No cry or happy sound: Di hospital ward full of pikin wey dey starve

Wia dis foto come from, BBC/Imogen Anderson

- Author, Yogita Limaye

- Role, BBC News, Jalalabad

- Read am in 8 mins

Warning: Dis tori get some kain details wey fit worry you from di beginning.

“Dis be like doomsday for me. I feel so much grief. Can you imagine wetin I don go through as I dey watch my children dey die?” Amina tok.

She don lose six children. None of dem live pass di age of three and anoda one dey battle for her life now.

Seven-month-old Bibi Hajira stll dey di size of new born pikin. Suffering from severe acute malnutrition.

She occupy half of one bed for one ward for Jalalabad regional hospital for Afghanistan eastern Nangarhar province.

“My pikin dem dey die sake of poverty. All I fit feed dem na dry bread, and water wey I warm up by keeping am under sun,” Amina tok, as nearly shout in sorrow.

Wetin dey pain pass be say her tori no dey unique at all – and say dem fit to save so many more lives wit timely treatment.

Wia dis foto come from, BBC/Imogen Anderson

Bibi Hajira na one among di 3.2 million children wey dey suffer acute malnutrition, wey dey destroy di kontri.

Dis na condition wey don dey worry Afghanistan for decades, sake of 40 years of war, extreme poverty plus plenty oda issues inside three years since Taliban take over.

But di situation don enta anoda level like neva bifor.

E dey hard for anyone to imagine wetin 3.2 million look like, and so di tori from just one small hospital room fit torchlight small on dis disaster as e dey happun.

Na 18 toddlers dey on seven beds. Dis no be seasonal crowd, dis na how e dey happun normally.

No cry or happy sound. Na only di noise of one pulse rate monitor dey break di worrying silence.

Most of di children no take sleep medicine or wear oxygen masks. Dem dey awake but dem just dey too weak to move or make any sound.

Sharing di bed wit Bibi Hajira, wearing one purple cloth, her tiny arm cover her face, na three-year-old Sana.

Her mama die as she dey born her baby sister few months ago, so her aunt Laila na she dey take care of her.

Laila touch my arm and hold up seven fingers – one for each child wey she lost.

For anoda bed na dia three-year-old Ilham le. Ilham dey far too small for im age, skin dey peeling off im arms, legs and face. Three years ago, im sister die wen she bin dey two years.

E dey too painful to even look at one-year-old Asma.

She get beautiful hazel eyes and long eyelashes, but dem dey wide open, dem no dey blink as she dey breath heavily into oxygen mask wey cover most of her little face.

Wia dis foto come from, BBC/Imogen Anderson

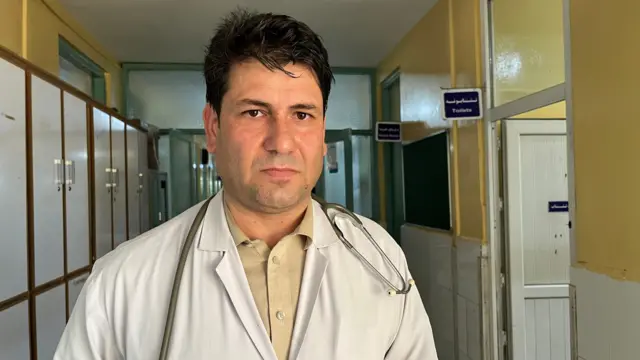

Dr Sikandar Ghani, wey dey stand ova her, shake im head. “I no tink say she go survive,” im say. Asma tiny body don go into septic shock.

Despite di circumstances, up until dat time evri body for di room just dey endure – nurses and mothers just dey do dia work dey go, feeding di children, petting dem. Evri tin stop, broken look on so many faces.

Asma mama, Nasiba dey cry. She lift her veil and lean down to kiss her daughter.

“E feel like say di flesh dey melt from my body. I no fit bear to see her suffering like dis,” she cry.

Nasiba don also already lost three children. “My husband na labourer. Wen im get work, we go chop.”

Dr Ghani tell us say, Asma fit suffer heart attack any moment. We leave di room. Less dan one hour later, she die.

Seven hundred children don die inside di past six months for di hospital – more dan three a day, di Taliban public health department for Nangarhar tell us.

Di number plenty no be small, but dem for get even more deaths if to say World Bank and Unicef funding bin no dey to run di facility.

Up until August 2021, international funds wey dem bin dey give directly to di former goment na im dem bin take dey run nearly all public healthcare for Afghanistan.

Wen Taliban take over, di money stop becos of international sanctions against dem.

Dis one make di to healthcare collapse. Aid agencies step in to provide wetin suppose be temporary emergency response.

Wia dis foto come from, BBC/Imogen Anderson

From start, dis one bin be unsustainable solution, and now, for world wey dey distracted by so many oda, funding for Afghanistan don shrink.

Equally, Taliban goment policies, specifically dia restrictions on women, don mean say donors dey get two minds to give funds.

“We inherit di problem of poverty and malnutrition, wey don become worse sake of natural disasters like floods and climate change. Di international community gatz increase humanitarian aid, dem no suppose connect am wit political and internal issues,” Hamdullah Fitrat, di Taliban goment deputy tok tok pesin, tell us.

Since di past three years we don go to more dan twelve health facilities for di kontri, and take our eyes see as di situation dey get worse rapidly.

During each of our past few visit to hospitals, we don witness children dey die.

But wetin we don also see na evidence say di correct treatment fit save children.

Bibi Hajira, wey bin dey fragile condition wen we visit di hospital, dey much beta now and dem don discharge am, Dr Ghani tell us for phone.

“If we bin get more medicines, facilities and staff we fit save more children. Our staff get strong commitment. We dey work tirelessly and ready to do more,” im tok.

“I also get children. When pikin die, we all dey also suffer. I know wetin must go through di hearts of di parents.”

Wia dis foto come from, BBC/Imogen Anderson

Malnutrition no be di only cause of increase in mortality. Oda preventable and curable diseases dey also kill children.

For di intensive care unit next door to di malnutrition ward, six-month-old Umrah dey battle serious pneumonia.

She dey cry loudly as one nurse dey attach saline drip to her body. Umrah mama Nasreen sidon by her, tears dey fall down her face.

“I wish I fit die in her place. I dey fear well-well,” she tok. Two days afta we visit di hospital, Umrah die.

Dis na di tori dem of di ones wey bin fit reach hospital. Countless odas bin no fit.

Only one out of five children wey need hospital treatment fit get am for Jalalabad hospital.

Di pressure on di facility dey so serious sotey, almost immediately afta Asma die, dem move one tiny baby, three-month-old Aaliya, to di half of bed wey Asma vacate.

No one for di room get time to process wetin bin happun. Anoda seriously sick pikin dey wait for treatment.

Jalalabad hospital dey take care of di population of five provinces, wey according to di Taliban goment get population of about five million pipo.

And now di pressure on am don increase more. Most of more dan 700,000 Afghan refugees wey Pakistan bin deport by force since late last year kontinu to stay for Nangarhar.

For di communities around di hospital, we find evidence of anoda alarming statistic wey UN release dis year: say 45% of children under di age of five no dey grow – dem dey shorter dan dem suppose dey - for Afghanistan.

Robina her two-year-old son Mohammed no still fit stand and im dey more shorter dan im suppose.

Wia dis foto come from, BBC/Imogen Anderson

“Di doctor tell me say if im get treatment for di next three to six months, im go dey fine. But we no even fit even afford food. How we wan pay for di treatment?” Robina ask.

She and her family leave Pakistan last year and now dem dey live for one dusty, dry settlement for di Sheikh Misri area, wey be short drive on mud road from Jalalabad.

“I dey fear say im go dey disabled and im no go ever fit waka," Robina say.

“For Pakistan, we also bin face hard life. But work bin dey. Here my husband, wey be labourer, dey rarely find work. We for treat am if to say we still dey Pakistan.”

Wia dis foto come from, BBC/Imogen Anderson

Unicef say stunting fit cause serious physical and mental damage wey fit become permanent, di effect fit last throughout di pesin life plus even affect im next generation.

“Afghanistan dey already struggle economically. If large sections of our future generation dey physically or mentally disabled, how our society wan take help dem?” Dr Ghani ask.

Mohammad still fit dey saved from permanent damage if im get treatment bifor e too late.

But di community nutrition programmes wey aid agencies dey run for Afghanistan don see di most dramatic reduction – many of dem bin receive just one quarter of di funding wey dem need.

Wia dis foto come from, BBC/Imogen Anderson

Lane afta lane for Sheikh Misri we meet families wit malnourished or stunted children.

Sardar Gul get two malnourished children – three-year-old Umar and eight-month-old Mujib, one small boy wit bright eyes wey im carry for im lap.

“A month ago Mujib weight bin drop to less dan three kilos. Once we bin dey able to register am wit one aid agency, we begin get food sachets. Dem don really help am,” Sardar Gul tok.

Now, Mujib dey weigh six kilos - still some kilos underweight, but im don significantly improve.

Dis na evidence say timely intervention fit help save children from death and disability.

Additional reporting: Imogen Anderson and Sanjay Ganguly