Ever since life began, it's been diversifying.

As conditions change, so does life. It evolves…

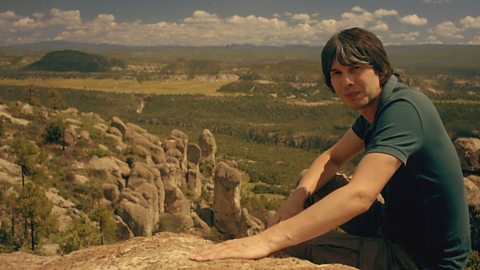

Evolution is driven by a process called natural selection. And there's no better place to see how it works 'than in the forests of Madagascar.

There, at the top of the tree, is an Indri, which is the largest lemur in Madagascar.

The reason it's thought that we find lemurs here in Madagascar, in Madagascar alone, is because there are no simians, there are no chimpanzees, none of my ancestral family dating back tens of millions of years to out compete them.

So, what's thought happened is that, around 65 million years ago, one of the lemurs ancestors, managed to sail across the Mozambique Channel, and landed here.

There were none of those competitors here, and so the lemurs have flourished ever since.

There are now over 90 species of lemur, or sub-species, in Madagascar. No species of my linage, the simians.

LEMUR CALLS

Over a vast sweep of time, 'the lemurs have diversified to fill all manner of different habitats. From the arid, spiny forests of the south, to the rocky canyons in the north.

There is something about this island 'that is allowing the lemur's DNA to change in the most amazing ways. We're on the hunt for an aye-aye, 'the most closely related of all the surviving lemurs 'to their common ancestor.

Scientist 1:

Right there.

Scientist 2:

See the body move?

Brian:

Oh yeah! Yes, yeah.

The team want to attach radio collars onto the aye-ayes so they can track their movements. But first, they need to find and sedate them, 'which is an incredibly tricky business. I mean, how you get a clean shot in this, I have no idea.

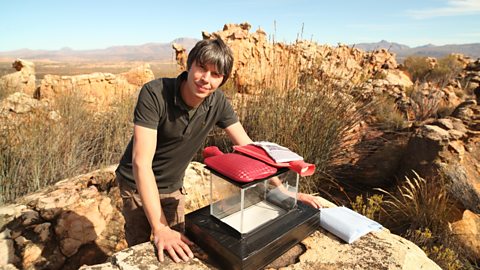

Here is the aye-aye that was tranquilised last night. They finally got her about half an hour after we left.I think it was probably because we were disturbing her. Apparently, as soon as we'd gone, she came down the tree, and she was tranquilised, and as you can see, she's really well sedated now.

Which is fortunate for me, because she has certain adaptations that I wouldn't like to be deployed. You can see there, the teeth, the teeth are very unusual for a primate.

In fact, unique, because they carry on growing, so she's much more like a rodent in that respect, and that's so she can gnaw into wood. See, aye-ayes have filled a unique niche on Madagascar.

It's a niche that's filled by woodpeckers in many other areas of the world.

What she does is she feeds on grubs and bugs inside trees, and to do that she has several unique adaptations of which the teeth are one. The most startling is this central finger here. It's bizarre. It's got a ball and socket joint, for a start, so it has complete 360 degree movement.

It feels to me almost as if it's broken, but it isn't. It's just you can move it around in any direction.

And she uses that finger, initially, to tap on the trunk of the tree and then listening to the echo from that tapping with these huge ears, she can detect where the grubs are. From then, she gnaws through the wood with those rodent like teeth, and then uses this finger again to reach inside the hole and get the bugs out.

So the question is, why?

How could an animal be so precisely adapted to a particular lifestyle?

She's waking up now.

And the answer is natural selection.

See, what must have happened, is way back when the ancestors of the lemurs, the lemuriforms, arrived in Madagascar, there must have been a mutation that lengthened the middle finger ever so slightly of one of those lemurs, and that must have given it an advantage.

That must have allowed it, perhaps, to reach into little holes and search for grubs. There's some reason why that lengthened middle finger meant that that gene was more likely to be passed to the next generation, and then down to the next generation.

So that landscape of possibilities, is narrowed. It's narrowed because that gene persists, and it's persisted now for at least 40 million years because this species has been on one branch of the tree of life now for over 40 million years, and so, over those years that middle finger has got more and more specialised.

Natural selection has allowed the aye-aye's wonderfully mutated finger 'to spread through the population.

And this same law applies to all life.

If you have a mutation that helps you in the struggle to survive, you are more likely to leave more offspring, and in the next generation, that mutation 'is more likely to survive.

So this animal is a beautiful example, probably one of the best in the world, of how the sieve of natural selection produces animals that are perfectly adapted to live in their environment.

Video summary

Professor Brian Cox visits Madagascar to track down the rare aye-aye lemur, and see how it is perfectly adapted to suit its surroundings.

He explains how species of lemurs have evolved to fulfill many different ecological niches on the island.

Brian shows us the unique adaptations of an aye-aye, like its unusual teeth, perfect for gnawing away bark, and its elongated, bony middle finger, which it uses to prize out grubs.

This clip is from the series Wonders of Life.

Teacher Notes

Use the clip as an alternative example of specific adaptations. Students could find out what animals could have competed with the aye-aye on different continents, identifying why they have been successful around the planet.

This clip will be relevant for teaching Biology at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and SQA National 3/4/5 in Scotland.

Bacteria and the development of an oxygen rich atmosphere. video

Professor Brian Cox explains how the Earth developed an oxygen rich atmosphere due to organisms called Cyanobacteria.

Conservation of energy. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the first law of thermodynamics. He describes how energy is always conserved, never created or destroyed.

How has life on Earth become so varied? video

Professor Brian Cox explores how life on Earth is so varied, despite us all being descended from one organism, known as LUCA. He examines how cosmic rays drive the mutations that create evolution.

Jellyfish and photosynthesis. video

Professor Brian Cox sees photosynthesis in action, investigating a unique type of jellyfish that have evolved to carry algae within their bodies and feed off the glucose the plants create.

The arrival of water on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox describes the similarities between isotopes of water on comets and our planet and suggests that the water in the oceans may have come from asteroids.

The origins of life on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox explains that in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, energy is released in the presence of organic molecules.

Evolution of hearing. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the evolution of the mammalian ear bones, the malleus, incus and stapes by using a flicker-book to show how the gill arches of jawless fish altered in size and function.

Evolution of sight. video

Professor Brian Cox shows the stages of the evolution of the eye, from a primitive light sensitive spot, to a complex mammalian eye.

Evolution of the senses. video

Professor Brian Cox compares the way that protists sense and react to their environment with the action potentials found in the nerves of more complex life.

Gravity, size and mass. video

An explanation of how forces including gravity affect organisms. Professor Brian Cox explains that as size doubles, mass increases by a factor of eight.

Size and heat. video

Professor Brian Cox explores the relationship between an organism's body size and its metabolic rate.