While we exult in black Britons ongoing success in sports, music, fashion and the NHS today, discrimination still blights lives.

Introduction

Note: As mentioned in the black African chapter – it is problematic to group Caribbean and African audiences by the homogenous label of ‘black’. Nuance is also needed for the black Caribbean label, a term applied to many from the West Indian islands, which are vastly different and unique. Furthermore, while we are specifically talking about the black Caribbean population in this write up, we must be mindful that the Caribbean islands are also home to the Indian and Chinese communities, which dates back to the history of slavery.

We cannot deny the positive presence that the black Caribbean population has had on Britain and British culture. We have undoubtedly benefited from the hard work and dedication that black Caribbeans have given to the NHS, public transport and manufacturing industries after the Second World War.

We have borrowed and adapted legacy sounds of the Caribbean including reggae, dub, soca which has transformed and shaped our music industry and cultures today.

Notting Hill Carnival is one of the biggest street festivals in the world, established after the race riots in the 50s. While Carnival is a wonderful and colourful celebration of emancipation, Britain’s long and cruel history of slavery has had a lasting impact that is still largely felt by the black Caribbean population in every facet of their daily lives today. Despite this group being the most integrated out of all ethnic minority groups in terms of having a ‘British way of life’.

Read on to find out more about this incredibly diverse community.

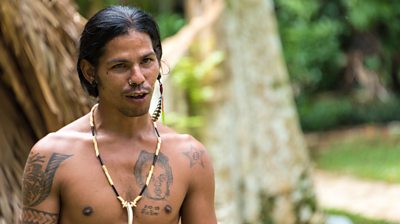

Prior to European colonisation of the Caribbean Islands, the islands were inhabited by the Ciboney, Arawak and Carib peoples from mainland America. The Spanish were the first Europeans to claim land on the Caribbean islands.

History

The Spanish were the first Europeans to claim land on the Caribbean islands. Christopher Columbus was the first European to arrive in the Bahamas and he labelled the indigenous people ‘Indians’ believing he had reached Asia. The islands since have been referred to as the ‘West Indies’.

Despite the Arawak people welcoming the newcomers, they were made to work in the fields and mines, often being worked to death. European invasion also came with deadly diseases (measles and flu) against which the indigenous people lacked immunity. The Caribs resisted European settlement and many died defending their lands.

After colonisation by the Spanish in the 15th century, a system of sugar planting and enslavement evolved. Despite Spain’s initial colonisation, the slave trade was dominated by France, Britain and Portugal. It is estimated that between the 15th and 19th centuries up to 15 million people were abducted and forcibly transported from Africa to the Caribbean. As the plantations grew and became more reliant on enslaved workers, the populations of the Caribbean colonies changed, so that people born in Africa, or their descendants, came to form the majority.

Although the British slave trade officially ended in 1807 which made the buying and selling of slaves from Africa illegal; slavery itself was not fully abolished until the Slavery Abolishment Act of 1833 came into place.

The Act of 1833 saw compensation given by the British government to slave owners not to free slaves but to line the pockets of 46,000 British slave owners as ‘recompense’ for losing their ‘property’. This cost the government £20 million (approximately £20bn today) a staggering 40% of its budget in 1833. The cost was so high that loans the government took out to fund it were only just paid off in 2015.

The slaves, however, were not compensated and faced extreme poverty in the monoculture sugar economies that Britain had set up in the Caribbean.

It is also worth noting that rarely do people know of the Caribbeans of Indian and Chinese descent. Indian Carribeans have been recorded as the largest ethnic group in Trinidad and Tobago and in Guyana today. After the ‘abolishment’ of slavery, from 1834 onwards, plantation owners in the Caribbean desperately needed a way to continue to profit from the manufacture and sale of sugar products.

As such, the British, French and Dutch colonisers established a system of indentureship to exploit cheap resources by allowing labourers to move between plantation colonies for a contracted period of around five years. The indentured workers were recruited from India, China and from the Pacific. And while they were promised a better way of life, the reality was far from it.

The labourers were exploited and suffered from ill treatment and abuse. This system came to an end around 1917 when the British government banned the transportation of Indian servants and many of the Chinese who were brought over did not return to China because they were not entitled to a free return passage or any assistance. This is an important nuance to note about the Caribbean identity and also explains the influences in Caribbean food.

The Slavery Abolishment Act of 1833 saw compensation given by the British government to slave owners not to free slaves but to line the pockets of 46,000 British slave owners.

It was during World War I when the first wave of mass immigration of the black Caribbean population to Britain began. Black Caribbeans arrived to join the armed forces and to work in the war industries and merchant navy. Sixteen thousand men and women from the Caribbean voluntarily enlisted.

During the Second World War, again, many from the Caribbean colonies signed up in the sense of patriotic duty despite resentment of colonial rule.

“We were British subjects and that was something to be proud of.” -Victor Brown, a Jamaican who fought with the Merchant Navy. [2015]

Like many other ethnic minorities that fought in the war, their stories are often forgotten. In November 2014 a memorial dedicated to African and Caribbean soldiers was unveiled in Brixton, south London, where many ex-servicemen settled after the war.

In June 1948 the Empire Windrush ship arrived in Essex carrying hundreds of people from the Caribbean (primarily Jamaica, Trinidad, Tobago and other islands) many of whom were children.

The 1948 Act gave Commonwealth citizens free entry to Britain as the country had opened its doors to former colonies to seek help in labour shortages after the war. black Caribbeans played a significant role, along with other immigrants in rebuilding Britain, working in sectors including manufacturing, public transport and the NHS. By 1954, more than 3,000 Caribbean women were training in British hospitals.

People of Caribbean heritage continue to make up a significant proportion of today’s workforce and the NHS is the biggest employer of people from an ethnic minority background in Europe.

At the time, many of the Caribbean islands were still British colonies including Jamaica, Barbados and St Lucia and Caribbean children were taught that they were British citizens. Britain was referred to as ‘The Motherland’ or ‘Mother Country’. As such, the Windrush Generation thought they would be welcomed with open arms, instead they were met with racism and discrimination. Many of them found it difficult to find accommodation and jobs.

Vicious and racist attacks on the Caribbean community in the Notting Hill area of London took place in 1958. The Mangrove Restaurant opened in Notting Hill in 1969 and was an important meeting space for the black community. It was repeatedly raided by police, on grounds of drug possession, despite a lack of evidence. In response the black community staged a protest on the 9th August 1970 against the unjust police treatment.

Violence between police and protesters led to the arrest of nine people (including the owner Frank Crichlow) who become known as the ‘Mangrove Nine’. The trial lasted 10 weeks with all nine acquitted of the main charge of inciting a riot. The trial was highly significant in being the first judicial acknowledgement of racial prejudice in the Metropolitan Police, which paved the way for the 1976 Race Relation Act and led to the founding of the Commission for Racial Equality.

The migration influx ended with the 1971 Immigration Act and Commonwealth citizens already living in the UK were given indefinite leave to remain.

The Caribbean is made up of as many as 7,000 thousands islands– of which there are 26 countries that includes 13 independent nations, as well as territories of France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Culture

The Caribbean population, longer established and more fully integrated with a British way of life, has assimilated more successfully than perhaps any other immigrant group of modern times.

For young black people born in Britain the rates of intermarriage for both men and women are high: nearly 50% and 35% respectively, compared with a rate of just 7% and 6% for Indian men and women.Which means that fewer than half of British black Caribbeans have partners who are also black Caribbean.

Generally the older generations have a relaxed attitude towards life and are particularly happy to take life as it comes.

For younger generations that have grown up in the UK, blackness and Britishness are not mutually exclusive, but rather both are part of their overall identity, though older generations do worry about the dilution of culture.

CARIBBEAN DIVERSITY

Not a single Caribbean island looks like any other in terms of its ethnic composition. And that is before you start to touch the question of different languages, different cultural traditions, which reflect the different colonising cultures. Diversity is the most important keyword when dealing with the Caribbean. There is diversity in ethnic groups, currencies, politics, beliefs and more.

The Caribbean is made up of as many as 7,000 thousands islands– of which there are 26 countries that includes 13 independent nations, as well as territories of France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Due to the size of the Jamaican population in the UK, Jamaican influences tends to dominate Afro- Caribbean culture across the UK. But it’s worth noting that other islands are proud to retain their own identity and island-specific community centres exist to enable traditions to be preserved.

That said, there is a strong sense of pride in the Caribbean heritage and some do see the value in the ‘Caribbean identity’ as a whole.

Jamaica itself is richly diverse in ethnicity with today’s population consisting predominantly of descendants a smaller number of mixed African and European descent and those who can trace their ancestry back to India, China, the Middle East, Portugal, Germany and the UK. The Jamaican motto ‘Out of Many One People’ speaks to this diverse identity but equally the Caribbean overall.

“A big part of carnival was the mimicking of enslaved people, white men basically would blacken their faces, put on tattered clothes and imitate enslaved field labourers.”

CARNIVAL

Following the ‘Mangrove Nine’ arrests in 1958, the annual Notting Hill Carnival was created by the community in 1959. Notting Hill Carnival in London celebrates Caribbean culture every August Bank Holiday and is one of the world’s largest street festivals. The festival comes to life with steel bands, street food, dancing and art followed by a traditional J’ouvert parade taking place early on Sunday morning.

J’Ouvert originated with French settlers and their introduction of masquerade balls to the Caribbean in 1783. Carnival emanates from the struggle of black Caribbean people. Banned from participating in their masters’ Carnival celebrations which were largely a mockery of the enslaved, slaves held smaller carnivals in their backyards.

“A big part of carnival was the mimicking of enslaved people, white men basically would blacken their faces, put on tattered clothes and imitate enslaved field labourers.” - Dr Meleisa Ono-Georg, Director of Student Experience at the University of Warwick [2020]

Once liberated from slavery in 1838, slaves began participating in Carnival, blending in their own rituals. Carnivals also take place across Manchester and Liverpool. The annual event is a significant part of identity and culture for the black Caribbean community and Notting Hill Carnival is widely celebrated by people from all islands. Some parents are keen to ensure that their children retain their cultural heritage.

“I try to get them involved with the Carnival... We are involved in the food and the children play ‘mas’ and my daughter mocks me when I am dancing. I took my costume to a cultural day at their school and everyone loved it but they are becoming British. They are proud of their Trinidadian heritage but they see themselves as Londoners, British.”

LANGUAGE

There are varieties of English spoken in the Caribbean, a result of the crossover of languages that emerged and evolved as a result of the slave trade. When thousands of slaves were transported to the Caribbean, a number of pidgin languages developed. This is a linguistically simplified language that emerges naturally when speakers of two or more languages need to understand each other.

On the colonial plantations the language imposed on slaves (who spoke a variety of ethnic African languages) by their owners was English. They found it difficult to communicate with each other so over time this resulted in the appropriation of various features of English which they combined with some features of their various African languages.

The pidgin language then developed into a more complex language and became the first language of a community which is called ‘a creole’ or ‘a patois.’

This has resulted in nearly every Caribbean island having its own local patois or creole that locals use primarily to speak to one another. And they all greatly vary from island to island depending on which country conquered the island.

Whilst English for some is the first language, a patois or a creole is a strong influence in most homes especially first generation.

MUSIC

There has been no doubt that Caribbean culture has had a significant impact on British culture and music. Many of the styles we listen to today have roots in Caribbean London.

Soca (Soul of Calypso) was coined by artist Lord Shorty in an effort to revive traditional Trinidadian and Tobagan calypso music in the 70’s. By the 1980s, soca had evolved into a range of styles and it was popular in Britain to sample calypso and other Caribbean beats and rhythms into tracks. This style of sampling continued to inspire London pop artists in the years to come, and lay the foundations for many electronic styles such as dancehall, UK garage, jungle, ragga and hip hop.

As noted in the black African section, Grime is one of the spaces where Africans and Caribbean people are coming together and these black influences are inspiring modern black history of African and Caribbean fusion.

It’s also worth noting that rap music and hip hop originally born out of America form a huge part of black culture but it is greatly misunderstood. While media can portray rap music as negative, it can overlook some of the issues that the black community and other marginalised communities across the world face. School counsellors, psychologists, and social workers are now integrating hip hop within mental health strategies.

There is also lovers rock, a style of reggae music noted for its romantic sound and content with its roots in the rocksteady era and early days of reggae. In the 1970s and 80s its prominence and influence in London rose. Janet Kay and Carol Thompson were some of the most influential British lovers rock artists at the time. The genre is also said to have influenced British pop and rock acts such as The Police, Culture Club and Sade.

F--- the police comin’ straight from the underground/ a young n---- got it bad cause I’m brown/ and not the other color so police think/ they have the authority to kill a minority.

FAMILY

Family culture is important in black Caribbean culture. Respect for the elders and learning is paramount; elders have knowledge and wisdom gained through experience of life so their role is pivotal in teaching children respect and principles. Parental responsibility is supported by the extended family and often neighbours. So whereas some children are growing up in a one parent household, the notion of single parents is not an issue as in the UK, as neighbours and extended family alike help with parenting.

Statistically speaking, 65% of black Caribbean children are raised by one parent – nearly always the mother according to an Equality and Human Rights Commission report in 2011. The family unit sets this group slightly apart from other ethnic groups.

However, it’s important we address the nuances here as it is particularly important when it comes to media representation and stereotyping where real life experiences aren’t presented correctly.

Miranda Armstrong, a PhD researcher and Associate Lecturer in the Sociology Department of Goldsmiths College, University of London states that the single-parent stigma is often cited as a cause of violent crime, creating more harmful stereotypes.

Tracey Reynolds author of Caribbean Mothers: Identity and Experience in the UK also states that regardless of whether black children live in lone-mother or married/partnered households, the vast majority are being raised in loving, caring and stable family environments. So while strong, black, single parent, mothers are definitely part of the Caribbean family unit, it is worth noting that this is generational and many of the first generation grew up in the average 2.4 size household.

RELIGION, COMMUNITY AND CARE

Predominantly this is a majority Christian group and church plays a fundamental role in the lives of the black Caribbean community, in particular for the older generation who attend regularly to stay connected with their peers.

Caring for the community is a big part of Caribbean culture. Aside from churches, community centres play an important role in keeping these community ties and cultures alive and provide a space where people can get together and talk informally through community events.

The strength of community ties means that attitudes towards entering a ‘care home’ are alien. Older females, some of whom have spent their lives working as care assistants or nursing older people in British hospitals resist this prospect. There is an unwritten rule in families that children will look after the parents should they come to need dedicated care. This also extends towards disabled care, black Caribbeans see this as their responsibility and families typically play an important role.

Although there are distinct African and Caribbean communities there is also a common black experience based on living in London. The barber shop/hairdresser is one of those common experiences and serves as a bastion communal space for young black men across a number of generations. The barbershop is a place to be vulnerable, talk about issues of importance in the community and plays a significant part in the identity and mental health of black men.

Media Portrayal

As media portrayal and stereotypes follow the categorisation of ‘black’, we’d encourage you to read the black African chapter too. We’ve focused on different angles in both chapters. Where possible, we have tried to be specific about information that pertains to the black Caribbean population.

The Real McCoy in the 1990s, was a real second generation comedy for Caribbean people. A prime slot on BBC Two at the time brought black comedy to the masses and recently the BBC have brought it back on to BBC iPlayer.

This was the first time where a virtually all non-white cast and production team was given the freedom to produce a show in an unapologetically black way. The show is full of political gags – on slavery, racism and multicultural incomprehension that still ring true today. Similarly, Desmond’s which aired on Channel 4 in 1989 was positively received by audiences.

We are seeing improvements in TV over the last 10 years in terms of more diverse appearances on screen but more can still be done. In Ofcom’s Representation and Portrayal of Audiences on BBC television research, many black African and black Caribbean participants were critical of portrayal falling into distinct negative types: the drug-dealing criminal; dysfunctional families with absent fathers and struggling single mums; and the joker masking shortcomings. This was also echoed in BBC’s own research,

“Aspects of my identity that I feel are not identified on TV are of successful single mothers. Successful black women with a soft external and internal view. Struggles single mothers go through on a day to day basis. But in terms of low-income families. Rather than portraying individuals on benefits it would be nice to see hard working individuals who are also on benefits but struggle due to life circumstances and a look into these factors such a universal credit, mental health, being carers, childcare struggles and so on.” -F, 18-34, C2DE, Mixed Race White /Black Caribbean, Bristol [2020]

In the 2011 UK Film Council report it was felt that there should be more black people in pivotal roles really serving a purpose. 72% also agreed with the statement ‘roles for minority groups too often have no depth and are poorly written’.

Stereotyping in the form of sweeping Jamaican generalisations also omits the diversity of this population and remembering Jamaica too is incredibly diverse in terms of ethnicity) and therefore they do not all sound ‘Jamaican’.

“Thinking the Caribbean is a #reggaeculture is simply ignorance. Pretty much, you are saying that the entire Caribbean is Jamaican.

In Ofcom’s Representation and Portrayal of Audiences on BBC Television research in 2018, the report stated that there is permission in common to push portrayal boundaries and play with stereotypes if the underlying sentiment feels authentic. But while audiences felt that comedy has the power to explore identity and expose tensions, it can also exploit them.

In the black African chapter, we covered the stereotypes that pertain to black men. Female portrayal is a cause for concern too.Mammies (submissive maids that support the white family), Jezebels (sexy) and Sapphires (sassy and angry) are three main stereotypes all of which have stemmed from slavery. The ‘angry black woman’ trope dates back to 19th Century America, when minstrel shows, which involved comic skits and variety acts, mocking African Americans became popular.

Octavia Spencer has played a maid, nurse or cleaner a total Of 21 times, including in two of her three Oscar-nominated performances.

These stereotypes have also evolved to include the welfare queen and the sassy best friend.

We just pop up as best friends of white needs. When we were on set it was almost like they were saying to give us more sass, give us more attitude. I absolutely was complicit in the propaganda of anti-blackness.- Babirye Bukilwa, An Actor, Poet And Writer Based In London

What we are presented with is a reductive story that denies the real experiences of black women.

“The welfare queen stood in for the idea that black people were too lazy to work, instead relying on public benefits to get by, paid for by the rest of us upstanding citizens. She was promiscuous, having as many children as possible in order to beef up her benefit take. It was always a myth— white people have always made up the majority of those receiving government checks, and if anything, benefits are too miserly, not too lavish. But it was a potent stereotype, which helped fuel a crackdown on the poor and a huge reduction in their benefits, and it remains powerful today.”

In an article about ‘Digital Blackface’, Lauren Michele Jackson says that black culture is often associated to exaggerate behaviours.

“When we do nothing, we’re doing something, and when we do anything, our behavior is considered ‘extreme’. This includes displays of emotion stereotyped as excessive: so happy, so sassy, so ghetto, so loud. In television and film, our dial is on 10 all the time — rarely are black characters afforded subtle traits or feelings.”

Jackson’s article highlights the issues about how these stereotypes of black people, in particular women, are now also at the heart of online culture. Reaction GIFs are often used as part of modern day communication to summarise universal situations and emotions that we all can relate to and the reoccurring use of black faces is problematic in perpetuating the same stereotypes and associated ‘extreme’ behaviours and emotions.

For while reaction GIFs can and do every feeling under the sun, white and non-black users seem to especially prefer GIFs with black people when it comes to emitting their most exaggerated emotions. Extreme joy, annoyance, anger and occasions for drama and gossip are a magnet for images of black people, especially black femmes.

A Shift in Media Portrayal

We are starting to see shows that attempt to combat female stereotypes - Scandal, How to Get Away with Murder, Insecure and I May Destroy You all feature female leads with layered characters.

Channel 4’s Banana Cucumber shatters stereotypes of the repressive, conservative British Caribbean parents and features an openly black gay cast. However, in the UK, there are few roles today in which ethnic minority talent play off screen and on screen – where race and ethnicity is not a centre focus. While stories like Sitting in Limbo, a factual drama by the BBC tells the story of Anthony Bryan, who was wrongly detained and almost deported by the UK Government, are much needed to educate and inform the wider society about the Windrush scandal, what’s lacking are the stories that feature ethnic minority talent as characters outside of the usual tropes and stereotypes or in storylines not centred on race and social inequality.

British talent like Homeland’s David Harewood said he struggled as a black man to get acting jobs in the UK because of racism in the country’s film industry. He is not alone in seeking jobs in the US and although the US is by no means exempt from racism, they are generally seen as more inclusive and audiences and talent turn to these shows because they feature people like themselves in normal roles.

What is evident is a desire for and the growing visibility of, British black artists, writers, presenters and talent who are re- enforcing a sense of confidence and self- assuredness about the culture and politics on the world stage resulting in a more self-assured black British identity globally. Nurturing talent and including them in the process is as important as seeing representative faces on screen.

As such, actors are questioning the roles they take – Viola Davis regrets her role in The Help as she felt that it wasn’t the voices of the maids that were heard but rather a centralisation on the white female characters who ‘do good’.

Other actors like Babirye Bukilwa are also speaking up on the issue.

Black Is The New Black featured successful black people so it is always good to see positive portrayals and inspirational figures. The Real McCoy - just good to see a predominately ‘minority’ cast of British comedians given a platform to create and be on television for several years. Trailblazers!

“I live my life from the perspective of ‘I must be part of the solution and not the problem’.”

Not only is this needed but Ofcoms’s study showed there was a desire among black African and black Caribbean people to see more positive examples of people from the same background on screen, to counter the negative stereotypes they often see.

Programmes which offered positive images of people from black ethnic backgrounds seemed to stand out in people’s minds, helping to explain the durability and fondness of people’s memories of shows like Desmond’s (Channel 4) and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

The black Caribbean population is showing the least growth and is made up of 0.6m and 1.1% of England and Wales total population.

Life in the UK today

The [windrush] debacle was a stark reminder that whilst we were born here and have created a life for ourselves here, to some we are still not considered ‘British.’

The Windrush scandal in April 2018 had devastating impact on people’s lives. People were detained, some lost jobs and homes, people were denied healthcare access and in some instances died due to the stress it caused-including Paulette Wilson, a prominent Windrush campaigner.

“She was like a gem, a precious gem, who got broken by the government.”

The incident reinforces the prominent and inhumane treatment that black Caribbean and other black citizens have faced and still face today in the UK, whether violent or in the form of systemic discrimination.

“In tabloids, the young lad (black lad) at Chelsea who bought himself and his mom a house was labelled as a kid who shows off and spends his cash on rubbish. The lad (white) at West Ham who did the same thing and the papers labelled him a good lad who cares for his family.” - Male, 18-34, C2DE, Mixed Race White, Black Caribbean, Birmingham [2020]

Young black Caribbean pupils, in particular boys, are more likely to be excluded from school. Systemic racism in education can manifest in many ways, including teachers’ low expectations, lack of diversity in the workforce, cultural clashes and stereotyping, which in turn plays out in all facets of life propelling a viscous cycle of social inequality.

2017-2018 figures revealed that black people were 3.8 times as likely to be arrested as white British people with 31 arrests for every 1,000 black Caribbean people (the highest out of all ethnic groups).

In May 2020 the murder of George Floyd sparked solidarity protests across the world, in particular in Western Europe, where many countries are still grappling with their colonial legacies and the systemic inequities minorities face with police brutality being just one facet of everyday life.

The protests also revived anger over other deaths of young black men such as Mark Duggan, a 29 year old black man killed by police in 2011 that set off riots in the United Kingdom.

Despite the fact that discrimination still blights lives, we exult in black Britons ongoing success and continuous contribution in the media, sports, music, fashion and the NHS. Trinidad-born Sir Trevor McDonald is one of the nation’s best-known journalists. Joan Armatrading from St Kitts was the first female UK artist to be nominated for a Grammy in the Blues category, and went on to receive a further three nominations. Jamaican born Tessa Sanderson was the first British black woman to win an Olympic gold medal (in 1984).

Discover more

Code of Practice Progress Report 2024/25

An update of progress on the BBC Creative Diversity Commitment

Elevate

Supporting deaf, disabled and neurodivergent talent in the TV industry.

Reflecting our world

Inspiring organisations around the globe to create content that fairly represents our society.