The needs of animals, and the behaviours they display, is partly dependent on their size. The relationship between volume, and surface area, is especially significant. These are Southern Bent-wing Bats, one of the rarest bat-species in Australia. Every evening, they emerge in their thousands from this cave in order to feed.

When fully grown, these bats are just five and a half centimetres long and weigh around 18 grams. Because of their size, they face a constant struggle to stay alive. Now, we're using a thermal camera here to look at the bats, and you can see that they appear as streaks across the sky, they appear as brightly as me, and that's because they're roughly the same temperature as me. They're known as endotherms. They're animals that maintain their body temperature. And that takes a lot of effort.

These bats have to eat something like three-quarters of their own bodyweight every night, and a lot of that energy goes into maintaining their temperature. As with all living things, the bats eat to provide energy to power their metabolism. Although, like us, they have a high body temperature when they're active, keeping warm is a considerable challenge, on account of their size.

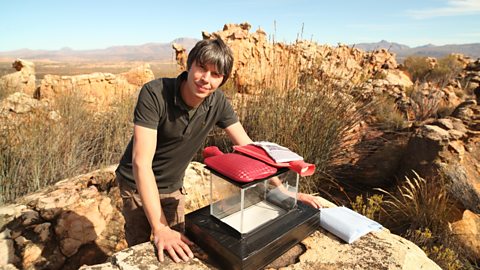

The bats lose heat mostly through the surface of their bodies, but because of simple laws governing the relationship between the surface area of a body and its volume being small creates a problem.' So let's look at our blocks again, but this time for surface area to volume. Here's a big thing.

It's made of eight blocks, so its volume is eight units. And its surface area is two, by two on each side, so that's four, multiplied by the six faces is 24. So the surface area to volume ratio is 24 to eight which is 3 to 1.

Now, look at this smaller thing. This is one block, so it's volume is one unit.

Its surface area is one, by one, by one, six times, so it's six.

So this has a surface area to volume ratio of six to one.

So, as you go from big to small, your surface area to volume ratio increases. Small animals, like bats, have a huge surface area compared to their volume. As a result, they naturally lose heat at a very high rate. To help offset the cost of losing so much energy in the form of heat, the bats are forced to maintain a high rate of metabolism.

They breathe rapidly, their little heart races, and they have to eat a huge amount. So, a bat's size clearly effects the speed at which it lives its life. Right across the natural world, the size you are has a profound effect on your metabolic rate, or your speed of life. Big animals have a much smaller surface area to volume ratio than small animals and that means their rate of heat loss is much smaller.

And that means there's an opportunity there for large animals. They don't have to eat as much food to stay warm, and therefore they can afford a lower metabolic rate.

Now, there's one last consequence of all these scaling laws that I suspect you'll care about more than anything else.

And it's this: there's a strong correlation between the effective cellular metabolic rate of an animal, and its life span.

In other words, as things get bigger, they tend to live longer.

Video summary

Professor Brian Cox explores the relationship between an organism's body size and its metabolic rate.

He explains that smaller animals have a larger surface to volume ratio compared to larger animals. This means they lose heat at a much quicker rate.

To combat this, smaller animals are forced to maintain a high metabolic rate, to keep a constant body temperature; their heart beats at a faster pace and they breathe much quicker, as such smaller animals do not tend to live as long.

This clip is from the series Wonders of Life.

Teacher Notes

This clip could be used to consider how the size of an animal determines its metabolic rate, which in turn determines its life span. This could be determined by providing data on animals so their surface area to volume ratio can be calculated and a correlation either determined or predicted based upon its life span.

This clip will be relevant for teaching Biology at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and SQA National 3/4/5 in Scotland.

Bacteria and the development of an oxygen rich atmosphere. video

Professor Brian Cox explains how the Earth developed an oxygen rich atmosphere due to organisms called Cyanobacteria.

Conservation of energy. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the first law of thermodynamics. He describes how energy is always conserved, never created or destroyed.

How has life on Earth become so varied? video

Professor Brian Cox explores how life on Earth is so varied, despite us all being descended from one organism, known as LUCA. He examines how cosmic rays drive the mutations that create evolution.

Lemurs: Evolution and adaptation. video

Professor Brian Cox visits Madagascar to track down the rare aye-aye lemur, and see how it is perfectly adapted to suit its surroundings.

Jellyfish and photosynthesis. video

Professor Brian Cox sees photosynthesis in action, investigating a unique type of jellyfish that have evolved to carry algae within their bodies and feed off the glucose the plants create.

The arrival of water on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox describes the similarities between isotopes of water on comets and our planet and suggests that the water in the oceans may have come from asteroids.

The origins of life on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox explains that in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, energy is released in the presence of organic molecules.

Evolution of hearing. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the evolution of the mammalian ear bones, the malleus, incus and stapes by using a flicker-book to show how the gill arches of jawless fish altered in size and function.

Evolution of sight. video

Professor Brian Cox shows the stages of the evolution of the eye, from a primitive light sensitive spot, to a complex mammalian eye.

Evolution of the senses. video

Professor Brian Cox compares the way that protists sense and react to their environment with the action potentials found in the nerves of more complex life.

Gravity, size and mass. video

An explanation of how forces including gravity affect organisms. Professor Brian Cox explains that as size doubles, mass increases by a factor of eight.