Sight is our dominant sense. Almost all animals can see. In fact, 86 per cent of animal species have eyes. And what’s interesting is that at the molecular level every eye in the world works in the same way.

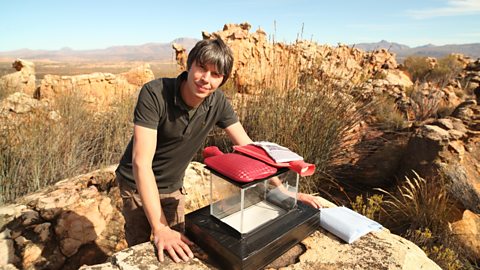

In order to form an image of the world, then obviously the first thing you have to do is detect light. And I have a sample here of the molecules that do that, that detect light in my eye. It’s actually specifically the molecule that’s in the black and white receptor cells in my eyes, the rods. It’s call Rhodopsin. And the moment I expose this to light you’ll see an immediate physical change.

There you go. Did you see that? It was very quick. It came out very pink indeed and it immediately went yellow.

This subtle shift in colour is caused by the rhodopsin molecule changing shape as it absorbs the light.

In my eyes what happens is that change in structure triggers an electrical signal which ultimately goes all the way to my brain, which forms an image of the world. It’s this chemical reaction that’s responsible for all vision on the planet.

Closely related molecules lie at the heart of every animal eye. And that tells us that this must be a very ancient mechanism.

To find its origins, we must find a common ancestor that links every organism that uses rhodopsin today. We know that common ancestor must have lived before all animals’ evolutionary lives diverged. But it may have lived at any time before then.

So what is that common ancestor? Well here’s where we approach the cutting edge of scientific research. The answer is that we don’t know for sure, but a clue might be found here.

In these little green blobs which are actually colonies of algae, algae called Volvox.

We have very little in common with algae. We’ve been separated in evolutionary terms for over a billion years. But we do share one surprising similarity.

These volvox have light-sensitive cells that control their movement. And the active ingredient in those cells is a form of rhodopsin so similar to our own that it’s thought they may share a common origin.

What does that mean? Does it mean that we share a common ancestor with the algae, and in that common ancestor the seeds of vision can be found?

To find a source that may have passed this ability to detect light to both us and the algae, we need to go much further back down the evolutionary tree to organisms like cyanobacteria. They were among the first living things to evolve on the planet, and it’s thought that the original rhodopsin may have developed in these ancient photosynthetic cells.

So the origin of my ability to see may have been well over a billion years ago, in an organism as seemingly simple as a cyanobacterium.

The basic chemistry of vision may have been established for a long time, but it’s a long way from that chemical reaction to a fully functioning eye that can create an image of the world.

The eye is a tremendously complex piece of machinery built from lots of interdependent parts, and it seems very difficult to imagine how that could have evolved in a series of small steps. But actually we understand that process very well indeed. I can show you by building an eye.

The first step in building an eye would be to take some kind of light-sensitive pigment, rhodopsin, for example, and build it onto a membrane. So imagine this is such a membrane with the pigment cells attached.

Then immediately you have something that can detect the difference between dark and light. But the disadvantage, as you can see, is that there’s no image formed at all. It just allows you to tell the difference between light and dark.

But you can improve that a lot by adding an aperture, a small hole in front of the retina. So this is a movable aperture, just like the type of thing you’ve got in your camera. Now, see. The image gets sharper. But the problem is that in order to make it sharper, you have to narrow down the aperture, and that means that you get less and less light. So this eye becomes less and less sensitive. So there’s one more improvement that nature made, which is to replace the pinhole, the simple aperture, with a lens.

Look at that. A beautifully sharp image.

The lens is the crowning glory of the evolution of the eye. By bending light onto the retina, it allows the aperture to be opened, letting more light into the eye, and a bright detailed image is formed.

Video summary

Professor Brian Cox shows the stages of the evolution of the eye, from a primitive light sensitive spot, to a complex mammalian eye.

Almost all animal life can see (96% of species have an eye), and at a molecular level, every eye in the world works in the same way. At the heart of all vision is a light sensitive pigment called rhodopsin.

This clip is from the series Wonders of Life.

Teacher Notes

As a follow-up activity, make a pinhole camera from black card then investigate how changing the aperture size and adding a lens improves the quality of the image.

Pupils could produce a flow chart showing the evolution of the eye in a series of small steps, from simple light sensitive cells in volvox, to the camera eye found in modern animals such as humans.

This clip will be relevant for teaching Biology at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and SQA National 3/4/5 in Scotland.

Bacteria and the development of an oxygen rich atmosphere. video

Professor Brian Cox explains how the Earth developed an oxygen rich atmosphere due to organisms called Cyanobacteria.

Conservation of energy. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the first law of thermodynamics. He describes how energy is always conserved, never created or destroyed.

How has life on Earth become so varied? video

Professor Brian Cox explores how life on Earth is so varied, despite us all being descended from one organism, known as LUCA. He examines how cosmic rays drive the mutations that create evolution.

Lemurs: Evolution and adaptation. video

Professor Brian Cox visits Madagascar to track down the rare aye-aye lemur, and see how it is perfectly adapted to suit its surroundings.

Jellyfish and photosynthesis. video

Professor Brian Cox sees photosynthesis in action, investigating a unique type of jellyfish that have evolved to carry algae within their bodies and feed off the glucose the plants create.

The arrival of water on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox describes the similarities between isotopes of water on comets and our planet and suggests that the water in the oceans may have come from asteroids.

The origins of life on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox explains that in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, energy is released in the presence of organic molecules.

Evolution of hearing. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the evolution of the mammalian ear bones, the malleus, incus and stapes by using a flicker-book to show how the gill arches of jawless fish altered in size and function.

Evolution of the senses. video

Professor Brian Cox compares the way that protists sense and react to their environment with the action potentials found in the nerves of more complex life.

Gravity, size and mass. video

An explanation of how forces including gravity affect organisms. Professor Brian Cox explains that as size doubles, mass increases by a factor of eight.

Size and heat. video

Professor Brian Cox explores the relationship between an organism's body size and its metabolic rate.