Causes of the 19th-century public health crisis

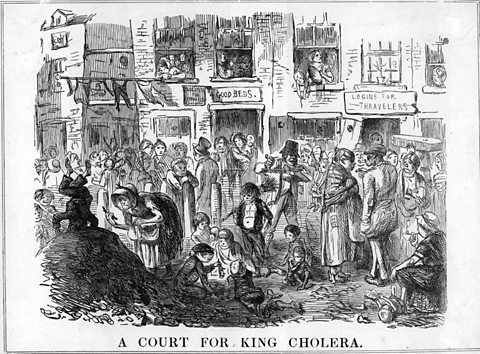

Britain’s towns and cities experienced a public healthThe health of the population as a whole, and methods used to prevent disease and keep people healthy. crisis in the first half of the 19th century. In poorer areas, there was a lack of clean water, poorly built and overcrowded housing, and no proper sewers. Deadly diseases such as tuberculosisA bacterial infection (also known as TB) spread through breathing in tiny droplets from the coughs or sneezes of an infected person. and typhusA bacterial disease usually passed from rats, cats, etc. to humans via lice, fleas and ticks. It spreads in areas of poor sanitation and through close contact between people. Possible complications include loss of hearing, organ damage and gangrene. were common. There were outbreaks of choleraA bacterial infection caused by contaminated drinking water. in 1831 and 1848, and thousands of people were killed.

There were three main reasons for the public health crisis:

- the rapid pace of industrialisation

- weak local and national government

- lack of understanding of the causes of disease

The rapid pace of industrialisation and the impact of population growth

Towns and cities experienced unprecedented growth from the late 18th century onwards. In 1750, Manchester had a population of around 18,000 people. This had increased to 90,000 by 1800. Just 50 years later, in 1850, there were 400,000 people living there. The pattern was similar in other industrial cities, such as Birmingham, Glasgow, Liverpool and London.

The rate of growth meant that demand for houses far exceeded supply. Houses were built quickly and cheaply. The government did not have strict building regulations, so landlords made big profits by building new houses close together. They often used poor-quality materials and unsafe foundations.

The fast pace of growth also meant that town infrastructures and facilities - such as water supplies and systems of sewage disposal - simply could not cope with the pressure of the growing population.

These conditions helped to spread many deadly diseases.

Weak local and national government

Two factors laissez-faireTranslated as ‘leave well alone’ or ‘let the people choose’. A government policy of interfering as little as possible in social and economic policy. attitudes and the reluctance of richer people to pay higher rates meant that it was rare for local or national governments to get involved in public health issues.

| Factor | Description |

| Laissez-faire | This was the dominant attitude of the time. People did not expect the government to ‘interfere’ in things like building regulations, wages or improving living conditions. This wasn’t just about money - people expected the government to give businesses and individuals freedom and stay out of their lives as much as possible. There was a strong belief that people should help themselves to live better lives and not rely on others. |

| Rich people's reluctance to pay higher rates | At a local level, town councils and authorities were run by richer, middle-class people whose living conditions were much more pleasant and spacious than the working-class districts. They paid rates, which were spent on the upkeep of the local area. Many of these people were not in favour of having their rates increased in order to provide better facilities for the poor, such as sewers. This was partly because many of them were fairly ignorant of how bad living conditions were in the slums. |

| Factor | Laissez-faire |

|---|---|

| Description | This was the dominant attitude of the time. People did not expect the government to ‘interfere’ in things like building regulations, wages or improving living conditions. This wasn’t just about money - people expected the government to give businesses and individuals freedom and stay out of their lives as much as possible. There was a strong belief that people should help themselves to live better lives and not rely on others. |

| Factor | Rich people's reluctance to pay higher rates |

|---|---|

| Description | At a local level, town councils and authorities were run by richer, middle-class people whose living conditions were much more pleasant and spacious than the working-class districts. They paid rates, which were spent on the upkeep of the local area. Many of these people were not in favour of having their rates increased in order to provide better facilities for the poor, such as sewers. This was partly because many of them were fairly ignorant of how bad living conditions were in the slums. |

Lack of understanding of the causes of disease

It wasn’t until the 1850s that some people began to directly connect disease to unclean water. Even then, these ideas were not proved correct until Louis Pasteur’s germ theoryLouis Pasteur published this theory in 1861 to prove that bacteria caused disease. The theory was widely accepted by the 1880s. was published in 1861.

For the first half of the 19th century, the most popular view about how disease was spread was still the miasma theory. This was the belief that disease was caused by breathing in the bad air created by decaying rubbish and human waste.

This meant that when there were epidemics (eg the cholera epidemic of 1831-1832), the authorities did not take actions that would have helped.