BBC Pop Up’s US road trip: In search of the stories people really want told

Matt Danzico

is head of the BBC’s Video Innovation Lab. Twitter: @mattdanzico

In part two of his blog, Matt Danzico reports on specific challenges and lessons for the small team behind a mission to find new stories and new ways to tell them:

In terms of output, the aim of BBC Pop Up was to produce feature videos about issues in each community we visited. These ran on the website, social media and BBC World television as they were created.

The online version of each story would often be five to seven minutes in length; the television version was often precisely three minutes; and the social media cut was one minute (which we used as a trailer on social to drive traffic to our full story).

We’d also create shorts about interesting cultural issues. At the end of each month we’d edit our content into a half-hour TV-only compilation for BBC World - other videos being posted and aired on appropriate platforms.

Social media

We held Tumblr, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts throughout the six-month project. But with all the video work Benjamin Zand and I were doing we struggled to engage on the level we wanted to throughout the trip.

Our social media presence sky-rocketed during month five, due to Lindsay Patross (above) whom I’d interviewed while doing a story in Pennsylvania. She was a local blogger who’d amassed a following in Pittsburgh that rivalled local newspapers and it seemed obvious that she needed to become part of the Pop Up crew.

Lindsay acted as our community engagement producer. Her role was to tap the existing local online networks in the various communities and attempt to use their reach to get our material to local audiences through retweets and blog posts.

She posted material on our social media accounts as well as generating some of her own. But more importantly she befriended local bloggers, journalists and start-ups.

In each of our destinations, across 19 states, Lindsay hit the ground running to develop friendships with those with strong digital voices as a way to get the area chatting about our visit. Nearly each day she met over coffee with a new blogger or journalist to discuss how our work might overlap with theirs.

Lindsay also found the nooks and crannies of the internet and embedded our content there. From Trip Advisor forums discussing haunted houses to local subreddits, she attempted to tap any online cluster she thought might be interested in our content.

A reminder of where we started

As previously mentioned, Benjamin and I both worked in the BBC Video Innovation Lab (VIL) prior to the launch of Pop Up. VIL was a London-based group that was brought together for one year to quickly create new programming aimed at thinking about new ways of engaging audiences online.

The lab is responsible for much of the new digital-first programming being developed by the BBC. It’s behind BBC Trending’s video offering, BBC Shorts on Instagram, text-based explainers, the BBC Reddit channel, and others.

The World Wide Web is playing less and less of a role in modern-day internet use. So the idea behind all of these new BBC creations was to produce content designed for places like mobile chat applications or social media platforms - new spaces people inhabit online.

In the same way, we conceived BBC Pop Up because we wanted to branch out and away from the existing BBC bureaux and cities where the BBC often reports.

Wins and failures

We received around 10 press mentions in each region we visited, from local NPR interviews to write-ups in the local newspaper. The fact that the BBC was in town seemed to be enough to generate some press around the project.

Our reporting was discussed during city council meetings in Colorado and a ‘state of the city’ address in Washington. The mobile bureau was also featured in national and international media - all helping to bring eyeballs to our content.

Though some of the videos often received an inflated number of views, the view count wasn’t as consistent as we would have hoped. We found videos that touched on a sense of identity within a community were ones that did well on the website.

For instance, the video about accents in Pennsylvania and the one about life in one of the most dangerous neighbourhoods in Louisiana (pictured top) trended on the BBC website for an entire week, while others dropped off the most-watched list quickly.

To me, this tells us that Niemen Lab’s 2013 article about the way BuzzFeed capitalises on emotion and identity continues to ring true, even for the BBC. Some of our more emotional videos continued trending for a week, even once we took them off the homepage.

Though we’re still crunching the data, it appears as if this phenomenon is the result of micro-targeting a demographic and getting the video to trend within social communities online. That certainly seemed to be the case with the Pittsburgh accent piece. I wish we could have seen the same number of views for the story we did on pollution in Pittsburgh. But I think this has a great deal to do with how the story was constructed rather than the subject matter.

Lessons learned

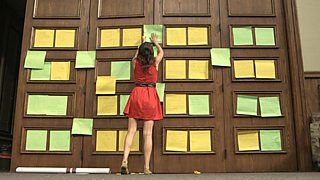

We collected nearly 30 story suggestions in each town we visited (as above, at a community meeting in Baton Rouge, Louisiana). Again and again, two story ideas that were suggested to us were the revitalisation of downtowns across America and the challenges Native American populations are facing.

In South Dakota, Arizona and Washington State, Native American-related stories were often the ones people mentioned first. Benjamin did a fantastic story (pictured below) on youth on the Pine Ridge Reservation, but we could have done many more throughout the trip.

Yet throughout our 15,000-mile journey there was a larger recurring theme - one I never anticipated.

We as journalists sometimes misrepresent the communities we visit with our stories. For instance, during our first stop in Colorado our editors and viewers asked us how we would cover the recent legalisation of marijuana. To our surprise none of the locals we spoke to even suggested the story. When asked Coloradans said marijuana was a "non-issue".

In Tucson, Arizona, we expected to be asked by locals to do a story on losing jobs to illegal immigrants coming across the nearby border. But no-one ever suggested it. Mexican culture was a “strong and proud part of the city”.

And during the height of this winter’s dock-worker strike on the west coast, we thought we’d surely end up doing the story in Tacoma, Washington. But residents we spoke to didn’t even know anyone who worked on the docks.

All these stories have been covered both by the BBC and many other international and national outlets in the past. But using glass-blowing to clean up the gang-laden streets of Tacoma was one story never covered by mainstream media - even though it’s the first many area residents mentioned to us.

In the end the most interesting finding of BBC Pop Up was not rooted in style, format or workflow. Rather, for me the most intriguing characteristic of the project was the question of whether we as journalists are pushing our own agendas through the stories we choose. Are we misrepresenting regions of the US, or the world for that matter, through our reporting?

Judging by the BBC Pop Up experience, it would appear likely.

Why have there not been more recent stories about corporal punishment in Louisiana, orphaned children in South Dakota or the water supply in Pittsburgh? (These are just some of the few suggested to us that we didn’t have time to cover.)

The reason might be that until now no-one ever asked.

Read part one of BBC Pop Up bureau chief Matt Danzico’s blog

Why mobile video news on Instagram is a fashion we can’t ignore

#BBCTrending’s first question-and-answer session just had to be on Twitter

Engaging social media audiences

How to be a digital innovator: BBC Trending

Digital innovation: Producing video for online and TV

Line between online news video and TV news is blurring

BBC News Labs: The story’s all about making connections

Small communities can have a big impact on your journalism

Five key findings about hyperlocal journalism in the UK