Public Health reform - 1848-1859

A report by Edwin Chadwick led to the 1848 Public Health Act. Although limited in its scope, this was an important milestone in public health. In 1858, the Great StinkA period of hot weather that exacerbated the smell of raw sewage and industrial pollution in the River Thames. forced the government build a new sewer system in London.

Edwin Chadwick’s report

Edwin Chadwick worked for the government’s Poor Law Commission. He was given the task of investigating the causes of poverty and advising on how to deal with it. Between 1839 and 1842, Chadwick examined detailed statistics about death and disease. He worked with a wide range of officials, including doctors.

Chadwick published his Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Britain in 1842. It contained details about living conditions and public health that shocked the population. It said that:

- a nationwide public health authority should be set up

- local areas should be forced to provide clean water and new sewerage systems

- new technology, such as egg-shaped sewers, should be used

- rates A payment made by householders to their local council. should be increased to cover the expense

Opposition and support

Chadwick’s proposals were controversial. Many people disagreed with his recommendations.

| Group | Reasons for opposition |

| Property owners | These were the middle-class (and better-off working-class) rate payers, who objected to paying more taxes. |

| Water companies | They already made big profits from supplying water to middle-class districts. If they had to extend their supply, they would need to invest huge sums of money on infrastructure, possibly for not much gain. |

| Some ordinary people | Many people supported laissez-faire on principle and didn’t believe it was the government’s job to interfere at this level. |

| Group | Property owners |

|---|---|

| Reasons for opposition | These were the middle-class (and better-off working-class) rate payers, who objected to paying more taxes. |

| Group | Water companies |

|---|---|

| Reasons for opposition | They already made big profits from supplying water to middle-class districts. If they had to extend their supply, they would need to invest huge sums of money on infrastructure, possibly for not much gain. |

| Group | Some ordinary people |

|---|---|

| Reasons for opposition | Many people supported laissez-faire on principle and didn’t believe it was the government’s job to interfere at this level. |

However, many leading politicians and other organisations supported change. The Health of Towns Association was set up in 1844 and pressure mounted on the government. Parliament passed the first Public Health Act in 1848.

The 1848 Public Health Act

The 1848 Public Health Act was limited because most of it was permissiveSomething that is optional. This meant that it allowed but did not force local authorities to take action.

- The act set up the General Board of Health.

- It allowed areas to set up a local board of health and increase the rates. However, there had to be support from 10 per cent of rate payers.

- It forced towns to set up a board of health where the death rate was high.

- If set up, the act allowed boards of health to take command of all sewers. It also gave boards the power to supply water if a private company would not. Boards also had responsibility for cleaning the streets.

The act had a limited impact. By 1853, only 163 places had set up a board of health.

The Great Stink, 1858

During the hot summer of 1858, water levels in the River Thames fell so much that the smell of sewage became unbearable. It was impossible for MPsMembers of Parliament. in Parliament to continue with their debates. They decided to take action.

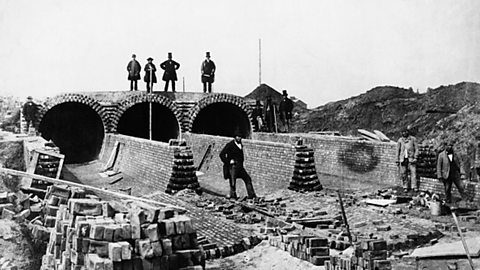

Joseph Bazalgette’s sewers

The government appointed Joseph Bazalgette as the chief engineer of a huge sewer-building project. The planning began in 1859 and the main part of the work was completed in 1865. London’s sewers were revolutionised:

- 1,300 miles of new brick sewers were laid.

- Pumping stations took waste eastwards, where it was dumped far downstream of the city.

- London had far fewer deaths during the next cholera epidemic (1865-1866).

- Bazalgette’s sewers are still in use today.