Our natural world is spectacularly diverse.

From the tiniest bacteria to the tallest trees, and the most obscure looking animals. So how has life become so varied?

We know that every living thing on the planet today, so every piece of food you eat, every animal you've seen, everyone you've ever known, or will know, in fact, every living thing that will ever exist on this planet was descended from one speck.

We call it the Last Universal Common Ancestor, or LUCA. So, just as the universe had its origin at the Big Bang, all life on this planet had its origin in that one moment.

Now, we don't know what LUCA looked like. We don't know precisely where it lived, or how it lived, but we do know this: if you start to trace my ancestral line back to my parents, to their parents, to their parents, to their parents, all the way back through geological timescales, over hundreds of thousands of millions and billions of years there will be an unbroken line all the way back from me to LUCA.

We know that because every living thing on the planet today shares the same biochemistry.

We all have DNA. It's made of the same bases: A, C, T, and G. They code for the same amino acids. Those amino acids build the same proteins, which do very similar jobs, whether you're a plant, a bacterium, or a bipedal hominid like me.

So, all life uses the same fundamental biology.

Those four bases, A, C, G, and T, which code for just 20 amino acids, which in turn build each and every one of life's proteins.

Be you bacteria, plant, bug, or beast, your design comes from your DNA.

So it's this molecule that must hold the key to understanding why life today is so diverse.

We now know the answer to the question, "Why is life on earth so varied?" is actually the answer to the question, "Why is the DNA molecule itself so varied?"

What are the natural processes that cause the structure of DNA to change? Well, part of the answer, actually, doesn't lie on Earth at all.

It lies up there, amongst the stars, and I can show you what I mean using this, which is a cloud chamber A piece of apparatus that has a unique place in the history of physics.

I'm gonna cool it down dry ice, frozen carbon dioxide, just below -70 degrees Celsius.

Put the top on.

WHISTLING

Hear that?

That's the metal at the bottom of the tank cooling down very rapidly to -70.

The cloud chamber works by having a super saturated vaper of alcohol inside the chamber. Plenty on there.

Now, I wanna get that alcohol, I wanna boil it off, to get the vapor into the chamber, so I'm gonna put a hot water bottle on top. I mean, this is the first genuine particle physics detector. It's the piece of apparatus that first saw anti-matter, and it really does consist only of a fish tank some alcohol, a bit of paper, and a hot water bottle.

There, look at that. You see that cloud, that vapor trail. That's a cosmic ray. That was initiated by a particle, probably a proton that hit the Earth's atmosphere. Now, imagine if one of those hits the DNA of a living thing. What that will do is cause a mutation. That mutation may be detrimental, or, very, very occasionally, it might be beneficial.

Mutations are an inevitable part of living on a planet like Earth. They're the first hint at how DNA and the genes that code for every living thing change from generation to generation. Mutations are the spring from which innovation in the living world flows. But cosmic rays are not the only way in which DNA can be altered.

There's natural background ration from the rocks, there's the action of chemicals, and free radicals. There can be errors when the code is copied, and then all those changes can be shuffled by sex. And indeed whole pieces of the code can be transferred from species to species.

So, bit by bit, in tiny steps, from generation to generation, the code is constantly randomly changing.

It's these changes to DNA, are billions of years, that have led to the evolution of new life forms, and driven the magnificent diversity we see today.

Video summary

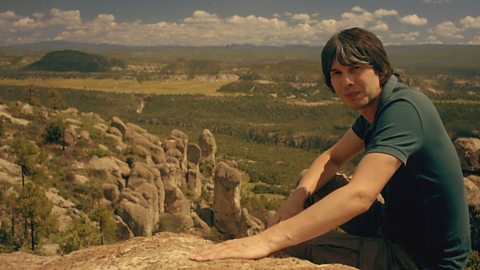

Professor Brian Cox explores how life on Earth has become so varied.

Our natural world is spectacularly diverse, from the tiniest bacteria, to the tallest trees. But every living thing on the planet is descended from one organism we call the Last Universal Common Ancestor, or LUCA.

We know this because all life shares the same fundamental biochemistry; our DNA is built from the same four organic bases. So what created the abundance of life forms?

Using a cloud chamber to observe cosmic rays, he explains how they’re an important source of mutation that drives the evolution of life.

This clip is from the series Wonders of Life.

Teacher Notes

Challenge students to the evidence that we have for how life began on Earth. Challenge them to order the evidence as to what they find the most persuasive and why.

This clip will be relevant for teaching Biology at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and SQA National 3/4/5 in Scotland.

Bacteria and the development of an oxygen rich atmosphere. video

Professor Brian Cox explains how the Earth developed an oxygen rich atmosphere due to organisms called Cyanobacteria.

Conservation of energy. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the first law of thermodynamics. He describes how energy is always conserved, never created or destroyed.

Lemurs: Evolution and adaptation. video

Professor Brian Cox visits Madagascar to track down the rare aye-aye lemur, and see how it is perfectly adapted to suit its surroundings.

Jellyfish and photosynthesis. video

Professor Brian Cox sees photosynthesis in action, investigating a unique type of jellyfish that have evolved to carry algae within their bodies and feed off the glucose the plants create.

The arrival of water on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox describes the similarities between isotopes of water on comets and our planet and suggests that the water in the oceans may have come from asteroids.

The origins of life on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox explains that in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, energy is released in the presence of organic molecules.

Evolution of hearing. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the evolution of the mammalian ear bones, the malleus, incus and stapes by using a flicker-book to show how the gill arches of jawless fish altered in size and function.

Evolution of sight. video

Professor Brian Cox shows the stages of the evolution of the eye, from a primitive light sensitive spot, to a complex mammalian eye.

Evolution of the senses. video

Professor Brian Cox compares the way that protists sense and react to their environment with the action potentials found in the nerves of more complex life.

Gravity, size and mass. video

An explanation of how forces including gravity affect organisms. Professor Brian Cox explains that as size doubles, mass increases by a factor of eight.

Size and heat. video

Professor Brian Cox explores the relationship between an organism's body size and its metabolic rate.