The awesome power of volcanoes

Alamy/JMW Turner

Alamy/JMW TurnerFrom Pompeii to Krakatoa, volcanoes have been the subject of art and literature for centuries. What makes them so compelling? Alastair Sooke finds out.

“There’s always something new to learn about volcanoes,” says David Pyle, professor of earth sciences at the University of Oxford. “Around 600 volcanoes have erupted within the last 200 years, and 1,500 could erupt again within the next few decades.” He smiles. “But we are never clever enough to work out what volcanoes will do next. The deadliest eruptions have always been of quiet volcanoes.”

Despite the best efforts of modern science, massive eruptions can still result in catastrophic loss of life. Since 1900, the two worst volcanic events were the eruption of Mount Pelée on the Caribbean island of Martinique, on 8 May 1902, which destroyed the city of Saint-Pierre, killing 28,000 people; and the eruption, in 1985, of Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia, which melted the mountain’s glaciers, causing mudflows to race down the volcano’s side and engulf the town of Armero, where more than 20,000 people died.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Bodleian Libraries, University of OxfordOf course, it isn’t only volcanologists who are concerned with large eruptions. Volcanoes, an ongoing exhibition organised by Pyle at Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries, reminds us that devastating eruptions – Vesuvius in AD 79, Tambora in 1815, Krakatoa in 1883 – have often fascinated humans, filling them with awe and dread. For millennia, artists and writers, as well as scientists, have felt compelled to depict and describe volcanoes.

The Bodleian’s show consists mostly of written and printed material from its collections, including letters, woodcuts, and engravings. It contains the earliest known sketch of a volcano, from the margins of an early-15th-century German manuscript of The Voyage of Saint Brendan – a Christian story about an Irish monk who sailed the Atlantic searching for paradise. Supposedly, Brendan encountered volcanic islands including one with “flames shooting up into the sky… so that the mountain seemed a burning pyre”.

There is also a beautiful map of Iceland’s volcanoes from a 1606 edition of Flemish map-maker Abraham Ortelius’s Theatre of the World, which is often described as the first modern atlas. Alongside fantastical sea monsters and delightful, tiny polar bears cavorting atop ice floes in the Arctic Ocean, the map depicts volcanoes including Hekla, once considered the gateway to chaos, and the glacier Eyjafjallajökull, which – four centuries later – erupted in April 2010, producing an enormous cloud of smoke and ash that blew across northern Europe, disrupting air travel for weeks.

Nearby, we find a fragment of an incinerated papyrus scroll from the ancient Roman town of Herculaneum, which was buried during the AD 79 eruption of Vesuvius, and a 15th-Century manuscript of the Letters of Pliny the Younger, who provided an eyewitness account of the eruption. Indeed, Pliny’s account was so accurate – recording, for instance, that the initial sign of the eruption was an unusual cloud, in the shape of a pine tree, rising from the mountain’s summit – that volcanologists still categorise this type of violently explosive eruption as 'Plinian'.

The gates of hell

According to the writer and cultural historian James Hamilton – who, in 2010, curated a brilliant exhibition of art inspired by volcanoes at Compton Verney in Warwickshire – Mount Vesuvius, on the Gulf of Naples, has had a greater impact upon Western culture than any other volcano. Principally, this was due to the discovery, during the 18th Century, of the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which were both obliterated by deadly pyroclastic surges and ash clouds during the eruption in AD 79.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

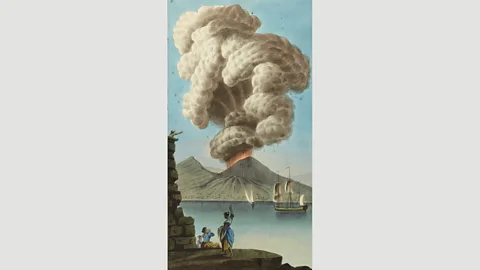

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford“The area rapidly became a magnet for tourism,” Pyle explains. “And many wealthy tourists on the Grand Tour became obsessed with Naples and Vesuvius. When they got back, they wanted to show fabulous depictions of the fabled vista of the Bay of Naples in their country houses.”

In antiquity, the region’s volcanic landscape was associated with hell: in Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid, for instance, Aeneas descends to the underworld via a cave near Lake Avernus, a volcanic crater lake not far from the volcanic Phlegraean (‘Flaming’) Fields, situated to the west of Naples. “In some Icelandic tales, Hekla is imagined in a similar way,” Pyle says.

By the 18th Century, though, people were beginning to be interested in Italy’s Campanian volcanic arc for scientific reasons. The 18th-Century diplomat William Hamilton, for instance, who was Britain’s ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples between 1764 and 1800, was obsessed with Vesuvius.

He rented a villa at the foot of the cone-shaped mountain, and monitored a cycle of significant eruptions during the 1760s and ’70s, sending informed letters detailing his observations to the Royal Society in London. Between 1776 and 1779, these were published as Campi Phlegraei (“Fields of Fire”) – described by Pyle as “one of the first descriptive monographs of an active volcano”. It remains remarkable for the vivid nature of its influential illustrations by the English-born artist Pietro Fabris.

Out of the ashes

The prospect of witnessing the spectacle of Vesuvius erupting lured many travellers, including artists such as Joseph Wright of Derby. In 1774, Wright stayed with Hamilton for a month – writing to his brother that “there was a very considerable eruption at the time – tis the most wonderful sight in nature”. During his lifetime, he painted more than 30 views of the exploding volcano. “The heyday of the visual art around volcanoes was the mid to late 1700s,” Pyle says.

The painter JMW Turner also visited Naples, in 1819, four years after he had exhibited at the Royal Academy a striking and dramatic canvas titled The Eruption of the Souffrier Mountains, in the Island of St Vincent, at Midnight, on the 30th of April, 1812, from a Sketch Taken at the Time by Hugh P Keane, Esq. “This was painted not from Turner’s own observation, but, as the title indicates, from a sketch by the barrister and sugar plantation owner Hugh Perry Keane,” explains James Hamilton, in a short book published to accompany the Compton Verney show. Sadly, for Turner in 1819, his hopes of witnessing an erupting volcano for himself came to naught. While he was in the area, Vesuvius produced nothing but a few wisps of smoke and ash.

Alamy/JMW Turner

Alamy/JMW TurnerCountless other artists have represented volcanoes. During the 19th Century, the Japanese artists Hokusai and Hiroshige both made woodblock prints featuring landscape views of the active stratovolcano Mount Fuji. In 1874, John Ruskin painted Etna from Taormina, on Sicily. Even Andy Warhol, in 1985, produced a series of large, luridly coloured canvases of Vesuvius erupting. “I painted each Vesuvius by hand,” he said, “always using different colours so that they can give the impression of having been painted just one minute after the eruption.”

Cartoonists, too, have often been drawn to volcanoes: in 1815, for instance, on the eve of the Battle of Waterloo, George Cruikshank produced a political cartoon in which Vesuvius was seen ejecting the deposed King of Naples and his wife Caroline, Napoleon’s sister. In 2010, the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull inspired a satirical cartoon by Gerald Scarfe commenting upon the campaign for a British general election.

Volcanoes have also proved attractive for writers. “The first global volcanic eruption, in terms of global news coverage, was the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883,” says Pyle. “The transatlantic telegraph network had just been completed, and so the story of that eruption was told within hours in northern Europe. Immediately, Krakatoa made it into novels. RM Ballantyne published a book called Blown to Bits, a few years later, built around the testimonies of people who had survived the eruption.”

RKO Radio Pictures

RKO Radio PicturesFilmmakers, too, have found volcanoes irresistible. The Bodleian’s exhibition contains two film posters: one for the Italian drama Volcano (1950), and another for Roberto Rossellini’s neo-realist Stromboli, from the same year, starring Ingrid Bergman. There are also lots of examples of volcano-inspired ephemera and merchandise, including ‘Vulcan’ matchboxes.

The answer may seem obvious, but why, exactly, do volcanoes exert such a hold upon our collective imagination? “There’s something visceral about peering into an abyss,” explains Pyle. “Standing on the side of a volcano, you can hear it rumble and feel it shake. People have used the same words to describe volcanoes for millennia. They offer this feeling of an awesome power that’s unlike anything you can experience elsewhere on Earth.”

Alastair Sooke is Art Critic and Columnist of the Daily Telegraph.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.