How mad hatters took over fashion

Millinery masterpieces are no longer just for Royal Ascot and the Kentucky Derby. Hats are the perfect accessory for the social media era, Lindsay Baker writes.

As if the dramatic headgear worn by Pharrell Williams and Lady Gaga wasn’t proof enough that extravagant hats are on the rise, take a look at New York Fashion Week and its Spring/Summer 2015 collections. Towering straw creations at Donna Karan’s show, a dizzying array of extreme, eccentric styles at Thom Browne – the sheer showmanship of the millinery on display was undeniable.

These show-stopping creations were the work of British milliner Stephen Jones, who is also the curator of Headonism, a London Fashion Week showcase in association with Wedgwood that champions emerging British millinery. Jones, who has been at the epicentre of millinery for several decades, has clients including Dita Von Teese, Mick Jagger and Rihanna and has worked with an array of designers from Zandra Rhodes and Marc Jacobs, to Giles Deacon, John Galliano and Rei Kawakubo.

The current resurgence of flamboyant hats must feel familiar to Jones, who came to prominence in the 1980s when he brought the fantastical, outlandish spirit of London’s clubland to his designs. “I think for us the Blitz era was fantasy,” Jones tells BBC Culture. “It might have been subversive but we didn’t think so. Other people got upset by it and said we were ‘parading like peacocks’, but for us, fashion was our drug. At that time millinery was seen as something very esoteric and quite archaic,” recalls Jones. “I reintroduced it for a young audience. People loved being transformed and transported by something wonderful on their heads.”

Jones points to iconic moments in hat design as inspirational – Salvador Dalí’s 1937 collaboration with Elsa Schiaparelli is one of his all-time favourites. The surrealist ‘shoe hat’ was ground-breaking, absurdist and, well, bonkers. The British particularly love hats, says the milliner, and points to the inventiveness of the wartime ‘make-do-and-mend’ ethos, with stylish, forward-thinking women “making a turban out of their husband’s waistcoat”.

Yet for all its eccentric, outlandish moments, millinery also has a venerable heritage that is all about conformity and formality: hats have long been worn to comply with sober dress codes at church weddings, garden parties or other formal events. In Jones’s view the national love of hats is largely down to the Queen and the late Queen Mother, “the patron saints of hatters”, and certainly over the centuries hats have acted as cultural and class signifiers.

‘The Season’, when the social elite hold their events, has traditionally been a time for hat wearing – no more so than Royal Ascot, in particular Ladies Day, a peculiarly British pageant with strict sartorial rules. Hats must span four inches on the crown of the head, and revealing dresses are not permitted. For Jones, though, Ascot is less about dress codes and class boundaries, and more about fun and flamboyance for everyone: “Since the 1800s race meetings and particularly Ascot have been about dressing up, showing your finery and having a good time, whatever part of society you come from and no matter how much money you have. There are records even in the 19th Century of duchesses being tipsy on fine champagne and farm girls rollicking about, egged on by pale ale.”

Hat tricks

For Keely Hunter hats are about “always looking forward”. She is one of the emerging milliners being showcased at Headonism this year, and has created sculptural, futuristic styles for the likes of singer Paloma Faith. Inspired by architecture and engineering, she uses hi-tech heating and blending techniques to create her felt and vacuum-formed plastic creations. She would like to see fabulous hats move into the realm of more everyday accessories, on par with “a fantastic pair of shoes or a lovely belt”.

Björk, Lady Gaga and designers such as enfant terrible Gareth Pugh (who has collaborated with milliner Noel Stewart) have helped push the boundaries, says Hunter. And she also points to the late Isabella Blow as a hat game changer. The anti-establishment yet aristocratic fashion muse brought headgear into the spotlight in the 1990s, through her patronage of acclaimed Irish milliner Philip Treacey and her own flamboyant, behatted appearance. “And the Royal wedding [of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in 2011] helped put hats on the map,” adds Hunter. “Though my hats aren’t that style.”

Social media is another factor in the resurgence of millinery, of course. It helps designers promote themselves directly, says Hunter: “There’s no hierarchy any more. Celebrities were totally unreachable before, but now the channels of communication are open.”

And with the look-at-me culture of social media so prevalent, it was only a matter of time before the hat took centre stage. In his book Hats: An Anthology, Stephen Jones writes, “Everyone from showgirls to dictators knows that by wearing a hat they will be the centre of attention... They confer a sense of presence and poise to the wearer that, in my mind cannot be achieved through clothing or other accessories... The hat’s impact is a synthesis of who the person is and who they want to be. When the two are blended together it becomes a great personal signature.”

As Awon Golding, another emerging milliner who is showcasing her work at Headonism, tells BBC Culture: “People are looking to make a statement on social media, and to stand out. And what your clothes say about you has become more important, with a hashtag pinpointing exactly the statement you’re making.” And taking it one step further, for those who want to make a “completely unique statement”, Golding runs workshops where budding hat designers, “aged 16 to 70”, can create their own handmade headpiece or fascinator. “Crafting in general is very popular at the moment, and I think it’s an answer to mass-produced fashion.”

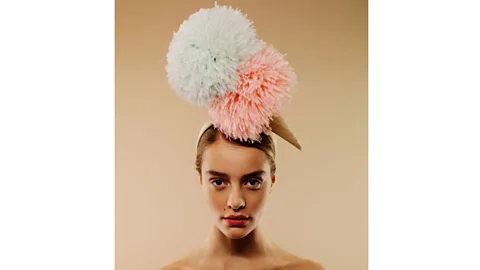

One of Golding’s most extravagant creations – her extraordinary double-scoop-ice-cream hat created with ostrich feathers – gained attention on Instagram, when HardCandy, a Shanghai blogger, posted an image of it. So what is the wearer of this hat saying, in Golding’s opinion? “The statement is: ‘I have a sense of humour, I’m not a boring person, I’m having fun.’ That hat is a light piece, it puts a smile on your face.”

So do you have to be a flamboyant extrovert to wear hats? Not necessarily, argues Golding, they can also disguise the wearer or make them anonymous: “They can be very demure – veiling or masking your face and creating a certain mood. A wide-brimmed hat creates a shadow over the face and highlights just the lips.” Or, like icons of cool Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo in their classic, severe, androgynous berets and cloches, the statement may be not so much ‘Look at me’ as the now less frequently expressed ‘back off’ or ‘I want to be alone’.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.