EDWARD JENNER:I'm going to tell you something about my life.

EDWARD JENNER:My name is Edward Jenner.

EDWARD JENNER:I was born in 1749, in a small town in the countryside.

EDWARD JENNER:When I grew up, I became a doctor.

EDWARD JENNER:But to understand why, I must start my story long before then, back to when I was just eight years of age.

EDWARD JENNER:That's the year something terrible happened in our town.

EDWARD JENNER:Something terrible happened to me.

EDWARD JENNER:'That summer, there was an outbreak of smallpox.

EDWARD JENNER:'You might not have heard of it, but smallpox was a terrible disease.

EDWARD JENNER:'It was very infectious, which meant it was easily passedfrom one person to another.

EDWARD JENNER:'We were told to keep well away from anyone who had it.

EDWARD JENNER:'But I couldn't keep away, I couldn't resist. I just had to see for myself what a person with smallpox looked like.

EDWARD JENNER:'It was a terrible sight.

EDWARD JENNER:'The worst thing I'd seen.

EDWARD JENNER:'I ran.

EDWARD JENNER:'I didn't want to end up covered in nasty scabs and most probably dead.

EDWARD JENNER:'Dead was definitely not something I wanted to be.

EDWARD JENNER:'There was no cure for it.

EDWARD JENNER:'You could call for the doctor, but there would be nothing he could do.

EDWARD JENNER:'Once you got it, that was that.'

EDWARD JENNER:Well, people were desperate. So they tried different things.

EDWARD JENNER:One of the things they tried was to actually give you smallpox.

EDWARD JENNER:They thought if they could give you just a little bit, you might not get it too bad, and if you did recover from it, then you'd never catch it again.

EDWARD JENNER:So I was just eight years old when I was told I was going to be given smallpox deliberately.

EDWARD JENNER:Well,

EDWARD JENNER:I'd never been so scared.

EDWARD JENNER:Not in all my life.

EDWARD JENNER:'The worst part was, well, not the worst part, but the first worst part, was that they starved us first.

EDWARD JENNER:'For three weeks, we had very little food.

EDWARD JENNER:'I was so hungry, and I was scared too.

EDWARD JENNER:'I didn't want smallpox. What I wanted was a big pie and some apple cake.

EDWARD JENNER:'Then we were sent to see the doctor in the stables.

EDWARD JENNER:'I wanted to run away, but I didn't.

EDWARD JENNER:'I had to see for myself what he would do to us. I'd never been so scared. Not in all my life.

EDWARD JENNER:'But the waiting wasn't the worst of it.

EDWARD JENNER:'What was worse was that the doctor was grinding up something horrid.

EDWARD JENNER:'The stuff he was grinding up was scabs. Scabs like I'd seen on the boy with smallpox.

EDWARD JENNER:'But the grinding wasn't the worst of it.

EDWARD JENNER:'One at a time we went in, then the doctor blew the powdered scabs right up our noses.

EDWARD JENNER:'Imagine that! Someone else's scabs going right up your nose.

EDWARD JENNER:'It felt like the worst moment of my life.

EDWARD JENNER:'But that wasn't the worst of it. The worst of it was that we couldn't leave the stables.

COUGHING

EDWARD JENNER:'We had to lie there in the straw, with the smell of the horses, and wait for the smallpox to take hold.

EDWARD JENNER:'And when it did, I couldn't have moved if I wanted to. My body felt like it was made of lead.

EDWARD JENNER:'Weeks, it was. I lost track of when it was day and when it was night.

EDWARD JENNER:'Eventually I started to feel better.

EDWARD JENNER:'But one boy, he had got the smallpox badly and he died in the night.

EDWARD JENNER:'I swore then that there had to be a better way.

EDWARD JENNER:'And I knew, in that moment, I would become a doctor.

EDWARD JENNER:'When I grew up, that's exactly what I did.'

EDWARD JENNER:I became a family doctor.

EDWARD JENNER:But I often thought of that lad I spied on through the window.

EDWARD JENNER:And the poor young boy who died next to me in the stables.

EDWARD JENNER:I made a decision. I would try to find a way to beat smallpox.

EDWARD JENNER:'I read everything I could find about the disease.

EDWARD JENNER:'I spent weeks in my room, scrutinising scabs, and I really couldn't think of anything but smallpox.

EDWARD JENNER:'Then one day a woman came to see me. Said her name was Sarah, and that she was a milkmaid whose job it was to milk the farmer's cows. She showed me a sore on her hand.

EDWARD JENNER:'I knew at once it was a harmless disease called cowpox. Something milkmaids often caught from cows they spent their days milking.

EDWARD JENNER:'Then she said it was good she got cowpox, because that meant she couldn't get smallpox.

EDWARD JENNER:'This idea that cowpox could stop you getting smallpox made me think. What if there was some truth in it?

EDWARD JENNER:'What I needed was to meet more milkmaids. I needed to see for myself if it could be true.

COCKEREL CROWS

EDWARD JENNER:'Now, I confess, I did like milkmaids. They always had such lovely skin.

EDWARD JENNER:'It turned out they all said exactly the same thing.

EDWARD JENNER:'That they didn't get smallpox, and had such lovely skin, because they caught cowpox from the cows instead.

EDWARD JENNER:'Well I was excited.

EDWARD JENNER:'I knew what to do next. I would experiment. I would test the idea that cowpox could stop you getting smallpox.

MOO

EDWARD JENNER:'The son of my gardener was a small boy called James.

EDWARD JENNER:'He was brave enough to let me try my theory out on him.

EDWARD JENNER:'I took some of the pus from Sarah's cowpox sore.

EDWARD JENNER:'I made a tiny cut on James' arm.

EDWARD JENNER:'I put the cowpox pus in it. Doing this meant I was giving him cowpox.

EDWARD JENNER:'After a few weeks had passed, I gave him a small amount of smallpox in the same way.

EDWARD JENNER:'If the milkmaids were right, the boy, like them, wouldn't get smallpox, because the cowpox would stop him from getting it.

EDWARD JENNER:'Get it wrong, and the poor lad might get very sick indeed.

EDWARD JENNER:'I watched him like a hawk. I looked him over, checked him out. I followed him around.

EDWARD JENNER:'I waited for signs of smallpox, but nothing happened.

EDWARD JENNER:'I watched and waited, but still nothing happened.

EDWARD JENNER:'To my sheer delight, he was completely fine.

EDWARD JENNER:'I knew then that it was true! That it must have been the cowpox that stopped him getting smallpox.' It was the most extraordinarily simple thing.

EDWARD JENNER:I did a few more experiments to be doubly sure it worked. I called it a vaccine, after the Latin word for cow.

EDWARD JENNER:Once smallpox was a killer disease. Now there's no smallpox anywhere in the world.

EDWARD JENNER:They say my vaccine saved more lives than the work of any other man.

EDWARD JENNER:So it goes to show, sometimes the worst things can lead to the best things.

EDWARD JENNER:The weeks I spent in those stables spurred me on to find a cure for smallpox.

EDWARD JENNER:So I guess you could say it's thanks to me you will never get it.

Video summary

This short film is for teacher use and contains some scenes that pupils might find upsetting. Teacher review is recommended prior to use in class.

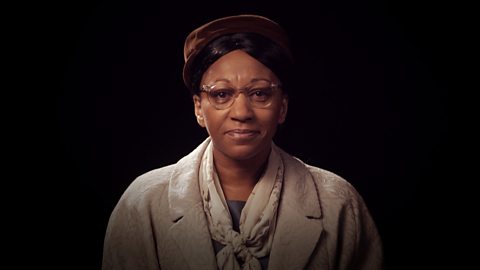

Edward Jenner tells the story of his life and how he discovered how to vaccinate people against smallpox.

Told in the first person, and brought to life with a mix of drama, movement, music and animation, the story begins when Jenner was a boy.

There was an outbreak of smallpox in the town where he lived.

He was curious, and had to see for himself what someone with smallpox looked like - it was a frightening sight.

More frightening still, however, was that the only known cure was to infect a person with smallpox before they caught it, in the hope that they would recover and not catch it again.

So at the age of eight Jenner was given smallpox, deliberately.

The experience had a huge impact on him and he vowed to find a way to beat the disease.

He went on to develop a vaccine for smallpox, which would ultimately save millions of lives.

This short film was originally broadcast in 2012 as part of BBC Two's 'Learning Zone'. Teacher review is recommended prior to use in class.

Teacher Notes

Questions to consider whilst watching the film

Depending on the focus of your lesson, you may wish to ask the following questions after the video or pause the short film at certain points to check for understanding.

- Why was smallpox a terrible disease?

- Why was Edward Jenner deliberately given smallpox at the age of eight?

- What did Jenner do when he became an adult?

- Why was his meeting with Sarah, the milkmaid, so important?

- What did Jenner do to his gardener’s son, James?

- Why did he call his discovery a vaccine?

Learning activities to explore after the video

History is a subject which can lend itself to a wide range of cross-curricular links. As a teacher, you will have a greater awareness of how this topic may act as stimulus for learning in other subjects. However, the suggestions below relate solely to ways of developing the children’s historical knowledge and understanding.

Key Question: How was Edward Jenner’s discovery a turning point in the history of medicine?

Overview and DepthThere are two approaches to the study of history:

Overview - An overview study is when pupils study the broad sweep of history, exploring a long period of time, with the aim of identifying key turning points. A depth study requires pupils to study a place, an event or individual in detail. Each of these approaches could be adopted when following up on this film of Edward Jenner.

Depth - Another approach is a depth study of Edward Jenner. Alongside the video, which would be the main source, there are other web-based sources which could be studied in the classroom. Firstly, the Science Museum Group has a 3D model of Edward Jenner’s medicine chest and the website also has guidance about using this and other 3D models in the classroom.

The National Archives website has an engraving of the St Pancras Smallpox and Inoculation Hospital, which would prove to be an engaging stimulus in the classroom. The rest of this webpage, designed for GCSE students, explores the issue of compulsory vaccination, a topic that primary pupils could certainly discuss, though the written sources are not as accessible to KS2 pupils.

These three sources could provide the evidence for written work, highlighting how his vaccination was a key turning point in history. There are a number of genres in which the writing could be captured. One could be a formal entry for an encyclopaedia or a newspaper obituary. A creative alternative would be for the pupils to design a memorial statue for Jenner and decide what should be the inscription on a plinth.

OverviewAnother approach is to place the work of Edward Jenner within its historical context so that pupils can understand he was not the only pioneer at this time and that there were a number of key turning points.

There are two BBC Teach videos in the series Medicine Through Time, which look at the changes in medicine during the 18th and 19th century and these would be appropriate for providing content. In the first, there is some overlap with the Jenner video but whereas it stops with the success of the vaccination, this other video explores the reaction from the church and the scientific community at the time as well as looking at other figures such as John Hunter. However, it was the 19th century which saw the greatest progress in medicine and a number of key figures are explored in this video. Although both these films are aimed at secondary pupils, they are accessible to upper KS2.

The concept of change and continuity

An overview of medicine and health over a period of around 1000 years is a common topic studied at GCSE where students are encouraged to explain the importance of a number of factors in encouraging or inhibiting change. At KS2, the children would not be exploring all of these factors (or covering all the content) but when looking at these videos, the pupils could assess the importance one or more of these factors:

- superstition and religion.

- chance.

- science and technology.

- the role of the individual.

Learning aims or objectives

England

From the History national curriculum

Pupils should:

- understand historical concepts such as continuity and change.

- understand the methods of historical enquiry, including how evidence is used rigorously to make historical claims.

Northern Ireland

From the statutory requirements for Key Stage 2: The World Around Us

Pupils should be enabled to explore:

- Change over time in places.

Teaching should provide opportunities for children as they move through Key Stages 1 and 2 to progress:

- from identifying similarities and differences to investigating similarities and differences, patterns and change.

Scotland

From the Experiences and Outcomes for planning learning, teaching and assessment of

Second Level Social Studies:

- I can use primary and secondary sources selectively to research events in the past.

Wales

From the new Humanities Area of Learning and Experience

School curriculum design for history should:

- develop rich content across the time periods, through which learners can develop an understanding of chronology through exploring … change and continuity…the use of evidence.

Principles of progression

Descriptions of learning for Progression Step 2

Human societies are complex and diverse, and shaped by human actions and beliefs:

- I can identify aspects of life in my community that have changed over time.

Elizabeth Fry. video

Elizabeth Fry describes how she reformed life for prisoners and their families in prison.

Grace Darling. video

Grace Darling describes the night she and her father rowed out in a boat to save sailors.

Rosa Parks. video

How Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat changed the rules of American society.

Thomas Barnardo. video

Thomas Barnardo tells the story of setting up his first home for London's street children.

Alexander Graham Bell. video

Alexander Graham Bell tells the story of his life and describes how he invented the telephone.

Florence Nightingale. video

Florence Nightingale tells the story of her life and how she grew up to become a nurse.

Harriet Tubman. video

Harriet Tubman explains how she escaped slavery and then helped others to do so.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel. video

Isambard Kingdom Brunel shares how he became an engineer and tunnelled through Box Hill.

Mary Anning. video

Mary Anning describes how her astonishing fossil finds changed scientific thinking.