I want to show you why our world is the only habitable planet we know of anywhere in the universe. Now, the answer depends on the presence of a handful of precious ingredients that make our world a home.

One of the most important of which is a substance vital to all known forms of life. Water.

Our planet is the only one we know with a surface still drenched in liquid water.

The story of how each drop ended up here has been hard to fathom. Largely because it happened so long ago there’s very little direct evidence.

But in the Yucatan jungle in Mexico, clues to how it turned up can still be found.

The landscape here is peppered with deep wells of water, called cenotes.

Every civilisation on the Yucatan, be it the modern Mexicans or the Mayans, had to get their water from the cenotes. And I’ve got a map, a completely unbiased map of the larger cenotes here which I’m going to overlay on the Yucatan.

And look at that: the lie in a perfect arc, centred around a very particular village, which is there, and it’s called Chicxulub. Now, to a geologist there are very few natural events that can create a structure, such a perfect arc as that.

All the evidence points to just one explanation.

We’re looking at what’s left of a gigantic asteroid strike.

One that wiped out three quarters of all plant and animal species when it hit the Earth 65 million years ago.

You may think that impacts from space are a thing of the past, a thing that only happened to the dinosaurs, but that’s not true either. About 55 million kilograms of rock hits the Earth every year, and around two per cent of that is water.

This hints that at least some of Earth’s water arrived from space.

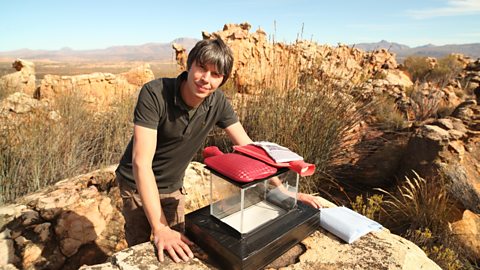

Late in 2010, these glimpses of comet Hartley 2 arrived back on Earth. They were sent by NASA’s deep impact probe.

From the comet’s surface dust and ice spray into space. Analysis of this water showed that it has a very similar chemical composition to the water in our oceans.

This was the first firm evidence that icy comets must have contributed to the formation of our world’s oceans.

Earth began life as a molten hell. Its internal heat drove off any trace of moisture. But soon the planet cooled and it’s thought that water brought by comets condensed, contributing to the creation of the first clouds. Then, 4.2 billion years ago, a deluge the like of which the solar system has never seen before or since rained down. Forming our oceans.

As a liquid, water molecules are held together by hydrogen bonds. And breaking these bonds and turning liquid into gas takes a lot of energy. In other words, hydrogen bonds are what makes water’s boiling point high. High enough to have allowed it to remain on the surface of the Earth as a liquid to the present day.

So from quite early in its history, our home has been able to hang on to this most vital of ingredients.

Any its presence made possible the arrival and persistence of life.

Video summary

Water is the molecule that makes our world habitable, and it's vital to all known forms of life.

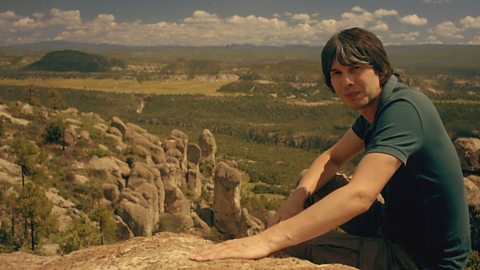

Professor Brian Cox visits the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico to see the evidence of a massive asteroid impact which wiped out nearly three quarters of life on Earth.

But despite these being an incredibly destructive force, asteroid collisions may have actually been important in bringing the first water to our planet.

This clip is from the series Wonders of Life.

Teacher Notes

As a follow-up activity, research the boiling point of a large number of substances and plot a graph of relative molecular mass against boiling point to highlight the special properties of water.

Investigate the properties of water including boiling point, melting point, density (at different temperatures), surface tension, specific heat capacity and its properties as a solvent. Relate these to water being a polar molecule that forms hydrogen bonds and explain how each of these properties is important in the maintenance of life.

Put all of the information together into a water fact file and include further information such as hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules.

This clip will be relevant for teaching Chemistry at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and SQA National 3/4/5 in Scotland.

Bacteria and the development of an oxygen rich atmosphere. video

Professor Brian Cox explains how the Earth developed an oxygen rich atmosphere due to organisms called Cyanobacteria.

Conservation of energy. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the first law of thermodynamics. He describes how energy is always conserved, never created or destroyed.

How has life on Earth become so varied? video

Professor Brian Cox explores how life on Earth is so varied, despite us all being descended from one organism, known as LUCA. He examines how cosmic rays drive the mutations that create evolution.

Lemurs: Evolution and adaptation. video

Professor Brian Cox visits Madagascar to track down the rare aye-aye lemur, and see how it is perfectly adapted to suit its surroundings.

Jellyfish and photosynthesis. video

Professor Brian Cox sees photosynthesis in action, investigating a unique type of jellyfish that have evolved to carry algae within their bodies and feed off the glucose the plants create.

The origins of life on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox explains that in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, energy is released in the presence of organic molecules.

Evolution of hearing. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the evolution of the mammalian ear bones, the malleus, incus and stapes by using a flicker-book to show how the gill arches of jawless fish altered in size and function.

Evolution of sight. video

Professor Brian Cox shows the stages of the evolution of the eye, from a primitive light sensitive spot, to a complex mammalian eye.

Evolution of the senses. video

Professor Brian Cox compares the way that protists sense and react to their environment with the action potentials found in the nerves of more complex life.

Gravity, size and mass. video

An explanation of how forces including gravity affect organisms. Professor Brian Cox explains that as size doubles, mass increases by a factor of eight.

Size and heat. video

Professor Brian Cox explores the relationship between an organism's body size and its metabolic rate.