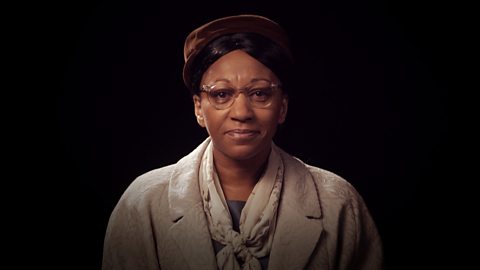

Thomas Barnardo:

I’m going to tell you something about my life.

My name is Thomas Barnardo.

I was born in 1845 in Dublin in Ireland .

I should start my story when I was a boy.

That way you’ll understand the things that happened in my life that changed the way I saw the world and my place in it.

VO:When I was a boy I was grumpy and selfish and thought only of myself.

If someone else had something, I felt it really should be mine.

I was short, and ordinary.

I got angry at people for no reason, and when they didn’t get angry back it made me so confused!

VO:

Then something changed, although it’s hard to say exactly what happened, to make me see the world differently.

For starters, I grew up.

I went from the boy who could think only of what he could do for himself, and became a man obsessed with how I could best do things for others.

It was as if I needed to make up for all the things I had taken.That’s why I decided to go to London to train to be a doctor.

My plan was to go to China once I’d qualified to help poor people there, but I soon realised there were plenty of poor people right under my nose in London, in desperate need of help.

VO:

The East End of London was one of the poorest places a person could find themselves.

A slum it was, cramped and dirty and stinking and just plain awful.

Not fit for a dog.

VO:But there were thousands of people who had no choice but to call it ‘home’.

They lived all crammed in together, sometimes dozens to a single room.

It was a maze of filthy streets, a place where disease and criminals ran riot, and a place that could drive a person to despair.

Baby crying

VO:

I wanted to help, but at first I didn’t know how.

I walked the slums and tried to read the bible to people to give them hope.

But it wasn’t enough.Baby crying

I knew that because school was something you had to pay for, the children who lived in the slums had no chance of an education.

VO:

So I decided to set up a school.

It was called the Ragged School. We would offer free learning to any child that wanted to attend.

They were indeed a ‘ragged’ lot.

They’d never been to school before, or sat at a desk.

They couldn’t concentrate, and they couldn’t sit still.

VO:

But I was patient with them, and eventually I managed to bring them round, til they listened to every word I said!

I felt a real satisfaction then, watching them all write out their letters on a board.

A little reading and writing might give them a chance at least to find work.Bell ringing

VO:

Then one day something happened to make me realise how little I had really done.

It was the end of an ordinary day and the children had left and all gone home.

VO:

I was going upstairs to lock the doors, thinking the place was empty, when I came across a small boy called Jim Jarvis.

I told him it was time to go home, and he asked if he could stay where he was til next morning.

I said I had to lock up, that he should go home to his mother.

He told me then that he had no mother nor any father neither.

He told me then that he had no home to go to.

It was a shock to me, that a boy as small as he could have no home at all, and no mother to kiss his head and give him supper.

VO:

I asked him if there were other boys the same, and if he could show me where they slept.

He took me deep into the slums, and we climbed up to the roof of some building.

And sure enough, there, on a rooftop, huddled together like baby mice, were a group of boys some of them even smaller than small Jim Jarvis.

It was a sight that would stay with me, a sight that would spur me on.

I couldn’t shake the thought that there were children with no home to go to, littering the rooftops on cold London nights.

I had to do something, and as soon as I could raise the funds I opened a home for homeless boys.

We had space for 25 boys, and in no time at all we were full up.

We gave those boys a home, a hearty breakfast and a warm bed at night. And we gave them skills that could lead them to a better life.

VO:

One night there was a knock at the door.

A boy stood there looking cold and hungry.

He asked to be let in, saying he had nowhere else to go. But all our beds were filled, and I turned the poor lad away.

As I closed the door I wondered what would become of him, and I hoped he had other boys to huddle with somewhere on such a cold winter’s night.

VO:

But I must admit I returned then to my work and didn’t give the boy another thought.

The next day I was walking in the lane beside the house when I passed two men carrying a body between them.

To my great dismay it was the very same lad I had seen just the night before, frozen to death.

VO:

What I saw in that moment was that for every child I helped there were still others out there in desperate need.

I made a decision.

Straight away I had a sign made and put up on the front of the house.

It read: 'No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission'.

I vowed to never again turn a homeless child away.And I never did.

In my lifetime I did all that I could to help the children of London’s slums.

I opened 96 homes altogether, where we helped 8,500 children.

The work I started continues to this day.

Once I was a boy who could think only of what he could do for himself, but I became a man obsessed with how I could best do things for others.

And my life was all the better for that.

Video summary

This short film is for teachers and review is recommended before use in class.

Thomas Barnardo tells the story of his life, descibing the events that led to him setting up schools and homes for London's street children.

The story is told in the first person, and brought to life with a mix of drama, movement, music and animation.

When he discovers the reality of life in London's slums, Barnardo sets up a free school for children: The Ragged School.

However, when he learns that many of the children he teaches have no home at all, he creates the first of many shelters for homeless boys.

One night, with all the beds filled, he turns a child away.

The next day he sees the very same boy frozen to death.

He makes a vow to never again turn a homeless child away, and spends the rest of his life dedicated to doing all he can to help London's poor.

This clip is from then series True Stories.

Teacher Notes

Questions to consider whilst watching the film

Depending on the focus of your lesson, you may wish to ask the following questions after the video or pause the short film at certain points to check for understanding.

- How would you describe Thomas Barnardo as a boy?

- In what ways did he change as an adult?

- How did Barnardo describe the conditions he saw on the streets of the East End of London?

- Why were the children on these streets not at school?

- Why did Barnardo find it hard at first to be a teacher at the ragged school?

- How did Jim Jarvis change the life of Thomas Barnardo?

- Why did Barnardo have the sign ‘No destitute child ever refused admission’ placed on his homes?

Learning activities to explore after the video

History is a subject which can lend itself to a wide range of cross-curricular links. As a teacher, you will have a greater awareness of how this topic may act as stimulus for learning in other subjects. However, the suggestions below relate solely to ways of developing the children’s historical knowledge and understanding.

Key Question: What difference did Thomas Barnardo make to the life of children?

Historical Enquiry

There are two aspects of Thomas Barnardo’s work which could be explored and each would require the pupils to develop their evidential skills, specifically studying visual sources. One topic would be ragged schools and the other, Barnardo’s homes for homeless children. If teachers had the time, both could be covered but if there is only time for one then ideally the latter would be chosen as that is why Barnardo is historically significant.

There were different types of school in Britain at the time and Thomas Barnardo’s ragged school was just one of many. This BBC Bitesize guide has more information about the range of Victorian schools. The National Archives website has a section called Significant Places and this includes an illustration of a classroom in a ragged school from 1853. This picture is full of detail and could form the main basis of a lesson. There is plenty of guidance about using visual images in the classroom. The Historical Association has this guide and the National Archives provides approaches and activities which can be used with their images.

On the topic of Barnardo’s homes, there are fewer resources designed specifically for the primary classroom. However, there are weblinks to some of the resources in the Barnardo archive. BBC Newsround has the photographs of some of the first children to be taken into care by Barnardo’s. Most of the children have two photographs, one before their admission and another a number of years later. The contrast of some, like Herbert John Ransom, could be used as a whole class activity to make inferences about how Barnardo’s helped the children.

On the BBC Newsround site, there are five case studies and the class could be divided into groups to look at just one of these children before feeding back to their peers. The website, given its audience, has been selective about the information on each child and other websites like BBC News have more information, though some of this may be upsetting for children in your class. As a teacher, you will be best placed to gauge the level of detail to give to your class and that in turn will determine the tasks the pupils will be able to do. Your planning should take account of the needs and experiences of any looked-after children in your class. One focus could be the reasons why the child needed to be admitted and another what we know about what happened to them when they left the home. There may be other information, about their health and family, which could be studied depending on the facts the groups are given.

The key question can be answered at two levels. Firstly, from a purely historical perspective, about the Victorian children directly affected by Thomas Barnardo. However, it can also be explored by considering his contemporary significance through his very well known charity. Details of the current work of Barnardo’s is on their website. Again, as a teacher you will need to judge as to how much detail would be appropriate for your class.

Learning aims or objectives

England

From the history national curriculum

Pupils should:

- understand the methods of historical enquiry, including how evidence is used rigorously to make historical claims.

Northern Ireland

From the statutory requirements for Key Stage 2: The World Around Us

Teaching should provide opportunities for children as they move through Key Stages 1 and 2 to progress:

- from making first hand observations and collecting primary data to examining and collecting real data and samples from the world around them.

Links can be made with the other learning areas:

- by researching and expressing opinions and ideas about people and places in the world around us, past, present and future.

Scotland

From the Experiences and Outcomes for planning learning, teaching and assessment of

Second Level Social Studies:

- I can use primary and secondary sources selectively to research events in the past.

Wales

From the new Humanities Area of Learning and Experience

School curriculum design for History should:

- develop historical … source-based skills.

- develop rich content across the time periods, through which learners can develop an understanding of chronology through exploring … the use of evidence.

Principles of progression

Descriptions of learning for Progression Step 2

Enquiry, exploration and investigation inspire curiosity about the world, its past, present and future:

- I have been curious and made suggestions for possible enquiries and have asked and responded to a range of questions during an enquiry.

- I have experienced a range of stimuli, and had opportunities to participate in enquiries, both collaboratively and with growing independence.

- I can collect and record information and data from given sources…

Alexander Graham Bell. video

Alexander Graham Bell tells the story of his life and describes how he invented the telephone.

Florence Nightingale. video

Florence Nightingale tells the story of her life and how she grew up to become a nurse.

Harriet Tubman. video

Harriet Tubman explains how she escaped slavery and then helped others to do so.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel. video

Isambard Kingdom Brunel shares how he became an engineer and tunnelled through Box Hill.

Mary Anning. video

Mary Anning describes how her astonishing fossil finds changed scientific thinking.

Edward Jenner. video

Edward Jenner tells the story of his life and the vaccination against smallpox.

Elizabeth Fry. video

Elizabeth Fry describes how she reformed life for prisoners and their families in prison.

Grace Darling. video

Grace Darling describes the night she and her father rowed out in a boat to save sailors.

Rosa Parks. video

How Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat changed the rules of American society.