In 1917 the situation on the Western Front had become bleaker than ever.

Britain’s allies were tottering.

There was mutiny in the French army while Russia, torn apart by revolution, was about to pull out of the War.

And the death toll went on rising, already more than half a million British dead since the start of the War. Even decorated war heroes were now wondering what they’d risked their lives for.

In 1917 one of them, the poet Siegfried Sassoon went public with his doubts about the war.

In the trenches his men had known Lieutenant Sassoon as Mad Jack for his astonishing fearlessness and he’d won a Military Cross for bravery, but now he was denouncing the whole thing.

“The war upon which I embarked as one of defence and liberation” he wrote “has become a war of aggression and conquest. I am protesting against the political errors for which the lives of fighting men are being sacrificed and against the callous complacency with which those at home regard agonies they do not share.”

From a decorated war hero this was incendiary stuff.

Sassoon risked court-martial, imprisonment, even execution, but the Generals were cleverer than that, they pronounced him mad and sent him here to a military hospital called Craiglockhart.

Sassoon was surrounded by men suffering from the condition called Shell Shock. This War of endless artillery bombardment wasn’t only killing and maiming soldiers, it was sending them mad.

At first doctors thought it was a physical condition, concussion caused by exploding shells.

Treatment was often brutal; some doctors used solitary confinement and electric shock treatment to try to snap their patients out of it.

But then they began to understand something of the stress of life in the trenches, the lack of sleep, the shattering noise, the sight of so much death and mutilation.

As one lieutenant put it, “quite apart from the number of people blown to bits, the explosions were so terrible that anyone within a hundred yards was liable to lose their reason”.

At Craiglockhart doctors were pioneering a radical new approach to shell shock.

Dr William Rivers believed that patients were repressing the terrifying experiences they’d had and that in order to get better they needed to talk about them.

In 1917 Rivers’ work was ground breaking. But Craiglockhart’s most famous patient, the anti-war Lieutenant Sassoon, wasn’t suffering from shell shock and he realised that unless he gave up his protest and returned to the Front he’d be stuck here forever.

After three months Sassoon was restless. He hadn’t changed his anti-war views, but he chose solidarity with his soldiers over private principles. As he wrote when he returned to the Western Front “I’m only here to look after some men”.

Siegfried Sassoon’s protesting voice had been silenced, but his poetry remained clear and forceful.

In 1918 he wrote, “You smug faced crowds with kindling eye, who cheer when soldier lads march by, sneak home and pray you’ll never know the hell where youth and laughter go.” Unlike many of his friends, including fellow writer Wilfred Owen, whom he’d met at Craiglockhart, Sassoon survived the War and died in 1967.

Video summary

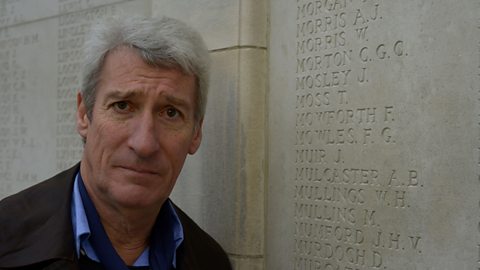

Jeremy Paxman explores the poetry of Siegfried Sassoon, mental health problems suffered by soldiers in the First World War, shell shock and the low morale caused by the huge British death toll.

Poet Siegfried Sassoon, a decorated war hero, expressed doubts about the purpose of the war, and the complacency of the commanders.

Instead of being court-martialled, he was declared mad and sent to Craiglockhart Hospital, a newly-established treatment centre for soldiers with mental health problems.

Paxman explains some of the treatments attempted by doctors who didn’t understand the condition. At Craiglockhart, the revolutionary idea of getting soldiers to talk about their traumatic experiences was tried.

We hear how Sassoon returned to the Front after three months out of solidarity with his men.

Teacher viewing recommended prior to use in class.

Teacher Notes

Key Stage 3:Use this clip to provide context for a study and analysis of war poetry.

Key Stage 4 / GCSE:Use as a comparative tool in the study of medicine through time. Use as comparative evidence to be contrasted with the drawings of Otto Dix. Other examples too may broaden the analysis. Also useful to provide context about war poetry.

This clip will be relevant for teaching History. This topic appears in at KS3 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and OCR, Edexcel, AQA and WJEC/Eduqas GCSE/KS4 in England and Wales and CCEA GCSE in Northern Ireland.

How Britain declared war in WW1. video

Jeremy Paxman explores the declaration of war after Germany invaded Belgium in 1914.

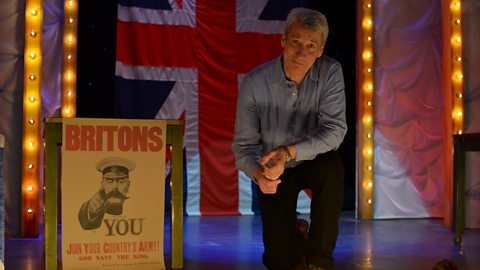

Your country needs you! video

Jeremy Paxman explains Lord Kitchener's iconic recruitment PR campaign of WW1.

Crushing defeat in the first battle of WW1. video

Jeremy Paxman explores how Britain suffered defeat at the Battle of Mons.

The Home Front. video

Jeremy Paxman explains how German u-boats crippled the country and led to rationing and the Home Front.

Treating Indian soldiers at Brighton Pavilion. video

Jeremy Paxman explains how a former royal residence became a hospital for injured soldiers in WW1.

Air raids and the bombardment of Britain in WW1. video

Jeremy Paxman explains the unprecedented bombardment of Britain in World War One.

The dangerous jobs of women in WW1. video

How women entered the workforce and took up dangerous roles to support the war effort.

How the Britain turned the tide in 1918. video

How the British workforce, the Home Front and the USA joined together to fight back against the German advance in 1918.

1918: the end of the war and Remembrance Day. video

Jeremy Paxman describes the end of the First World War.