Directors’ cuts: The beauty parlour on screen

Scenes in beauty salons crop up all the time on film – but is there more to them than hair and make-up? Lindsay Baker finds out.

It’s a place where all kinds of women gather: identities are transformed, intimate secrets spilled and jokes shared. The beauty salon is perhaps the best location ever invented for the purpose of female bonding. So it’s no wonder that it also makes a popular cinematic setting. And just as the men’s barber shop is an iconic movie location – think Get Shorty, the Untouchables, Sweeney Todd, to name but a few – so the scenes set in beauty shops are some of cinema’s most memorable moments.

The 1939 Joan Crawford movie The Women was probably the earliest example of the salon scene, and numerous others followed, notably 1975 comedy-drama Shampoo. Arguably, though, the heyday of beauty-shop cinema was the 1980s. It was, after all, a time of big hair and bold make-up.

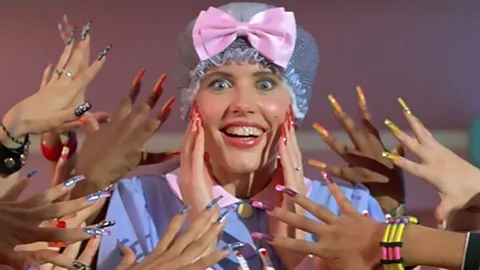

John Waters’ kitsch comedy musical Hairspray, re-made in 2007, is among the ‘80s salon gems, then there is the ludicrous-but-fun Earth Girls are Easy, largely set in a beauty parlour named Curl Up and Dye. Starring Geena Davis as Valley girl manicurist Valerie, the movie features a choreographed, all-singing, all-dancing salon-makeover montage scene (Grease’s Beauty School Dropout dream sequence was a precursor to the genre). Valerie is given a complete hair-and-makeup re-working by her friend, and the Day-Glo-furred aliens (including Jeff Goldblum) are treated to a full body shave and makeover, so that they can pass as human.

Skin deep

The writer and academic Tiffany Gill, author of Beauty Shop Politics: African American Women's Activism in the Beauty Industry, has investigated the empowering role of the salon. “I think the personal act of beautification combined with the opportunity to gather with other women and where you are essentially a captive audience allows for the free sharing of ideas and information,” she tells BBC Culture. “And for black women who have historically been vilified for having a hair texture different than white Europeans, beauty shops have become spaces where black women cultivate their own beauty on their own terms.”

“Placing a movie scene in a beauty shop allows the filmmaker to gather women together in a fun and believable way and get a wide variety of voices and opinions – often with a comedic twist,” says Gill, pointing to the film Beauty Shop with Queen Latifah, “where the salon was often a site of exchange between the stylists and their clients where they discussed romantic relationships, child-rearing, and popular culture.” And Soul Food, “where family and financial conflict was played out.” And Waiting to Exhale, “when the character Bernadine, played by Angela Bassett, decided to visit her friend's salon for moral support and a dramatic hair transformation after learning of her husband's infidelity… Beauty shop conversations in film, and in real life, cover a wide range of topics from the sublime to the ridiculous.”

We get a sense of both – and an explosion of ‘80s colour, accessories and hair – in the classic comedy-drama Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), in which suburban housewife Roberta (Rosanna Arquette) is enthralled by the cool, independent, confident Susan (Madonna). Transformation is the theme of the film, which tells how Roberta, with her perfect-seeming but ultimately boring life, finds her true identity and sense of self by following in the exciting footsteps of Susan in downtown Manhattan. And it is the beauty-salon scene from which the action unfurls – while under the retro hair dryer, Roberta spots the personal ad from Jim ‘Desperately seeking Susan’. From that moment, the path is set for her entanglement in their world and her eventual self-discovery.

‘Friendship and solidarity’

Roberta’s path to empowerment is rather different from the archetypal duckling-to-swan transformation, which is of course nothing new as a narrative arc (think Cinderella and Pygmalion). This cinematic trope has endured and been adapted for each new era, though it doesn’t always work. Some critics were disappointed by the makeover of Allison at the end of Breakfast Club, a previously strong female character turning sappy. The geek-to-chic makeover continues to be popular though, and has tended to crop up in teen many movies – sometimes, though not always, in a beauty-salon context – Mean Girls, Clueless, She’s All That, to name but a few.

Arguably though, the quintessential beauty-parlour film is another ‘80s classic, Steel Magnolias, about the inter-connecting lives of the staff and clients of a salon in Louisiana. Many of the central scenes take place in the parlour owned by Dolly Parton’s character, Truvy, and the film’s story encompasses a range of distinct characters from different backgrounds, each supporting the others in their own way. The group of women crosses boundaries of class and age, and home truths, intimacies and vulnerabilities are shared across the generations. As she stands on the porch of her salon with her young assistant (played by Daryl Hannah), Truvy drily reflects on the ageing process: “Honey, time is marching on and it is marching all over my face.”

Steel Magnolias’ strong ensemble cast is female, and the men in the film rather marginal – it is a quintessential movie of friendship and solidarity among women. As Yvonne Tasker puts it in her book Working Girls: Gender and Sexuality in Popular Cinema: “Paradoxically, the inclusion of men [in Steel Magnolias] as characters, functions if anything to emphasise their marginality. Men are the cause of narrative problems which we watch women dealing with in these movies, an inversion of the countless narratives in which women bring chaos into men’s worlds.” Unsurprisingly perhaps, Steel Magnolias – along with most other movies based around or featuring beauty salons – easily passes the Bechdel Test – the measuring rule that assesses gender portrayal in a film by its female-to-female dialogue.

It is the sheer silliness and life-affirming energy of the best beauty-salon scenes that, although frivolous, make them memorable. In Legally Blonde, the scenes set in Neptune’s Beauty Nook provide the perfect counterpoint to Elle’s initial law-school experience. The earthy comedy of the salon scenes show Elle (Reese Witherspoon) in her natural habitat, warm, charismatic, strong, inclusive. In one scene Elle advises her best friend Paulette, who works in the salon, to be more confident and to flirt with a man she likes, then proceeds to demonstrate the ‘bend-and-snap’ move – in which you bend down to reach for something, then snap up with a smile. Soon all the salon clients – of all shapes and sizes – are joining in, encouraged by Elle’s infectious enthusiasm. As Paulette’s male colleague exclaims when he walks in: “Oh, the bend and snap! Works every time!”

Empowering, transformative, just plain absurd – the salon has been the perfect location for some great cinematic moments over the past few decades. And as a classic movie setting, the beauty parlour has proved to be resilient so far, adjusting itself as society and tastes mutate. But what now?

“What's interesting to me is that beauty shop scenes seem to be diminishing in films,” says Gill. “Now that many African American women are wearing their hair natural, and with the increased popularity of YouTube and other online spaces as a primary vehicle for women to learn how to care for hair and beauty, I wonder what will happen to the beauty shop in film.” But perhaps, like a good makeover, it will adapt and transform.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.