Evolution in plants and animals is closely linked to changing environments. However, life is not only shaped by its surroundings. There are limitations to form and function, imposed by the fundamental forces of nature. And you can clearly see them at work, when you examine the size of life.

Our world is covered in giants. The largest things that ever lived on this planet weren't the dinosaurs, they're not even blue whales. They're trees. These are mountain ash. They're the largest flowering plant in the world.

They grow about a metre a year, and these trees are 60, 70, even 80 metres high. To get this big, you need to face some very significant physical challenges. These giants can live to well over 300 years old. But they don't keep growing forever. There are limits to how big each tree can get. As with all living things the structure, form, and function of these trees' has been shaped by the process of evolution through natural selection. But evolution doesn't have a free hand.

It is constrained by the universal laws of physics.

Each tree has to support its mass against the downwards force of Earth's gravity. At the same time, the trees rely on the strength of the interactions between molecules to raise a column of water from the ground, up to the leaves in the canopy. And it's these fundamental properties of nature that act together to limit the maximum height of a tree. Which, theoretically, lies somewhere in the region of 130 metres. Gravity doesn't just influence how tall a plant can grow.

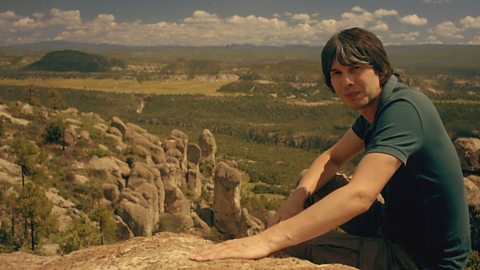

It also effects how big animals can get. To show you how, I've come to track down one of Australia's most iconic animals. The red kangaroo.

Red Kangaroos are Australia's largest native land mammal. The evolution of the ability to hop gives kangaroos a cheap and efficient way to get around. But not everything can move like a kangaroo.

The red kangaroo is the largest animal in the world that moves in this unique way. Hopping across the landscape at high speed. And there are reasons why there aren't giant hopping elephants, or dinosaurs, and they're not really biological. It's not down to the details of evolution by natural selection or environmental pressures.

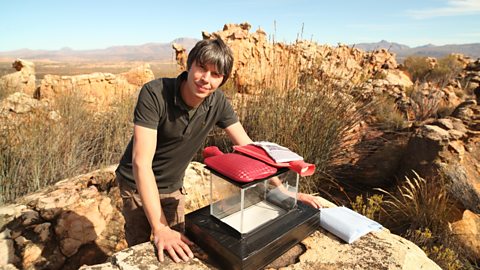

The larger an animal gets, the more severe the restrictions on its body shape and its movement. And it's gravity that imposes these restrictions. To understand why this is the case, I want to explore what happens to the mass of a body when that body increases in size. Take a look at this block. Let's say it has width one, length one, and height one. And its volume is one, multiplied by one, multiplied by one, which is one cubic things, whatever the measurement is.

Now, it's mass is proportional to the volume, so we could say that the mass of this block is one unit as well. Let's say that we're gonna double the size of this thing. In the sense that we want to double its width, double its length, double its height.

Then its volume is two, multiplied by two, multiplied by two, equals eight cubic things. Its volume has increased by a factor of eight. And so, its mass has increased by a factor of eight as well. So, although I've only doubled the size of the blocks, I've increased the total mass by eight. As things get bigger, the mass of a body goes up by the cube of the increase in size. Because of this scaling relationship, The larger you get, the greater the effect of gravity.

As things get bigger, the huge increase in mass has a significant impact on the way large animals support themselves against gravity, and how they move about. No matter how energy efficient and advantageous it is to hop like a kangaroo, as you get bigger, it's just not physically possible.

So gravity limits how big life can get, but it's not the physical force that controls how small an animal can get. And in fact, the smaller you are, the less gravity effects your life. This is the rhinoceros beetle, named for obvious reasons. But actually it's just the males who have the distinctive horns on their heads.

Gram for gram, these insects are among the strongest animals alive. I can demonstrate that by just getting hold the top of his head. Doesn't hurt him at all. But watch… What he is able… To do. Look at that.

So, he's hanging onto this branch, which is many times his own body weight. Absolutely no distress at all. As things get smaller, it's a rule of nature that they inevitably get stronger. The reason is quite simple. Small things have relatively large muscles, compared to their tiny body mass. And this makes them very powerful.

The beetles also appear to have a cavalier attitude to the effects of gravity. If they should fall, they just bounce, and walk off. If I fell a similar distance relative to my size, I'd break.

So why does size much such a difference?

Time for a bit of fundamental physics. All things fall at the same rate under gravity.

That's because they're following geodesics through curved space-time, but that's not important. The important thing for biology, is that although everything falls at the same rate, it doesn't meet the same fate when it hits the ground. The grape bounces. A melon… doesn't bounce.

Now the reasons for that are quite complex, actually. First of all, the grape has a larger surface area, in relation to its volume, and therefore its mass than the melon. And so, although in a vacuum if you took away the air, they would both fall at the same rate, actually, in reality, the grape falls a bit slower than the melon. Also, the melon is more massive, and so it has more kinetic energy when it hits the ground. Remember from physics class? Kinetic energy is a half mv squared.

So if you reduce m, you reduce the energy. The upshot of that, is that the melon has a lot more energy when it hits the ground. It has to dissipate it in some way, and it dissipates it by exploding.

So gravity is a force that governs the form and function of larger plants and animals. It sets a limit to just how big they can get. And exerts a greater influence over the lives of the very large.

Video summary

An organism’s structure, form and function are shaped by the process of evolution.

However, as Professor Cox explains, evolution is constrained by the universal forces of physics, like gravity.

He explains why gravity limits the size of plants and animals.

Using blocks of wood, he demonstrates how a doubling of linear size results in an eight-fold increase in mass.

He describes the limitations this relationship has on animals including the kangaroo and rhinoceros beetle.

This clip is from the series Wonders of Life.

Teacher Notes

Students can use an experiment to assess the effects of gravity.

Equipment needed is: a plastic cup, water, an outside area, a beaker or bucket.

Push a hole into the side of the cup. Cover with your thumb and fill with water.

Hold the cup up high and remove your thumb. The water will gush out easily.

Pose the question 'What would happen if you then dropped the cup?'

Repeat the experiment but drop it this time. You should observe the water not flowing out of the hole but remaining in the cup until it hits the floor. Gravity pulls down on the cup and water equally and does not push it through the hole.

This clip will be relevant for teaching Physics and Biology. This topic appears in OCR, Edexcel, AQA, WJEC KS3, KS4 and GCSE in England and Wales, CCEA GCSE in Northern Ireland and SQA National 4/5 in Scotland.

Bacteria and the development of an oxygen rich atmosphere. video

Professor Brian Cox explains how the Earth developed an oxygen rich atmosphere due to organisms called Cyanobacteria.

Conservation of energy. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the first law of thermodynamics. He describes how energy is always conserved, never created or destroyed.

How has life on Earth become so varied? video

Professor Brian Cox explores how life on Earth is so varied, despite us all being descended from one organism, known as LUCA. He examines how cosmic rays drive the mutations that create evolution.

Lemurs: Evolution and adaptation. video

Professor Brian Cox visits Madagascar to track down the rare aye-aye lemur, and see how it is perfectly adapted to suit its surroundings.

Jellyfish and photosynthesis. video

Professor Brian Cox sees photosynthesis in action, investigating a unique type of jellyfish that have evolved to carry algae within their bodies and feed off the glucose the plants create.

The arrival of water on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox describes the similarities between isotopes of water on comets and our planet and suggests that the water in the oceans may have come from asteroids.

The origins of life on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox explains that in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, energy is released in the presence of organic molecules.

Evolution of hearing. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the evolution of the mammalian ear bones, the malleus, incus and stapes by using a flicker-book to show how the gill arches of jawless fish altered in size and function.

Evolution of sight. video

Professor Brian Cox shows the stages of the evolution of the eye, from a primitive light sensitive spot, to a complex mammalian eye.

Evolution of the senses. video

Professor Brian Cox compares the way that protists sense and react to their environment with the action potentials found in the nerves of more complex life.

Size and heat. video

Professor Brian Cox explores the relationship between an organism's body size and its metabolic rate.