Energy is a concept that’s central to physics, but because it’s a word we use every day its meaning has got a bit woolly. I mean, it’s easy to say what it is in a sense. Obviously this river has got energy because over the decades and centuries it’s cut this valley through solid rock.

But while this description sounds simple, in reality things are a little more complicated.

Over the years, the nature of energy has proved notoriously difficult to pin down. Not least because it has the seemingly magical property that it never runs out. It only ever changes from one form to another.

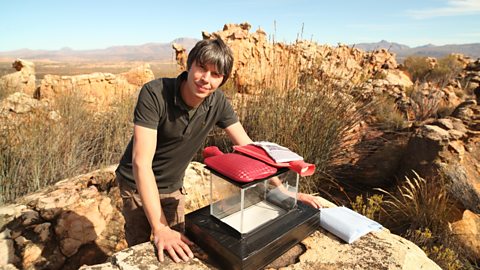

Take the water in that waterfall. at the top of the waterfall it’s got something called gravitational potential energy, which is the energy it possesses due to its height above the Earth’s surface. See, if I scoop some water out of the river into this beaker, then I’d have to do work to carry it up to the top of the waterfall. I’d have to expend energy to get it up there. So it would have that energy as gravitational potential.

I can even do the sums for you. Half a litre of water has a mass of half a kilogram. Multiply by the height, that’s about five metres, and the acceleration due to gravity is about ten metres per second squared. So that’s half times five times ten is 25 joules. So I’d have to put in 25 joules to carry this water to the top of the waterfall. Then if I emptied it over the top of the waterfall, then all that gravitational potential energy would be transformed into other types of energy.

Sound, which is pressure waves in the air. There’s the energy of the waves in the river. And there’s heat. So it’ll be a bit hotter down there because the water’s cascading into the pool at the bottom of the waterfall. Buy the key thing is energy is conserved, it’s not created or destroyed.

So because energy is conserved, if I were to add up all the energy in the water waves, all the energy in the sound waves, all the heat energy at the bottom of the pool, then I would find that it would be precisely equal to the gravitational potential energy at the top of the falls.

What’s true for the waterfall is true for everything in the universe. It’s a fundamental law of nature, known as the First Law of Thermodynamics. And the fact that energy is neither created nor destroyed has a profound implication. It means energy is eternal.

Every single joule of energy in the universe today was present at the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago.

Potential energy held in primordial clouds of gas and dust was transformed into kinetic energy as they collapsed to form stars and planetary systems just like our own solar system.

Video summary

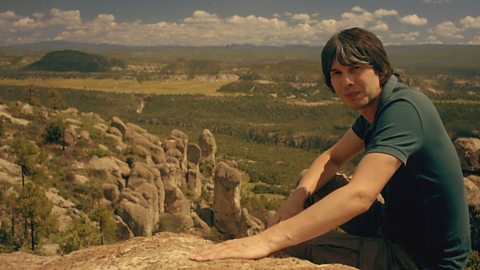

Professor Brian Cox explains the first law of thermodynamics.

He describes how energy is always conserved, never created or destroyed.

He uses an analogy of a waterfall to explain how gravitational potential energy (for which he gives the formula) is converted into other forms.

He ends with the quote, “Every single joule of energy in the universe today was present at the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago.”

This clip is from the series Wonders of Life.

Teacher Notes

Students could review the different types of energy and the conversions that occur between them. Can they identify the conversions involved in a hairdryer or toaster? The relationship between energy and work can then be covered.

Students can be asked why the units of both are joules. Rollercoaster rides are likely to be a useful example of how gravitational potential energy is converted to kinetic energy.

Can students explain the similarities and differences between a waterfall and a rollercoaster?

This clip will be relevant for teaching Physics. This topic appears in OCR, Edexcel, AQA, WJEC KS3 and GCSE in England and Wales, CCEA GCSE in Northern Ireland and SQA National 4 and 5 and Higher in Scotland.

Bacteria and the development of an oxygen rich atmosphere. video

Professor Brian Cox explains how the Earth developed an oxygen rich atmosphere due to organisms called Cyanobacteria.

How has life on Earth become so varied? video

Professor Brian Cox explores how life on Earth is so varied, despite us all being descended from one organism, known as LUCA. He examines how cosmic rays drive the mutations that create evolution.

Lemurs: Evolution and adaptation. video

Professor Brian Cox visits Madagascar to track down the rare aye-aye lemur, and see how it is perfectly adapted to suit its surroundings.

Jellyfish and photosynthesis. video

Professor Brian Cox sees photosynthesis in action, investigating a unique type of jellyfish that have evolved to carry algae within their bodies and feed off the glucose the plants create.

The arrival of water on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox describes the similarities between isotopes of water on comets and our planet and suggests that the water in the oceans may have come from asteroids.

The origins of life on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox explains that in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, energy is released in the presence of organic molecules.

Evolution of hearing. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the evolution of the mammalian ear bones, the malleus, incus and stapes by using a flicker-book to show how the gill arches of jawless fish altered in size and function.

Evolution of sight. video

Professor Brian Cox shows the stages of the evolution of the eye, from a primitive light sensitive spot, to a complex mammalian eye.

Evolution of the senses. video

Professor Brian Cox compares the way that protists sense and react to their environment with the action potentials found in the nerves of more complex life.

Gravity, size and mass. video

An explanation of how forces including gravity affect organisms. Professor Brian Cox explains that as size doubles, mass increases by a factor of eight.

Size and heat. video

Professor Brian Cox explores the relationship between an organism's body size and its metabolic rate.