by the occasional catastrophe that makes it onto the front page, we ought to awe a little louder at the masterpieces.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.