Stunning images that will change the way you see the world

Images (c

Images (cSee a tulip farm that looks like a Mondrian painting – and more striking photos of the planet’s landscapes taken via satellites in space.

“This all started as a mistake,” says Ben Grant. With fewer than 1,000 posts Grant has turned Daily Overview, a collection of satellite images of the earth that look like minimalist paintings, into an Instagram sensation with over 445,000 followers. While working at a brand consulting firm in New York City, Grant started a ‘space club’ to bring his colleagues together during their lunch hour. It simply involved using Google Earth to see how different parts of the globe appeared as two-dimensional images shot from above. The first place Grant explored was the aptly named Earth, Texas, where he was struck by how a pattern of crop circles looked like a work of modernist art – especially when given an aesthetically pleasing crop. He started posting the images captured from Google Earth on Instagram, but a concern over copyright led him to partner with DigitalGlobe, a company that runs four satellites in orbit, two of which have the high-resolution cameras Grant needs. He then scours massive photos that have 10 times the resolution of Google Earth images – each pixel, in all of the following images, represents exactly 30cm (11.8in) on the ground – and then finds framings for features that strike him as exceptionally beautiful or that demonstrate humanity’s impact on the planet. “What is different with this photography is that there is always much more information outside the frame,” says Grant. “So you’re always making a decision about what to show.” Some of his best photos are now being collected into the book Overview, published by Amphoto Books. (Credit: Reprinted with permission from Overviewby Benjamin Grant, copyright (c) 2016. Published by Amphoto Books, a division of Penguin Random House, Inc. Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

“This is an example of incredible human ingenuity,” Grant says of a massive tulip farm located in The Netherlands. “Imagine the expertise developed over centuries that results in these specific colours being produced – it’s the intersection of humanity and nature.” Grant has divided his Overview book into chapters that focus on different ways humanity has had an impact on the earth: Where we harvest, Where we extract, Where we live, Where we waste, etc. Some days when scouring the images provided by the DigitalGlobe satellites he would focus on mining, other days on energy production or agriculture. It was actually in the first four weeks of the project that Grant discovered this tulip farm, the resulting image of which reminds him of Mondrian, his favourite artist. “We were so lucky that the satellite was positioned so that it could capture this image in April when the tulips were in peak bloom,” says Grant. “For the rest of the year they don’t have that vibrant colour and there’s only a two to three week window where that’s possible.” (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

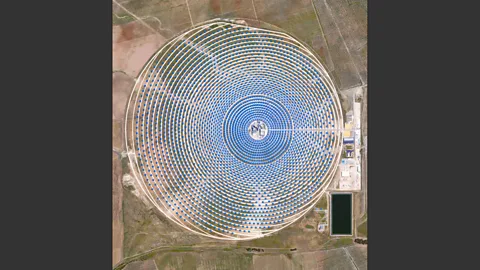

The name for Grant’s Instagram project and resulting book, Overview, comes from his interest in the ‘overview effect’. It’s a term used to describe how astronauts’ experience of seeing the earth from space leads them to perceive how small humanity’s place is in the universe. Grant’s vicarious experience of the overview effect via the satellite images has, he says “made [me] realise how little we know about our world, about what other people do for a living, and the systems we have in place to make our society work.” When searching for an image, he’ll often begin with a ‘thought experiment’ like “What are different ways that cities are powered?” That would lead to a search for elaborate solar energy collection fields, and, this one, the Gemasolar thermosolar plant in Seville, Spain, emerged as one of the most visually striking. Grant hopes that, intrigued by its beauty, viewers will then be inspired to find out exactly how a power plant like this works. And the Gemasolar plant is extraordinary. It uses hundreds of heliostat mirrors to focus the sun onto a giant tower at the centre that contains molten salt, which gets heated to a temperature so hot that it generates steam, and that steam spins turbines that create energy for 70,000 homes. (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

The final chapter in the book is 'Where we are not', which shows the few places on the earth where humanity has had little impact, such as the Shadegan Lagoon in Iran. “This image conveys an unfathomable sense of time,” Grant says. “When you see this lagoon, you can see how it took tens of thousands of years or more to look this way. Whereas the images of humanity’s impact on the earth – massive cities, ports or mining operations – really have only sprung up in a massive way in the last 100 years for most, the last 200 years for a few.” Many patterns in the natural world recur in unexpected places. The lagoon is fed by tributaries of rivers that are perfectly level, so it’s the properties of water that result in drainage that looks almost vascular. “We’re reminded of biology, here – these tributaries look like the roots of trees. But I’ll share this image with doctors, and they’ll say it looks like veins and arteries.” (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

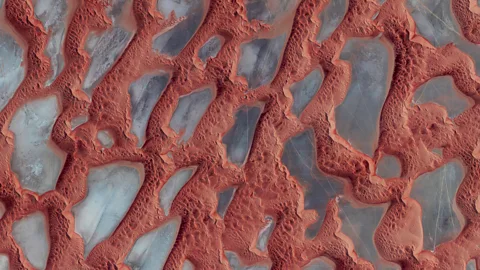

The photo of The Empty Quarter, the world’s largest contiguous sand desert, in Saudi Arabia, depicts one of the largest areas presented in the Overview book: 135 square miles (349.6 sq km). The areas that appear nearly blue were ancient lakes that over eons dried out. “When I look at it, it doesn’t look like earth,” Grant says. “It looks like Mars or another planet, and it makes you realise how large our planet is. This is a 135 square mile area, but only about a 50th of The Empty Quarter looks like this.” To give a sense once again of how sharp this image is, the camera on the Digital Globe satellite that took it would be powerful enough if placed on the ground in Los Angeles to take a picture of a beach ball on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

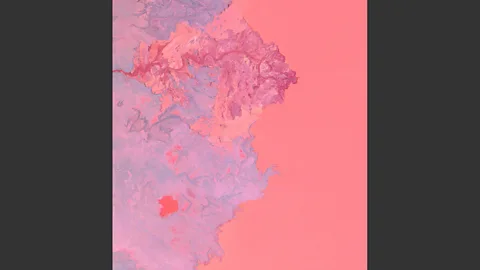

It looks like Paul Klee’s Tropical Gardening and, likewise, this landscape is entirely man-made, the result of waste products from iron ore extraction. “It looks like oil – the colours here do not occur in nature, so you know it’s an area where humans have had their hand in shaping it,” Grant says. “At the same time, when you learn what this is – highly toxic waste – you know it isn’t good. You would do anything in your power to avoid swimming in this pond. The tension between the beauty of the image and the fact that it’s actually pollution should start a conversation about the negative impact we’re having on the planet.” (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

“Like the iron ore mine tailings pond, the colours here are beautiful,” Grant says. “Visual beauty gives way to heartbreak, though, because more than 400,000 people displaced by conflict in the region already live here, and the grid pattern in the top left is a new extension to accommodate even more refugees. If you see this image on social media, can you really ‘like’ it?” Since one pixel in the photo represents 30cm on the ground, it’s essentially a matter of one pixel depicting one person, which makes you realise just how overcrowded this camp is. (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

In the Dadaab Refugee Camp we saw a version of the idea of creating a grid-like pattern within which people can live. But there’s a similar idea behind the development of planned communities in the US. Some of these planned communities, many of which were built to accommodate the mass migration of retirees to southern parts of the country, are built around patterns that can only be fully appreciated from the air. “There’s a lot of thought that goes into making planned communities work well – it’s about how functional they can be,” Grant says. “Sun Lakes comes from an era when people were fascinated with creating widespread developments that could be highly efficient, and there were unsettled places in Arizona or Florida where they could make those concepts come to life over large stretches of land.” (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

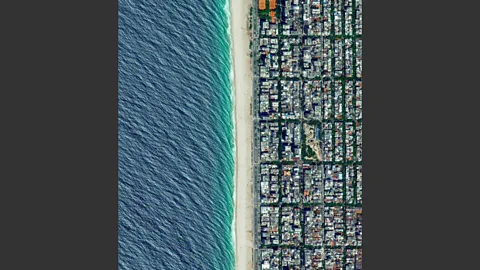

“Truly an extension of the idea that if there is a beautiful piece of land humans will do everything in their power to cover it as much as possible with their own designs,” Grant says. “This has been one of the most popular images I’ve ever posted. What better way to show man’s interaction with nature? Literally, it’s development right up to the edge. There’s the beauty of the water and then the familiar grid pattern right there. It reminds of Barnett Newman’s work, with even a centre strip – the beach – dividing the two areas.” (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

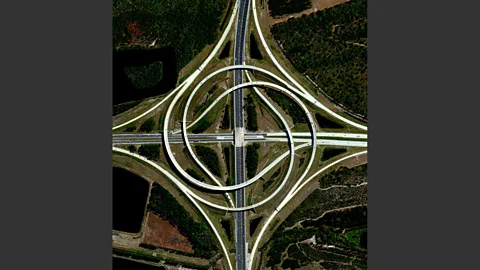

This elaborate carriageway was built on top of a forest area, so it’s extremely visible from space, unlike most highway interchange structures that are built in the middle of cities and largely overwhelmed by other infrastructure. “It reminds me of a turbine,” Grant says. “I’ve had people comment on this along the lines of ‘I’ve driven around this many times and never realised it was that cool.’” (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

Notice the tanker on the right that has shipping containers clearly visible on it. Even one ship like that is capable of carrying 300,000 tonnes of cargo – multiply that by the many ships that pass through Singapore’s port every day and you have the world’s second busiest port in terms of total tonnage. “Shipping is a vital issue, environmentally, but also economically,” Grant says. “I don’t think many people are interested in shipping or even familiar with how shipping works – but it’s amazing to see these elaborate systems that we have put in place. This is just one part of network that fuels a global economy.” (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

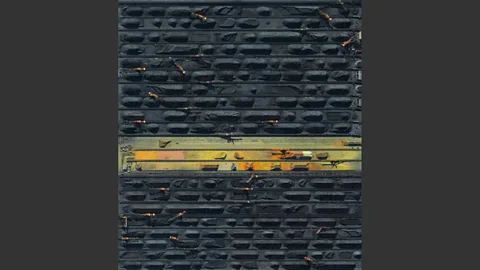

“I think of a Rothko when I see this one,” Grant says. “It’s beautiful, but you can imagine what the air would be like in a place like this. We recognise coal as one of the dirtier forms of energy we have but it is at the same time very much a reality – not just in the United States, but in China and India where it is a primary source of energy and will continue to be a primary source of energy. Here you can see it’s entirely automated – it’s a landscape we’ve created but are no longer a part of. This mining transport can operate without us.” (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)

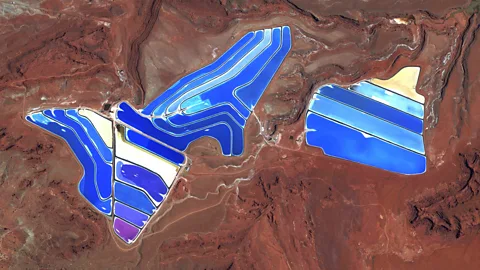

That striking, utterly artificial-looking blue looks like dollops of oil paint splattered on a canvas. When potash is extracted from the earth, it’s mixed with water; in order to get rid of the water, a blue dye is added which causes more sunlight to be absorbed and for the water in the liquid mixture to evaporate faster, leaving only dry potash behind. The white in the midst of the blue is a pool where the water has already evaporated and just the white potash crystals are left. “When you see this the next question for most of us is ‘What is potash?’” Grant says. “‘Why do we need potash?’ It’s used in fertilisers. ‘Well, why is it needed in fertilisers?’ The whole point of this project is to get people to be inquisitive, to get people to start asking questions about their world. The only way people will start acting in service of the planet is if they’re more informed about what’s really going on around them, and if they understand how their presence makes a difference. (Credit: Images (c) 2016 by DigitalGlobe, Inc)