ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:I'm going to tell you something about my life.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:My name is Alexander Graham Bell.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:I was born in the year 1847, in Edinburgh.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:To understand where I ended up, you'll need to understand where I started from. So the story I will tell you begins when I was just a boy.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'By the time I was 10 years old, my mother was almost deaf.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'She liked to listen to me playing the piano, although I'm not sure exactly what she heard.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'She would sit beside me, with her hearing tube pressed to the piano, and seemed to like it, even though I didn't really play that well.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'Because of my mother, I was interested from an early age in how sound works.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I spent ages peering inside the piano watching how, when I pressed a key, a little hammer hit some strings, making them vibrate.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'And I saw it was the vibration that made the sound.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I think it was the vibrations too that Mother could pick up through her hearing tube.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'Sometimes, in the next room, my father would be teaching one of his pupils. It was his job to try and help deaf people to learn to speak.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'He'd invented a system that helped them learn how to move their throat, tongue and lips to produce the vibrations to make the different kinds of sounds that went into speech.'

CHATTER

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'When there were people round for tea, and the chatter was whirling around the room, I didn't like the thought of my mother missing out.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'So I tried to help her follow the conversation, by tapping a code out on her arm.'

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'Perhaps because of my mother, I was so glad that I could hear. I was so aware that the world was full of sound.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I would go out and walk sometimes, just to listen.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'And it was like the whole world was vibrating all at once.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I thought if I listened hard enough, I could even hear the sound of moss growing and creeping its way along a fallen tree.'

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I was always tuned in to the sounds things made, and even when I grew up I was still listening.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'But now I had my own ideas too. About how sound worked, and about all the things that might be possible to do with it.'

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:I was itching to try some things out. So my father set my brother, Melly, and I a challenge. To invent a machine that could replicate the human voice.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:A talking machine.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:The idea got me really excited.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'We tried to figure out what it was that made the human voice come out at all.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'We tried to think of the body as a machine, with all the mechanisms needed to cause a vibration to make a sound. But not just any sound, all the different kinds of sounds that make up speech.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'We made something, and it worked!'

MACHINE:Ma ma.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'Well, kind of worked.'

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'When I wasn't thinking about machines, or working on my ideas, I taught deaf children, just like my father did.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I never forgot that some people, like my mother, could hear very little or nothing at all.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'And teaching them how to make sounds spurred me on. And I had so many ideas about how to make machines that could manipulate sound.'

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:Then a chance came along for me to try out some of my ideas.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:I was asked to find ways to improve the telegraph machine.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:The telegraph machine was a relatively new invention, used to send messages from one place to another.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:Before the telegraph, messages had to be hand-written and sent by horse and cart. Well, this was so much quicker.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:It sent messages from one place to another by taking the words of the message and turning them into a code, like Morse code, which could be sent down an electrical wire.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:At the other end,

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:the code was received and translated back into words again.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'But the big drawback was you could only send one message at a time. And it had to be sent from the telegraph office, which often meant there was a very long queue.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'And when the messages were received at a telegraph office somewhere else, they had to be printed off, one at a time, and delivered to the right address.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'It was a clever system, but sending one message at a time was simply too slow.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I was working on how to make the telegraph machine better, but I kept coming back to a different idea.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'What if, rather than turning a message into a code, and then sending that code along an electrical wire, then turning it back into words again,

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'what if you could send the sound of a human voice so that one person could simply speak to another, even if they were far away?

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I had an idea that you could use electricity to send sound itself along a copper wire.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'But I wasn't quite sure how to build it.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I got a man called Watson, who was good with electricity, to help me out.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'We rented two rooms, one next to the other.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'And together, we came up with a contraption that might just work.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'It had a mouthpiece, or transmitter, to speak into, then using a dangerous liquid called acid, the sound would be urned into electricity, travel along a copper wire, and be turned back into sound again at the other end, at the receiver.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'We had something that we thought might work, and we got ready to try it out.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'But just then, at the crucial moment,'

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:Come in here, Watson. I need you!

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I spilt acid on my trousers. It was burning my leg.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'Come in here, Watson. I need you!'

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'To my utter amazement, Watson had heard me, the machine had worked!

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:'I was so excited, I almost forgot the burning sensation on my leg.'

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:In that moment, the telephone was born.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:It needed more work, but soon I was ready to show people what I had invented.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:It caught on, and it was a great success.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:Amazing to think that the device that we rigged up between those two rooms was the first ever telephone.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:And now, in your world, there are more than five billion of them.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:What had started with me playing piano for my mother and peering inside to see how it worked,

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL:led me down a road that ended in an invention that, quite frankly, the world now simply couldn't do without.

Video summary

This short film is for teachers and review is recommended before use in class.

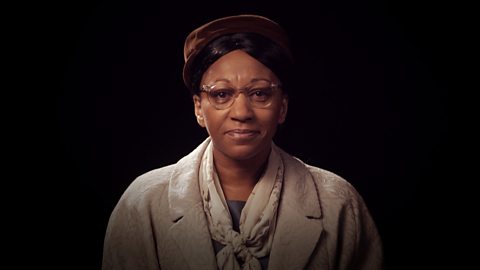

Alexander Graham Bell tells the story of his life and describes how he invented the telephone.

Told in the first person, and brought to life with a mix of drama, music and animation.

As a boy, Bell was fascinated by sound; he grew up with a mother who was almost deaf, and a father who helped deaf people to speak.

He and his brother came up with a machine that could (almost) replicate the human voice.

When he was asked to work on ways to improve the telegraph machine, Bell hit upon another idea.

He thought that rather than sending a code along an electrical wire, it might be possible to send the actual sound of a human voice along a wire.

With the help of a man called Watson they built a device that just might work.

An accident proved him right, and the telephone was born.

This clip is from the series True Stories.

Teacher Notes

Questions to consider whilst watching the film

Depending on the focus of your lesson, you may wish to ask the following questions after the video or pause the short film at certain points to check for understanding.

- Why was Bell interested in how sound works from an early age?

- What challenge was set by his father? Was Bell successful in meeting that challenge?

- What did Bell do before he became an inventor?

- What was the telegraph machine and why was Bell asked to improve it?

- Why did Bell need the help of Watson?

- How did Bell’s first telephone work?

- What were the first words spoken by Bell on his telephone?

- Do you agree with Bell when he said that ‘the world now simply couldn't do without’ the telephone?

Learning activities to explore after the video

History is a subject which can lend itself to a wide range of cross-curricular links. As a teacher, you will have a greater awareness of how this topic may act as stimulus for learning in other subjects.

For example, this clip could be used to provide the content for a group role-play activity on the life of an inventor, such as Alexander Graham Bell. The groups could be given a storyboard while watching the film to plot each key stage of an inventor's life. Pupils could then use this to prepare and rehearse a play on the making of an inventor and perform to the class. This would help pupils to empathise with a historic character and engage with the finer details of the era.

The video could also be used to develop the children’s historical knowledge and understanding. It is possible for there to be some follow-up activity solely on Bell himself, but for a full lesson it is likely that the study will need to move beyond one person and explore the subsequent history of telephones. If you wish to focus on Bell, this Bitesize guide has further information and visual sources about Alexander Graham Bell and it raises the interesting question, 'Was Alexander Graham Bell really the first person to invent the telephone?'

Key Question: How has the telephone changed over 150 years?

Chronological understandingThere are opportunities here to develop the pupils’ chronological understanding and this activity will provide an overview for the main activity below. An internet search will provide timelines and images showing the evolution of the telephone over the last 150 years, which can be used for an activity in which pupils sequence a wide range of images along a timeline, and identify some of the key turning points in terms of telephone design.

Concept of change and continuity

With the whole class having an overview of the history of telephones, the pupils could then research the key developments. Either one group could look at one development, or within a group, each individual pupil could research a different one. The topics for exploration could be as follows:

- The first telephones

- The public call box

- The move from switchboard operation to subscriber trunk dialling

- Developments in the home landline telephone: the rotary dial to push button; the move to cordless telephones

- The first mobile phones

- The smartphone

For each of these topics, the pupils would need to identify how each innovation improved the telephone. As a concluding plenary activity, once the class has knowledge of each of the developments, they could evaluate which is the most significant improvement.

Curriculum Notes

Learning aims or objectives

England

From the history national curriculumPupils should:

- develop a chronologically secure knowledge and understanding of British, local and world history, establishing clear narratives within and across the periods they study.

- understand historical concepts such as continuity and change.

Northern Ireland

From the statutory requirements for Key Stage 2: The World Around UsPupils should be enabled to explore:

- Change over time in places.

Teaching should provide opportunities for children as they move through Key Stages 1 and 2 to progress:

- from identifying similarities and differences to investigating similarities and differences, patterns and change.

- from sequencing events and objects on a time line in chronological order to developing a sense of change over time and how the past has affected the present.

Links can be made with the other learning areas:

- Language and Literacy: researching and expressing opinions and ideas about people and places in the world around us, past, present and future.

Scotland

From the Experiences and Outcomes for planning learning, teaching and assessment ofSecond Level Social Studies:

- I can investigate a Scottish historical theme to discover how past events or the actions of individuals or groups have shaped Scottish society.

- I can discuss why people and events from a particular time in the past were important, placing them within a historical sequence.

Wales

From the new Humanities Area of Learning and Experience

School curriculum design for History should:

- develop rich content across the time periods, through which learners can develop an understanding of chronology through exploring … change and continuity.

Principles of progression

Descriptions of learning for Progression Step 2

Enquiry, exploration and investigation inspire curiosity about the world, its past, present and future:

- I have experienced a range of stimuli, and had opportunities to participate in enquiries, both collaboratively and with growing independence.

Human societies are complex and diverse, and shaped by human actions and beliefs:

- I can identify aspects of life in my community that have changed over time.

Florence Nightingale. video

Florence Nightingale tells the story of her life and how she grew up to become a nurse.

Harriet Tubman. video

Harriet Tubman explains how she escaped slavery and then helped others to do so.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel. video

Isambard Kingdom Brunel shares how he became an engineer and tunnelled through Box Hill.

Mary Anning. video

Mary Anning describes how her astonishing fossil finds changed scientific thinking.

Edward Jenner. video

Edward Jenner tells the story of his life and the vaccination against smallpox.

Elizabeth Fry. video

Elizabeth Fry describes how she reformed life for prisoners and their families in prison.

Grace Darling. video

Grace Darling describes the night she and her father rowed out in a boat to save sailors.

Rosa Parks. video

How Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat changed the rules of American society.

Thomas Barnardo. video

Thomas Barnardo tells the story of setting up his first home for London's street children.