By June 1918 the balance of power in The First World War had shifted violently towards Germany.

Having made a peace with an exhausted Russia, Germany could now pour troops onto the Western Front.

They now outnumbered the allies by over 200,000 men and they were massing for an attack they believed would win the War.

In the first five hours of the great Spring Offensive over a million shells were fired into British lines.

In a conflict where success was measured in yards the Germans advanced forty miles in a single day. In his diary The Secretary to The British War Cabinet wrote, “The Germans are fighting better than the allies. I cannot exclude the possibility of disaster.”

The British Army Commander Sir Douglas Haig made one last desperate rallying call.

“Every position must be held to the last man, there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause we must all fight on till the end.”

The call to arms would be heard well beyond the trenches.

The Home Front couldn’t afford to buckle either, the country’s war machine had to be kept running.

Prime Minister Lloyd George had once called the British workforce the least disciplined in Europe. Could they be relied upon at this moment of crisis?

Anyone searching for cracks in the nation’s resolve might have come here to the South Wales Coalfield.

In 1918 this place was considered The Wild West of industrial relations. The Welsh miners had been a thorn in the government’s side throughout the War, calling strike after strike.

This, the finest steam coal in the world, was a vital part of the War effort.

It drove the foundries, the forges, the explosives factories, it powered the warships and it gave the men who extracted it tremendous power.

By 1918 there’d already been trouble in the pits over the practise of combing out, that was forcing men out of vital protected industries like this and into the Army.

With the country now facing the real possibility of defeat further industrial unrest could have been catastrophic.

In fact just the opposite happened. When it came to it even the most bolshie miner wasn’t prepared to see Britain lose the War. When asked to pull together for the sake of the troops the response of the British workforce was emphatic. In all industries strikes were suspended and people even turned out to work extra shifts.

On the Clyde thousands of ship builders gave up their Easter holiday to keep working.

Recruiting offices saw a rush from men in protected jobs coming forward to enlist.

The Minister for Munitions, Winston Churchill, could scarcely believe his eyes, “The response to our appeal to work over the holiday”, he said “was excellent, indeed almost embarrassing”.

At the very worst point in the War the Home Front had not only held, it had risen to the challenge. The forces didn’t lack for supplies, for ammunition or for weapons; this was one time in the nation’s history when we really were all in it together.

In Germany it was a very different story. With German ports blockaded by the British Navy the country was being slowly starved out of the War.

Angry crowds took to the streets demanding peace.

Anti-war strikes crippled German industry. When a horse dropped dead in a Berlin street the locals fell on it for meat.

On the battlefield the huge German Spring Offensive had failed to break the allies, if anything it had broken the Germans. Their plan had devoured men and ammunition, troops were left exhausted, demoralised and lacking supplies and as the German war machine began to fail Britain’s was at full throttle.

By the summer of 1918 weapons were rolling off the production lines in greater numbers than ever before.

The previous year The United States had agreed to enter the War; now American troops had at last arrived and were fighting with the allies. The tide had turned, though victory would come sooner than anyone imagined.

Video summary

With a German victory in sight in the spring of 1918, a huge effort by the British workforce helped to turn the war in the Allies favour, by keeping the troops supplied with coal and munitions.

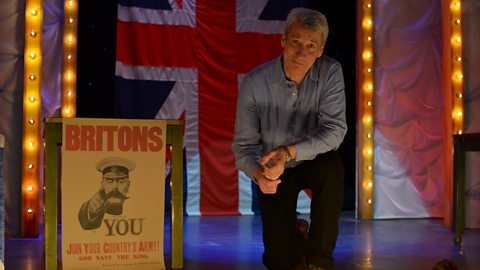

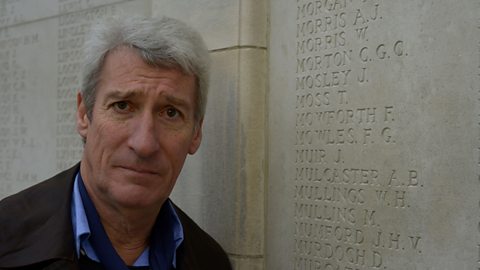

Jeremy Paxman reads the words of British army commander General Sir Douglas Haig in April 1918, telling his men to fight on until the end, as we see archive footage of battlefield devastation.

He visits a mine in South Wales, and explains how British workers suspended strikes, worked through their holidays and volunteered for extra shifts to support the war effort.

Munitions workers, miners and shipbuilders all took part in this extra help for the troops’ supply chain, and men in protected industries volunteered themselves to fight.

Whilst the home front in Britain pulled together, Germany experienced strikes, demonstrations against the war and hunger due to Allied blockades, all of which helped diminish German morale.

The arrival of US troops to support the Allies is also discussed as a factor in turning the tide of the war.

Teacher viewing recommended prior to use in class.

Teacher Notes

Key Stage 3:Use as an access point to the idea of protected jobs in the war. Might be used as a decision making task to include conscientious objectors, in identifying those who were not involved in direct combat._

GCSE:Use as a prelude to the post war debate of was Britain a “Land fit for heroes” to provide context for continuing working class discontent in post war Britain.

National 5/ Higher:Use as an introduction to the effect of the war effort at home on the course of the war and changing industrial relations. Students could concentrate on industries in their local area or more general Scottish examples. What part did the chosen industry play? What scale of effort was involved? what were relations between workforce and management like at this time? How different was this industry before, during and after the war?

This clip will be relevant for teaching History. This topic appears in at KS3 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and OCR, Edexcel, AQA and WJEC/Eduqas GCSE/KS4 in England and Wales and CCEA GCSE in Northern Ireland. It also appears in National 5 and Higher in Scotland.

How Britain declared war in WW1. video

Jeremy Paxman explores the declaration of war after Germany invaded Belgium in 1914.

Your country needs you! video

Jeremy Paxman explains Lord Kitchener's iconic recruitment PR campaign of WW1.

Crushing defeat in the first battle of WW1. video

Jeremy Paxman explores how Britain suffered defeat at the Battle of Mons.

The Home Front. video

Jeremy Paxman explains how German u-boats crippled the country and led to rationing and the Home Front.

WW1 poetry and shell shock. video

Jeremy Paxman looks at the mental health problems suffered by poet Siegfried Sassoon and soldiers in the First World War.

Treating Indian soldiers at Brighton Pavilion. video

Jeremy Paxman explains how a former royal residence became a hospital for injured soldiers in WW1.

Air raids and the bombardment of Britain in WW1. video

Jeremy Paxman explains the unprecedented bombardment of Britain in World War One.

The dangerous jobs of women in WW1. video

How women entered the workforce and took up dangerous roles to support the war effort.

1918: the end of the war and Remembrance Day. video

Jeremy Paxman describes the end of the First World War.