African influence within British society is undeniable.

Introduction

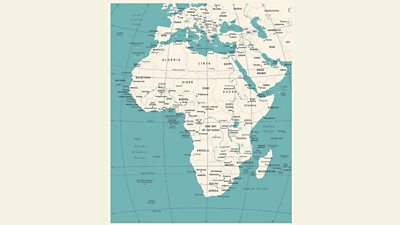

Note: Africa is a continent made up of 54 independent countries and the term ‘African’ denies the cultural differences between these countries. Depending on which country you are from you might relate to different parts of the world i.e. those from Egypt and Somalia are more likely to feel ties to Arabic cultures than Sub-Saharan Africa. Africa also has the greatest amount of variability in skin colour. To identify a whole country as ‘black’ African does not recognise all those who are African but from white European or Asian descent.

Research often broadly labels populations as ‘black African’ and we should be mindful of this in context of the above. For the purpose of this report, (and because limitations in data make it impossible to do otherwise), we are focused specifically on the ‘black African’ population in the UK as categorised by the UK Census.

The black African population is the fastest growing and largest black group in the UK. With the prominence of writers and programmes such as Michaela Coel’s I May Destroy You, the growth of the Afrobeats genre, and British-African stars in mainstream film and music promoting positive media portrayal (Daniel Kaluuya, Clara Amfo, Little Simz, Oti Mabuse and Stormzy), younger generations are starting to connect with their heritage and, through new and existing media platforms, represent and vocalise what it means to be British and African.

Read on to find out more about this incredibly diverse community. and its history.

Africa is the very root of human civilisation as we know it. Humans have lived in Africa far longer than anywhere else: our remote ancestors originated there some 7 million years ago.

History

“So far the evidence that we have in the world points to Africa as the ‘Cradle of Humankind.” - George Abungu, Director-General of the National Museums of Kenya

With so much time, Africa’s population has woven a complex, fascinating story of human interaction. Societies ranged from centralized government states, to village communities, to nomadic hunter-gatherer societies.

Major kingdoms and empires have existed across Africa for centuries e.g. Ancient Ghana in the 700s and the Mali Empire in the 1200s.

It’s only in the last fifty years that we have begun to scratch the surface of Africa’s rightful place in world history. Kemet (or Ancient Egypt) for example, is one of the most notable early African civilizations.

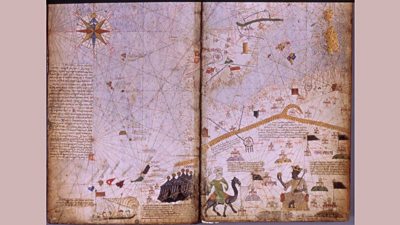

Mansa Musa, who ruled the Mali Empire in the early 14th century was known as the richest person of his time, and is also widely believed to have been the richest in history. The Mali Empire mined gold which, by the end of the 1200s, was the source of approximately 50% of the Old World’s gold supply. It was the wealth of West Africa and its natural resources, that encouraged the interest of European explorers.

Genetic studies have shown that humans migrated out of Africa about 60,000 years ago as the climate shifted from wet to dry. In terms of African immigration to the UK, the lack of accurate Census data means it has been difficult to provide clarity on the African population and its history in Britain.

However, there is evidence showing it stretches as far back as Roman times and further evidence is also recorded in Tudor England. But that doesn’t mean the African population may not have existed in Britain before that. As recent as 1966, the terms Old, New, and African Commonwealth were used to identify the size of the white/non- white populations in the United Kingdom making nuanced distinctions impossible.

Britain was responsible for large numbers of Africans taken to the Americas during the Atlantic slave trade. Between the 16th and 19th century, Britain along with Portugal accounted for approximately 70% of all Africans transported to the Americas. This crossing of the Atlantic was known as ‘The Middle Passage’, and an estimated 15% of Africans died at sea.

After slavery was abolished in 1833, Europe’s influence over Africa didn’t end. The African continent was still largely unexplored by the late 1880s, but less than thirty years later, only Liberia and Ethiopia remained unconquered by the Europeans. The rest-10 million square miles had been carved up by European powers (including Germany, France, Great Britain, Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, and Spain) in the name of ‘Commerce, Christianity, Civilization and Conquest’. This period was known as the ‘Scramble for Africa’ or the ‘Partition of Africa.’

Countries staked claims to any land they physically occupied and, boosted by superior military technology, European control was taken at the expense of local kingdoms and empires. In many cases land was stolen and redistributed to European settlers and Africans were subject to taxes. For the indigenous population, without money, many worked in fields and mines as a form a forced labour.

We were not happy being in that war. They were treating us as slaves. We were there not because we wanted to be there. But we were forced to go there.

When the British Empire was at its height during the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign (1876) until the end of the Second World War, people from occupied countries (Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon and the Ivory Coast) became British subjects and were able to enter Britain freely, settling in London and other urban areas (Bristol, Cardiff and Liverpool).

They worked in the NHS or other public sector roles but despite their contribution to British society, many faced discrimination from companies refusing to employ black workers. Please also see the black Caribbean chapter for more on racial discrimination during this time. Some Africans came to London as visitors and others stayed permanently, with recorded migration around 5,000 a year until the late 1980s. Many of today’s Londoners can trace their ancestry back to African countries.

“At the turn of the century, West Indians still made up the majority of the UK’s black population. But, as the 2011 census revealed, between 2001 and 2011, the British African population doubled, through both migration and natural increase. For the first time, probably, since the age of the Atlantic slave trade, the majority of black Britons or their parents have come to this country directly from Africa (West Africa, English Speaking former colonies), rather than from somewhere in the Americas.” - David Adetayo Olusoga Obe, British Historian, Writer, Broadcaster, Presenter And Film-Maker.

There is little acknowledgement and awareness of the 600,000 Africans that served in the British forces during World War II. These African soldiers were press-ganged by the British army and stationed in battlefields far from home.

Britain would go on to pay these soldiers an end-of-war bonus according to their rank, length of service and ethnicity, meaning black troops received just a third of the pay of their white counterparts.

One Kenyan veteran, Gershon Fundi, now 93, was not among Britain’s willing recruits; he was effectively tricked into wartime service.

Britain’s violent conscription of African soldiers has recently come to light. Many soldiers were mistreated, taking beatings by their superiors and public floggings. Such revelations, which recently featured in a documentary for Al Jazeera English, have triggered calls for the government to make an official apology and pay compensation to the last surviving veterans.

In 2019, a government spokesperson refused to comment specifically on any of the allegations, “The U.K. is indebted to all those servicemen and women from Africa who volunteered to serve with Britain during the Second World War. Their bravery and sacrifice significantly contributed to the freedoms that we all enjoy today.”

All too often, the stereotypical images people hold of black Africans today, are greatly influenced by the legacy of colonialism:

“People don’t realise just how much of an impact the interaction with Europe has had on Africa… You come to a society, extracting all you can, destroying the fabrics that existed before and taking what you can take…All we get now [in the media] is ‘these people [Africans] they been killing each other, it’s how they behave, they are just savages’ not acknowledging if you [Europe, among others] hadn’t elevated certain members of society, and fragmented traditional systems of government, they might not have the situation they have right now.” - Uzodinma Iweala, American-Nigerian Author, Beasts of No Nation

The closely tied history of Africa and Britain is still being unearthed today. Crucially, the curriculum taught in schools to further develop our understanding of African life in Britain is being reviewed, but there is still work to be done to expose other aspects of African life in Britain.

The majority of African migration occurred decades later, and they tended to be more middle-class migrants, more akin to the ideals of university education.

“We have existed in Britain and been pioneers,inventors, icons. And then colonialism happened, and that has shaped the experiences of black people - but that is not all we are.”

Lavinya Stennett, Writer, Artist And African Studies Student And Founder Of The Black Curriculum.

Since the turn of the century the black African community living in Britain has more than doubled, becoming one of the largest, and youngest, minorities currently in the UK. Migration for work-related reasons now greatly exceeds asylum migration and the economic circumstances of the African population is relatively favourable.

“There was a large wave of migrants who came to Britain in the 1940s and 1950s from the Caribbean and they tended to find work in blue-collar positions, in factories and on building sites…On the other hand, the majority of African migration occurred decades later, and they tended to be more middle-class migrants, more akin to the ideals of university education.”

Heidi Mirza, Professor Of Race, Faith And Culture At Goldsmiths College, University Of London

However, it was reported that The Home Office’s hostile handling of visiting African professionals over the past two decades (on the assumption that most Africans are fleeing) is still affecting academics in particular today.

You have to understand that Africa is a continent not a community – we’re all so different.

Culture

In a recent study by Foresight Factory on defining factors of identity, 50-60% of British black African/Caribbean respondents, agreed that ethnicity played a key role, the largest of any group.

The singular viewpoint of ‘black’ as an ‘identifier’ or an ‘ethnicity’ not only denies cultural differences between the population, it also denies the nuance within a vastly diverse community.

For example, Nigeria alone has more than 250 ethnic groups/tribes, with their own traditions and customs, and over 500 languages. The acknowledgement of different cultures and histories (shared and separate) is described by Linda Bellos who has been advocating for the use of ‘African’ to refer to people of African heritage, since ‘black’ speaks only of skin colour; not history.

“Black remains a political term that we should be encouraging, if it means being united by a common experience of racism and commitment to fighting that racism. The term black has a proud heritage, one we should wear with honour and pride. But if black now means Caribbean or African, I reject it entirely. I am insulted and slighted by it, since it means, in the context of “black and Asian” that I come from no place.” - Linda Bellos, British businesswoman, radical feminist and gay-rights activist

When we attempt to define African culture and identity, we have to be mindful that we are viewing a broad ethnicity comprising different sub communities that are resistant to having their heritage and culture boxed in simplistic labels.

RELIGION

Religion plays a key role in the value of community, especially for first generation family members and those experiencing barriers towards participating in mainstream culture. Places of worship and religious communities are recognised as trusted and respected sources of information where people can gather news, often tailored to their specific background and cultural needs. As commented on by David Olusoga: “Many non-white people felt that while it was possible to be in Britain it was much harder to be of Britain. They felt marked out and unwanted whenever they left the confines of family or community.”

Christianity is the largest religion for African communities living in Britain, growing by 1.2% between the 2001 and 2011 census. Around 93% of sub- Saharan Africans are either Christian (63%) or Muslim (30%), making the continent one of the most religious in the world. The historical impact of the spread of Christianity in Africa is just as evident through Nigerian-born residents in the UK, labelled as the second largest Christian group (95,000) behind those from Poland (464,000).

We have existed in Britain and been pioneers, inventors, icons. And then colonialism happened, and that has shaped the experiences of black people - but that is not all we are.

FAMILY

Evident in black African communities is the value and strength of the family household and strong family values.

In the most recent Census, black Africans identified as the largest black community with households comprised of Married with Dependent children (20.3%), or Lone parent with Dependent children (20.2%). Families within this community were likely to either be living with their families or close by. Extended families also typically live in short distances from other family members and the tradition of multiple generations living together was evidently strong.

“There is a lovely African proverb: ‘It takes a village to raise a child.’ African culture recognises that parenting is a shared responsibility - acommunal affair - not just the concern of parents or grandparents, but of the extended family. Uncles, aunts, cousins, neighbours and friends can all be involved and all have a part to play.”

The close-knit relationship between African family members demonstrates the value grandparents bring to family life, and the role grandparents play in how families manage their caring and financial needs. Grandparental childcare is widely used to enable parents to work while providing childcare for grandchildren.

Marriage is traditionally also a very important union with younger generations today encouraged to marry and ‘settle down’ by more traditional and conservative parents. While we cannot generalise for every African culture, Nigerian culture, as an example, promotes the values of marriage, celebrating the tradition with expensive and elaborate weddings involving the community and multiple family members. While younger generations look towards their heritage when celebrating their identity, traditional family values such as these can be seen as a clash not just from a generational perspective but also a cultural perspective with those who have grown up in British society.

LANGUAGE

Nearly 30% of the world’s languages are spoken only in Africa.6 As of the 2011 Census, from the twenty largest non-English languages, Somali (native to Somalia) is the 14th largest language spoken in England and Wales. There are still a range of East and West African languages used by African families in Britain such as Amharic (Ethiopia), Tigrinya (Eritrea), and Nigerian languages like Yoruba and Igbo.

Those aged 35+ are the largest group using an African language as their main language, with this decreasing with younger generations suggesting that as younger generations grow up in British society, they are losing a sense of connection with their heritage and developing a language barrier between themselves and the older generations.

“I don’t have any plans to go back to Nigeria, but if I stay in this country I worry we’ll lose the language…If you don’t speak Yoruba, how are your children going to speak it? How are their children going to speak it’” - Gbemisola Isimi, creator of Culture Tree

This has led to the creation of initiatives focused on teaching children and second generation parents African languages. Culture Tree is one such example which aims to teach Yoruba to Nigerian families who want to learn more about their heritage.

FOOD

“If tikka masala, teriyaki, and dim sum can make their way into Britain’s culinary lexicon, then why not kenkey, fufu, suya, and chin chin?” Thanks to a growing West African diaspora and increased African visibility in mainstream culture, African cuisine is looking set to expand further into the British dining experience.

The influences are diverse and range from Ethiopian delicacies, traditional Kenyan Indian BBQs through to Moroccan recipes and West African dishes.

This has come about from younger generations yearning to understand and develop their heritage through learning traditional cuisines, their history, and pay homage to their parents and ancestors who cooked it first. Today, many of the newer West African food businesses and influencers reach people via social media and are the result of generations of unnoticed work from home cooks, restaurateurs, grocery stall owners, and pioneering entrepreneurs looking to develop the future of British West African food.

‘We cook West African and you know, we’re paying homage to how the grandmothers would cook first, but there are some modern techniques there, second.”

Aji Akokomi, British-Nigerian Restaurateur

FASHION

Throughout the continent, the national dress is a symbol of pride, reflecting the society as well as status. In some instances, traditional robes have been replaced or influenced by foreign cultures, like colonial impact or western popular dress code. There are many varied styles of dress and the type of cloth plays an integral role in fashioning the garment.

“Wearing African clothing is a wonderful way for many to celebrate our cultural heritage and to commemorate the beauty of our motherland. Any study of African clothing and fabrics must take into account that Africa 5 minutes ago, 50 years ago, 500 years ago and Africa 5000 years ago is not a static feature. A diverse Africa has influenced and been influenced. Concepts and cultures of African clothing have been exported and re- imported, just as genes, ideas and technologies have exited and re-entered African continents.”

A recent TikTok phenomenon started by Indian- American creator Milan Mathew, has shown younger generations celebrating traditional clothing. Her twist on the ‘hotseat’ trend was a transformation into her traditional Indian clothing. Since then, many others have followed suit flaunting their traditional Vietnamese, Nigerian, Georgian, Korean fashions, and more.

"I think it was me embracing my culture that made people want to actively and openly embrace theirs, too.”

Milan Mathew, TikTok Creator

EDUCATION

Feyisa Demie, Head of Research and Advisor for School Self-Evaluation at Lambeth Council found that black African parents and pupils place an extremely high value on education when it comes to furthering their available prospects. The importance of an education and strong grades is promoted by generational family traditions and inspirational role models in the community. British black African students results in A Levels have improved substantially according to Government statistics. This may also be explained by later immigrant African families being more akin to the ideals of university education.

ENTS AND FILM

With a growing interest in African film, music, food and fashion, black African creators and artists are more regularly celebrated for their contributions to the arts which in turn is helping younger black Africans living in the UK to explore and reconnect with their heritage.

In film, African history and black stories have been brought to the forefront of people’s media consumption. Hollywood films such as Black Panther have boosted worldwide interest in African film and television and expanded its exports to a broader audience. In 2019, French- Senegalese Mati Diop’s directorial debut, Atlantique competed for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and was the first film directed by a black women to feature at Cannes.

The Nollywood film industry is at the epicentre of Nigeria’s creative arts economy and now has the ability to globally compete in film production with the likes of Hollywood and Bollywood; in both quality and quantity. A factor in Nollywood’s progress in recent years has been the growth in streaming and video-on-demand services.

The problem of limited cinematic releases in Africa (due to lack of cinemas compared to the overall population) and worldwide has now been revolutionised as African productions can now be released as original content on VoD services straight to the consumer. Since Netflix launched in Africa in 2016 it has made significant investment in Nigerian film and TV productions with Lionheart (2018) being its first original Nollywood production.

Nollywood is now able to attract a broader audience outside of Africa and in the UK it is being celebrated amongst the younger generation who look towards it for a sense of identity and heritage. (See more on film and Nollywood in the ‘Shift in Portrayal’ section.)

MUSIC

In the music scene, Afrobeats has expanded into the mainstream with musicians like Burna Boy, Davido, WizKid, and Tiwa Savage, attracting thousands of fans on streaming sites and garnering record deals with Western labels.

Afrobeats artists have also collaborated with the likes of Drake, Stormzy, and Beyoncé, who last year created The Lion King: The Gift album featuring a host of African talent.

The BBC has also begun catering to the growing UK Afrobeats scene with the creation of the Radio 1Xtra official UK Afrobeats Chart and DJ Edu hosting Destination Africa promoting the hottest music of African origin.

Jamal Edwards set up SBTV, an online urban music channel, in 2006 because “mainstream media wasn’t supporting the artists I was listening to” but now this genre of British urban music is attracting much bigger audiences. He points to talent such as Rapman whose YouTube series, Shiro’s Story, led to a cinema release, Blue Story, which was backed by BBC Films and Viacom’s Paramount Pictures.

Jamal Edwards attests to the migration from traditional media: ‘It’s true that new technology has allowed many creators, including myself, to be less reliant on the traditional routes...”

For younger generations, digital media tools (Instagram, Netflix, Spotify etc.) that can provide a creative connection to their heritage and culture are sought out. They place a higher value on the importance of social media and YouTube as personalised creative platforms, accessible to all, where anyone can have a voice. These platforms are especially relevant for second and third generation black Africans who feel culturally-disconnected.

Media Portrayal

Due to the homogenisation of the ‘black’ identity, and the often lack of character development within film and television, representation in media often isn’t broken down by specific ethnicity. We’ve aimed to focus on black African representation and portrayal specifically where possible. We’d also encourage you to read the black Caribbean chapter too.

In a 2011 study by the BFI on minority portrayal in the UK film industry, when speaking to black African audiences they found people felt there was little authenticity regarding the individual’s true heritage; characters are simply ‘black’.

Legally Black, a young black activist group in Brixton expressed their frustration about the lack of black actors in films and TV shows by recreating famous movie posters, including Titanic, Harry Potter and The Inbetweeners, with black people taking the leading role.

There is a sentiment amongst black audiences that there is minimal content on offer across mainstream platforms that accurately represents their history and values. Some films are believed to paint stereotypical picture of multi- cultural youth and black people in particular.

In similar themes we’ve seen across the report, stereotypes are seen to enforce one narrow story.

In Ofcom’s Representation and Portrayal of Audiences on BBC Television 2018 Report, it was stated that some participants were less inclined to complain about shows that feature a black man as a drug dealer when it is felt there is a wide range of portrayal of black men on.

Many black African and black Caribbean participants also claimed there are very few black presenters on TV.

While this chapter predominately covers some stereotypes of black men, we have looked at the portrayal of black women, who are often seen as undesirable, in the black Caribbean chapter.

“This may be hard to believe, coming from a black man, but I’ve never stolen anything.” Paul Beatty, author of The Sellout

In Layla F Saad’s book, Me and White Supremacy: How to Recognise Your Privilege, Combat Racism and Change the World, she identifies examples of racist stereotypes sometimes associated with different groups. It is interesting to look at this list and see the stereotypes that have become prominent, in media content from TV and film to sport and music.

The UK film industry’s portrayal of black people is often seen as depressing, dark and violent – often referred to as ‘grime’ films and typecasting of black talent as gangsters and drug dealers. In a Humanities and Social Sciences Communications study looking at the segregated gun as an indicator of racism and representations in film, the authors state that the ‘symbolic meaning of guns in the hands of blacks is violent, exceptional or some other stereotypical character trope.’

“The other day I watched this documentary where they were saying how there was violence, how there were gangs, young black women as well as young black men and the way they were delivering it, it was so negative. And it was just a minority of these people, but they made it look as though it was across the board.”

Female 55+ Black Caribbean Nottingham

In a speech to MP’s by Idris Elba in 2016, he expressed his concern over the effect of negative stereotypes in the UK Film and TV industry, stating,

“I was busy, I was getting lots of work, but I realised I could only play so many ‘best friends’ or ‘gang leaders… I knew I wasn’t going to land a lead role. I knew there wasn’t enough imagination in the industry for me to be seen as a lead. In other words, if I wanted to star in a British drama like Luther, then I’d have to go to a country like America.”

In summary, when it comes to black males, the media leans towards individuals such as the drug-dealing criminal; dysfunctional families with absent fathers and struggling single mums; and the joker masking shortcomings. This can feel demoralizing and reduce the self-esteem and expectation of people looking towards the industry for role models. Even “positive” portrayal of black men often present variations of these tropes or present limited, often unrealistic, options (e.g. rap stars or NBA players).

Afua Hirsch, author of Brit(ish): On Race, Identity and Belonging, claims mainstream films and TV have become the setting for the role of black characters to be saved by the white hero. For example, films involve white women rescuing tough, inner city kids. ‘Save a thug’ was the coined theme from these films.

If it wasn’t about a white saviour rescuing a black victim, then a white man is being assisted by a ‘Magical Negro.’ The ‘Magical Negro’ is imbued with ‘deep spiritual wisdom’ and sometimes even supernatural powers, but they never act as ‘the hero’ because their sole purpose is to help the white lead become a better person/ leader/warrior.

In a lecture to Yale University students, Director Spike Lee criticised the trope as used within The Legend of Bagger Vance,

“Blacks are getting lynched left and right, and [Bagger Vance is] more concerned about improving Matt Damon’s golf swing!”

American journalist and historian, Richard Brookhiser argues that America has long loved the idea of the ‘numinous negro’- black politicians, preachers and movie characters that lift up the spirits of white audiences. He points out that black people are only allowed to be at either extreme- criminal or saint. They cannot be complex and flawed human beings, either in fiction or in public life.

“I see that the magical negro trope is an outcome of the white privilege of storytellers. This term reflects how societies that are dominated by white cultures come to normalise white experiences to the point where people from the dominant group do not immediately recognise how racial relations are set up to benefit them. Even when it is well-meaning, even when it does not comes from the conscious desire to denigrate minorities, the magical negro and its variations reproduce unequal power relations between white and people of colour.’ Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu, American Nigerian Writer

A recent report from RunRepeat on bias found that athletes with darker skin tone were significantly more likely to be reduced to their physical characteristics or athletic abilities, namely pace and power, while white athletes were more likely to be described for their intelligence and their hard-working aptitude during the game. The report highlights the role commentators play in shaping the perception of an athlete - it is important to consider the far- reaching consequences of these perceptions.

“Till this day, Pogba and Yaya Touré are described as big, strong and having raw power and pace. You’d hardly hear about the clearest features of their game, supreme technique, boundlessskill and visionary passing. ‘Look at that pace, he’s so powerful’.” - Tweet

A telling example is the treatment of Serena Williams by journalists and commentators of tennis tournaments such as Wimbledon, the U.S Open, and the Masters. Afua Hirsch observes that, while white tennis stars, such as Maria Sharapova, were praised for their graceful playstyle, Serena was described as using ‘brute force’ and ‘intimidating her opponents’. Serena Williams ‘runs women’s tennis like Kim Jong-Un runs North Korea – ruthlessly’ said one influential magazine.

A Shift in Media Portrayal

We are slowly beginning to see a positive change in representation regarding black communities and the black British-African population. This is partly made possible by the digital landscape that is breaking down geographical barriers that once kept audiences from accessing content made by African talent. Changes in technology have begun to level the global playing field, giving black voices a platform and making their content easily discoverable.

Now streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music, as well as Netflix and IROKOTV, host Nollywood films. In 2020, as a result of the popularity and variety of Nollywood content, Netflix released its first African made show Queen Sono which, on its week of launch in late February, was the seventh most watched show in the United States, Netflix’s biggest market.

‘I’ve often said that Africa, as a continent, we’ve remained so quiet. We’ve been so quiet, and our stories have just never been told. Now we’re talking about Black Lives Matter, and black stories matter. And a lot of the broadcasters are saying that it’s time now for there to be more black stories on screen and more black creatives involved in the process. But I’m happy to say that, you know, we started our journey with Netflix before then.’ - Nigerian Producer Mosunmola Abudu, Creator Of Ebonylife Films

For Netflix, the creation of their sub-brand Strong Black Lead (SBL) has amplified content specifically targeted to various slices of the black experience. Since its premiere, the brand has worked to establish SBL as an integral part of Netflix through editorial content and original programming created exclusively for the brand.

They’ve launched successful initiatives including the #HeyQueen short-form video series featuring celebrated black women, #BetweenTwoFaves which highlights conversations among icons across the black diaspora in entertainment, and the Strong Black Legends podcast and video series where stars of classic black movies are interviewed.

Beyond digital platforms’ support for black talent, storylines across mainstream TV and film are also improving and reflecting more authentic and real experiences. In recent years we have seen such films as Moonlight, I Am Not Your Negro, and Kiki (the follow-up to Paris is Burning) push into mainstream viewing and shine a light on stigmatised views towards the LGBTQ+ community. Social activist and writer, Phil Samba details: “I’m 28 now, and growing up, I didn’t know anyone who was gay, nor were there any black gay role models on TV or in the media. It was like we didn’t exist.”

A report by the ONS stated of the total UK black African population only 0.9% describe themselves as openly gay. On TV, black LGBTQ+ representation is pushing forward much faster than mainstream cinema. Sex Education, featuring Scottish-Rwandan born Ncuti Gadwa portraying Eric Effiong, is a character praised for not being relegated to the cliché of the gay or black best friend/sidekick stock character. Dear White People, Pose, and Sex Education all provide authentic and diverse role models to younger generations.

The US TV and film industry is considered to provide more positive portrayals of black characters. The Spanish Princess is a period drama set in Tudor England which cast Stephanie Levi- John as Catalina “Lina” de Cordonnes, whose character is based on an African Iberian lady-in- waiting who served in Catherine of Aragon’s court for over 20 years.

Black Panther, Marvel’s 2018 blockbuster all-black superhero story and cast marked a milestone in representation for the black African community globally. The film sparked a worldwide celebration of African culture, with the character’s famous “Wakanda Forever” salute giving millions an added sense of pride in their African heritage.

On display at the premiere were head wraps made of various African fabrics and Oscar winner Lupita Nyong’o wore her natural hair tightly wrapped above a resplendent bejeweled purple gown. Men, including star Chadwick Boseman and Coogler, wore Afrocentric patterns and clothing, dashikis and boubous. Co-star Daniel Kaluuya, arrived wearing a kanzu, the formal tunic of his Ugandan ancestry.

“The celebration of African culture went beyond the screen to the premiere for which the invitation read “royal attire requested.” Science fiction has long been criticised for its lack of racial diversity and inclusion. Black Panther has combatted the lack of blackness in depictions of the future and has since become a major commercial and mainstream contribution to Afrofuturism – a philosophy described as the reimagining of a future filled with arts, science and technology seen through a black lens.

“Afrofuturism is me, us... is black people seeing ourselves in the future.” - Janelle Monáe, Singer-Songwriter, Rapper, Actress, And Record Producer.

In 2019, British-born Yoruba writer Tade Thompson became only the second writer of black African heritage to win the Arthur C Clarke award for science fiction with his novel Rosewater; set in Nigeria 2066.

In the wake of the success of Black Panther, and the success of writers like Thompson and Okorafor, Geoff Ryman says ‘almost every publisher now wants to be able to say they are open to speculative fiction by Africans’.

Moulded and built on the foundation of reggae, dancehall and sound-system culture, grime grew from the cross-collaboration of African and Caribbean diaspora. Grime is one of the spaces where Africans and Caribbean people were coming together.

Life in the UK today

The black African population is the fastest growing and largest, black group in England and Wales, making up 1.8% of the total population at a size of 1.3 million.

Geographically, the 2011 England and Wales Census showed that 58% of the black African population resides in London with smaller populations in the East (7.1%), South East (8.8%) and West Midlands (6.5%). While Scotland doesn’t categorise its population by ‘black African’ specifically, the 2011 Census showed that African, Caribbean or black groups made up 1% (about 36,000) of the population of Scotland, an increase of 28,000 people since 2001.

Recent census data shows the black African population in England and Wales is largely made up of younger generations with 36% of the population aged 15-34. Principally as a result of migration and the children of earlier migrant generations reaching adulthood.

Black African (32.3%), black Other (31.6%), and black Caribbean (29.2%) people were the most likely to live in the neighbourhoods most deprived in relation to housing and services in England. However, things are progressing. Black African students, alongside Chinese, Indian, Irish and Bangladeshi are now outperforming their white British peers in obtaining five or more GCSEs at grade A* to C.

There have been successful African entrepreneurs in Britain going back 200 years. A recent example is Ghanaian-born (though of Trinidadian parentage), Margaret Busby OBE. She co-founded independent book publisher Allison & Busby and was Editorial Director for 20 years, before it was sold to major publisher WH Allen in 1987. She is now an award- winning writer, editor and lecturer, and sits as a judge for many literary awards.

Although historically the homogenisation of African and Caribbean communities into a singular identity of ‘black’ resulted in “two equally marginalised and oppressed black communities pitted against each other [when it came to accessing resources] due to the laziness of the state”, today for second and third generation communities especially, the African/Caribbean relationship is much more focussed on embracing commonalities, identity and black history.

This has had beneficial implications for modern black British history and the shaping of ‘black culture’ and identity today – evident in language and music which is increasingly becoming a fusion of Africa and the Caribbean. These traditions are being kept alive and strengthens the bonds between black Brits.

Discover more

Code of Practice Progress Report 2024/25

An update of progress on the BBC Creative Diversity Commitment

Elevate

Supporting deaf, disabled and neurodivergent talent in the TV industry.

Reflecting our world

Inspiring organisations around the globe to create content that fairly represents our society.