'They’re not dolls, they're babies!': How the Cabbage Patch Kids caused a near-riot in the 1980s

Xavier Roberts' cuddly-toy business grew into a billion-dollar empire in the space of a few years. What was it about these dolls that made Christmas shoppers turn violent in 1983?

"Is that what Christmas is about? A full-grown woman taking a doll out of a child's hand."

While there had been toy crazes before, no one ever suffered a serious injury in a stampede to get their hands on a Rubik's Cube, skateboard or hula hoop. In the run-up to Christmas 1983, Cabbage Patch Kids inspired a different kind of mania in cities across the US, with one department store in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania becoming the scene of a near-riot.

As supplies of the dolls ran out, one woman broke her leg and four others were hurt, while a desperate shop manager armed himself with a baseball bat to restore calm. The cost of missing out on the must-have toy was too much for some anxious parents. By the time local mother Patti Colachino fought her way to the toy counter, the dolls were all gone. She said: "What do we tell our little girl on Christmas morning? What are we supposed to say? You've been good but Santa ran short?"

While the scenes were described by BBC newsreader John Humphrys as "the latest awful example of pre-Christmas selling hype to hit America", he noted that in Britain "the reaction's been rather more restrained and, costing as much as £24 ($31) each, perhaps that's hardly surprising". Intrepid BBC reporter Guy Michelmore was duly dispatched to London's Oxford Street, doll in hand, to gauge opinion among Christmas shoppers. The adults' views ranged from "it's all right, I suppose" to the heavily ironic "I'd rather have a doll than my very own child". It might have been an unscientific survey, but every child who was shown the doll loved it.

Britain hadn't yet come down with full-blown Cabbage Patch fever, but as the hype spread, toy shop shelves were emptying ever faster. US postal worker Edward Pennington, unable to buy a Cabbage Patch Kid for his daughter back home in Kansas, heard rumours that they might be available in London. He told the Daily Mirror newspaper: "I decided to jump on a plane, pick one up, go straight back to the airport and fly home again." At the upmarket London department store Harrods, the last nine dolls were snapped up by six air hostesses from Dallas. One of them, Barbara Ericson, told the newspaper: "It's crazy, but once our friends knew we were going to England, they all asked us to get these dolls."

The dolls came with a whimsical concept that captured the imagination of many people. The marketing spiel was that each was computer-designed to have a slightly different face; it came with its own personality profile, birth certificate and adoption form to be filled in by its new "parent". Each one bore the name of Cabbage Patch Kids creator Xavier Roberts on its bottom, signed as if it was a genuine artwork. "When I first delivered the first Cabbage Patch Kid, I never saw it as a doll – it was always a piece of art to me, being a sculptor," he told the BBC's Sally Magnusson.

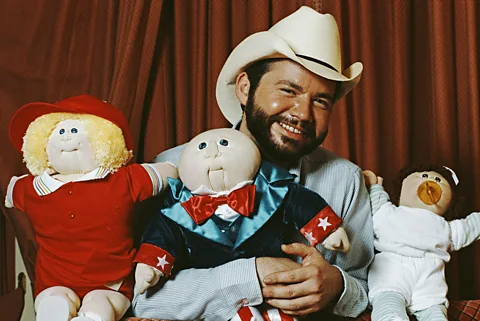

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRoberts was a 28-year-old former art student from Cleveland, Georgia, whose new fortune had allowed him to build a mansion complete with a water slide that ran from an upstairs hot tub to a swimming pool below. Just over a week after the near-riots back home, he landed in the UK to explain to baffled Brits what all the fuss was about. With his cowboy hat and gentle southern drawl, his folksy public image was more country-music star than millionaire toy tycoon. He told the BBC: "I live in the mountains of rural Georgia, and we were always told growing up that we came from a cabbage patch. So I guess I use a little bit of Mother Nature there."

Doctors and nurses delivered the 'babies'

Roberts had started out as a clay sculptor but turned to modelling children's faces out of soft fabric. He was inspired by the work of shy and retiring Appalachian folk artist Martha Nelson Thomas, who sold her distinctive Doll Babies at local craft fairs. She would end up taking legal action, and in 1984 they settled their custody battle out of court for an undisclosed amount.

Roberts was thinking a lot bigger when in 1976 he began making the handmade dolls that he originally called Little People. He came up with the ingenious idea of charging a $40 (£30) "adoption fee" for one of his signed creations, and the concept grew from there. Taking a leaf out of the Walt Disney playbook, he expanded his empire two years later by opening Babyland General Hospital, a place where people could take part in the surreal experience of swearing an oath of adoption in return for a doll.

He told the BBC: "We actually found an old clinic in Cleveland, my hometown, that we renovated and had 'doctors and nurses' working there, helping to deliver the 'babies'. And so the concept just grew, and today it's just kind of exploded." The idea was initially more popular with adults, he said, "and it wasn't until later that it really caught on for children".

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Sign up to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

The Little People concept had quickly attracted wider attention well beyond rural Georgia. Babyland even got a mention in the UK's Daily Express as early as 1980, albeit as "the kind of lunatic scheme that appeals to Americans". Still, as cynics might say, there's one born every minute, and the concept's blockbuster commercial potential was spotted by Coleco Industries, a company mainly known for its electronic toys such as the ColecoVision video game console. In 1982, the firm licensed the dolls for a mass-produced version. In a marketing masterstroke, the Little People were now called Cabbage Patch Kids.

More like this:

• How Pac-Man changed gaming – and the world

• The man who created Charlie Brown and Snoopy

• How Mickey Mouse saved Walt Disney from ruin

As the media feeding frenzy grew, the BBC sent correspondent Bob Friend to Babyland to visit the "rather more expensive brothers and sisters of the mass-produced version which is causing all the hysteria". One of the so-called nurses insisted: "They're not dolls, they're babies. Each has its own personality. They're all individuals, the same as we are." Hospital administrator Laura Meir was even more forthright. "Doll is a four-letter word that we don't use," she said. "You can go out and buy a doll that wets, cries, roller-skates, but our babies don't really do anything. They are lifelike, they're cuddly, they're warm and instead of entertaining you, the babies require your imagination."

The dolls proved so popular that they even inspired macabre bubblegum cards that became a playground phenomenon. The Garbage Pail Kids were made by trading-card firm Topps and featured grotesque cartoons designed to delight kids and horrify adults. One of the creators was Art Spiegelman, who later won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992 for his graphic novel Maus. Characters included Adam Bomb, a doll-like figure with a mushroom cloud erupting from his head, and Potty Scotty, forever wedged in a toilet. The backs of the cards carried mock permission slips granting children licence to commit anti-social acts, from skipping homework to "lying whenever you think is necessary".

One Yorkshire headteacher finally snapped when a nine-year-old stomped on a dinner lady's foot and waved his licence to misbehave. The Cabbage Patch Kids rightsholders weren't too impressed either; a trademark infringement lawsuit was settled out of court, and the Garbage Pail Kids had to be redesigned.

Are Labubu dolls the new Cabbage Patch Kids?

In the years since the Cabbage Patch Kids first sprouted, toy crazes from Tickle Me Elmo to Bratz have inspired fevered shopping battles. Earlier this year, there were even tussles in London over Labubu dolls. Their maker, Pop Mart, paused selling its quirky monster collectibles in shops after reports that customers were fighting over them. Labubu fan Victoria Calvert said she witnessed chaos in one store. "It was just getting ridiculous to be in that situation where people were fighting and shouting, and you felt scared," she told the BBC.

As unpleasant as such situations are, though, they can also be highly profitable. Xavier Roberts told the BBC that, by the end of 1983, he and Coleco Industries were on course to be "adopting out over two-and-a-half-million Cabbage Patch Kids". Asked how much money he had made from the dolls, he smiled and admitted: "A lot. A lot of greens."

--

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebookand Instagram.