The story of how we developed our ability to hear is one of the great examples of evolution in action.

Because the first animals to crawl out of the water onto the land would have had great difficulty hearing anything in their new environment.

These are the Everglades, a vast area of swamps and wetlands that has covered the southern tip of Florida for over 4,000 years.

Through the creatures we find here, like American alligator, a member of the crocodile family, we can trace the story of how our hearing developed as we emerged onto the land.

These are the smallest three bones in the human body. They’re called the malleus, the incus and the stapes, and they sit between the eardrum and the entrance to your inner ear, to the place where the fluid sits.

The bones help to channel sound into the ear through two mechanisms.

First, they act as a series of levers, magnifying the movement of the eardrum. And second, because the surface area of the eardrum is 17 times greater than the footprint of the stapes, the vibrations are passed into the inner ear with much greater force.

And that has a dramatic effect. Rather than 99.9 per cent of the sound energy being reflected away, it turns out that with this arrangement, 60 per cent of the sound energy is passed from the eardrum into the inner ear.

Now, this setup is so intricate and so efficient that it almost looks as if these bones could only ever have been for this purpose. But in fact you can see their origin if you look way back in our evolutionary history.

Back around 530 million years, to when the oceans were populated with jawless fish called agnathans. They’re similar to the modern lamprey. Now, they didn’t have a jaw, but they had gills supported by gill arches.

Now, over a period of around 50 million years the most forward of those gill arches migrated forward in the head to form jaws. And you see fish like these, the first jawed fish, in the fossil record around 460 million years ago. And there at the back of the jaw there is that bone, the hyomandibula, supporting the rear of the jaw.

Then, around 400 million years ago the first vertebrates made the journey from the sea to land. Their fins became legs. But in their skull and throat other changes were happening. The gills were no longer needed to breathe the oxygen in the atmosphere, and so the faded away and became different structures in the head and throat, and that bone, the hyomandibular, became smaller and smaller until its function changed. It now was responsible for picking up vibrations in the jaw and transmitting them to the inner ear of the reptiles. And that is still true today of our friends over there.

But even then the process continued…

Around 210 million years ago, the first mammals evolved, and unlike our friends the reptiles here, mammals have a jaw that’s made of only one bone. A reptile’s jaw is made of several bones fused together. So that freed up two bones, which moved and shrank and eventually became the malleus, the incus and the stapes. So this is the origin of those three tiny bones that are so important to mammalian hearing…

He’s quite big isn’t he?

Video summary

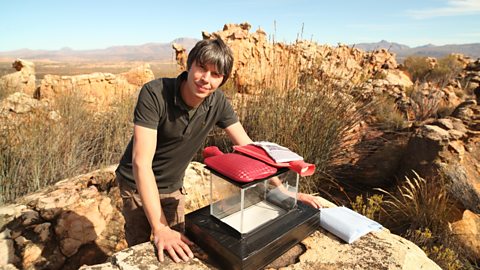

Professor Brian Cox explains the evolution of the mammalian ear bones, the malleus, incus and stapes.

He uses a flip-book animation to show how the jaw bones of basal reptiles migrated back into the skull to form the tiny bones of the middle ear.

This clip is from the series Wonders of Life.

Teacher Notes

This clip could be used to show how the three smallest bones in the body work to help us to hear. Could be used in association with a larger ear model where the students can see the use of these bones in the mechanism of hearing.

They could work in a group to act out how the sound waves enter into the ear and how the ear in turn interprets these waves into sound signals the brain uses.

This clip could be used to exemplify how species have evolved over the period of a number of years. For example, the flipchart used in the clip shows how scientists believe the three bones in the ear evolved.

However, this can also be used to show how we can use this information to trace back family ancestry, using this in conjunction with the fossil evidence such as those for horses for example.

This clip will be relevant for teaching Biology at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and SQA National 3/4/5 in Scotland.

Bacteria and the development of an oxygen rich atmosphere. video

Professor Brian Cox explains how the Earth developed an oxygen rich atmosphere due to organisms called Cyanobacteria.

Conservation of energy. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the first law of thermodynamics. He describes how energy is always conserved, never created or destroyed.

How has life on Earth become so varied? video

Professor Brian Cox explores how life on Earth is so varied, despite us all being descended from one organism, known as LUCA. He examines how cosmic rays drive the mutations that create evolution.

Lemurs: Evolution and adaptation. video

Professor Brian Cox visits Madagascar to track down the rare aye-aye lemur, and see how it is perfectly adapted to suit its surroundings.

Jellyfish and photosynthesis. video

Professor Brian Cox sees photosynthesis in action, investigating a unique type of jellyfish that have evolved to carry algae within their bodies and feed off the glucose the plants create.

The arrival of water on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox describes the similarities between isotopes of water on comets and our planet and suggests that the water in the oceans may have come from asteroids.

The origins of life on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox explains that in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, energy is released in the presence of organic molecules.

Evolution of sight. video

Professor Brian Cox shows the stages of the evolution of the eye, from a primitive light sensitive spot, to a complex mammalian eye.

Evolution of the senses. video

Professor Brian Cox compares the way that protists sense and react to their environment with the action potentials found in the nerves of more complex life.

Gravity, size and mass. video

An explanation of how forces including gravity affect organisms. Professor Brian Cox explains that as size doubles, mass increases by a factor of eight.

Size and heat. video

Professor Brian Cox explores the relationship between an organism's body size and its metabolic rate.