Understanding how Earth developed an atmosphere rich in oxygen has taken centuries, and now we know that the secret lies with ancient bacteria.

In 1676, a Dutchman called Anton Leeuwenhoek was trying to find out why pepper is spicy. See, they thought that there were little spikes on peppercorns that dug into your tongue. He was using the microscope, which had been discovered about 50 or 60 years before, but inexplicably had never been used for anything useful before. He put the peppercorns on there and he looked down and he couldn’t see anything. So he thought okay, I’ll grind them up, dissolve them in water and have a look. When he did that, he didn’t see anything interesting in the peppercorns, but he found that there were little animals swimming around. And he said that he estimated he could line about a hundred of the ‘wee little creatures,’ those were his words, up along the length of a single coarse sand grain.

What Leeuwenhoek thought were animals, were in all probability not animals at all. Although he didn’t know it at the time, he’d discovered a whole new domain of life…

Bacteria.

They are by far the most numerous organisms on the Earth. In fact, there are more bacteria on our planet than there are stars in the observable universe. And there is one kind of bacteria more numerous than all the rest.

One of the most striking structures I can see on this slide is a kind of a blue-green filament which is a little colony of a type of bacteria called cyanobacteria… These things are incredibly important organisms.

Fossilised cyanobacteria have been found as far back as 3.5 billion years ago. And at some point, around 2.4 billion years ago, they became the first living things to use pigments to split water apart and use it to make food.

This evolutionary invention was incredibly complex. Even its name is a mouthful. Oxygenic photosynthesis.

It starts with a photon from the Sun hitting that green pigment, chlorophyll. Chlorophyll takes that energy and uses it to boost electrons up a hill, if you like. And when they get to the top, they cascade down a molecular waterfall and the energy is used to make something called ATP, which is essentially the energy currency of life.

This little molecular machine is called Photosystem 2, and it makes energy for the cell, from sunlight. But when the electrons reach the bottom of that waterfall they enter Photosystem 1, they meet some more chlorophyll which is hit by another photon from the Sun, and that energy raises the electrons up again and forces them onto carbon dioxide, turning that carbon dioxide eventually into sugars, into food for the cell. Now, why all this complexity? You know, why do you need these two photosystems joined together in this way just to get some electrons and make sugar and a bit of energy out of it?

It’s because only when life coupled these two biological machines together that it could split water apart and turn it into food. But it wasn’t easy.

The thing is that water is extremely difficult to split. So for a leaf to do it, for a blade of grass to do it, just using a trickle of light from the Sun is extremely difficult.

In fact, the task is so complex that unlike flight or vision, which evolved separately many times during our history, oxygenic photosynthesis has only evolved once. In other words, the descendants of one cyanobacterium that worked out, for some reason, how to couple those complex molecular machines together in some primordial ocean, billions of years ago, are still present on the Earth today.

The cyanobacteria changed the world… Turning it green… And that had a wonderful consequence.

With this new way of living, life released oxygen into the atmosphere of our planet for the first time. And in doing so over hundreds of millions of years it eventually completely transformed the face of our home.

Organisms started using oxygen to respire, yielding a lot more energy which allowed the development of more complex life like plants and animals.

Video summary

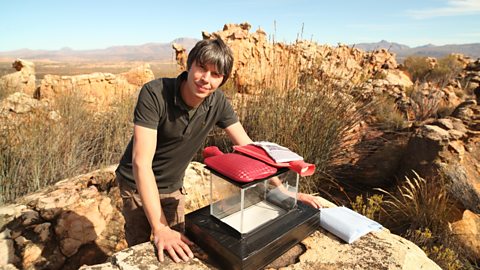

Professor Brian Cox explains how the Earth developed an oxygen rich atmosphere.

The secret lies with an ancient group of organisms called cyanobacteria.

Around 2.4 billion years ago, these bacteria evolved an incredible ability to produce their own food using photosynthetic pigments.

A by-product of this process was oxygen, and the success of these pioneering organisms filled the atmosphere with oxygen.

This transformed our planet and allowed the development of more complex life, like plants and animals.

This clip is from the series Wonders of Life.

Teacher Notes

This clip could be used as a stimulus to discuss how the Earth's early atmosphere changed.

Students could discuss the conditions that must have been present for the bacteria to begin the process of photosynthesis.

This clip will be relevant for teaching Biology at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and SQA National 3/4/5 in Scotland.

Conservation of energy. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the first law of thermodynamics. He describes how energy is always conserved, never created or destroyed.

How has life on Earth become so varied? video

Professor Brian Cox explores how life on Earth is so varied, despite us all being descended from one organism, known as LUCA. He examines how cosmic rays drive the mutations that create evolution.

Lemurs: Evolution and adaptation. video

Professor Brian Cox visits Madagascar to track down the rare aye-aye lemur, and see how it is perfectly adapted to suit its surroundings.

Jellyfish and photosynthesis. video

Professor Brian Cox sees photosynthesis in action, investigating a unique type of jellyfish that have evolved to carry algae within their bodies and feed off the glucose the plants create.

The arrival of water on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox describes the similarities between isotopes of water on comets and our planet and suggests that the water in the oceans may have come from asteroids.

The origins of life on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox explains that in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, energy is released in the presence of organic molecules.

Evolution of hearing. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the evolution of the mammalian ear bones, the malleus, incus and stapes by using a flicker-book to show how the gill arches of jawless fish altered in size and function.

Evolution of sight. video

Professor Brian Cox shows the stages of the evolution of the eye, from a primitive light sensitive spot, to a complex mammalian eye.

Evolution of the senses. video

Professor Brian Cox compares the way that protists sense and react to their environment with the action potentials found in the nerves of more complex life.

Gravity, size and mass. video

An explanation of how forces including gravity affect organisms. Professor Brian Cox explains that as size doubles, mass increases by a factor of eight.

Size and heat. video

Professor Brian Cox explores the relationship between an organism's body size and its metabolic rate.