WOMAN: If only other girls would do as I do, I believe that we could manage it alone.

NARRATOR: As the Great War dragged on and more and more men were sent overseas, women had to take on men's jobs. Mabel Lethbridge started to work in Hayes munitions factory at the age of 17.

MABEL LETHBRIDGE: I was put on to a job in bond stores, which was really cleaning detonators. It was very dull work, but the workers were gay and charming and I liked it. The day came when I got the job that I think, subconsciously, I had always been looking for. They asked for volunteers for the danger zone.

NARRATOR: The danger zone was at the heart of Hayes munitions. Set in open countryside, shed after shed marched along nearly two miles of railway track. Working in each was a team of women or boys, packing heavy shell cases with high explosives and detonators.

MABEL: The machines that we were put on that morning were Heath Robinson sort of machines. And so difficult to describe to you, but they were operated, not by machine really, but by a great weight lifted up on ropes by girls behind a pile of wooden boxes. They had no other protection. And they had to drop the weight down on top of the shell. And you were only allowed, say, 12 blows, you would call to the girls, 'Steady, girls,' and they dropped that weight very slowly and you would bring a lever out to stop it. Only, that first morning I was there, some girl didn't call, 'Steady, girls,' but she put her head forward. So the weight came on her head and that was goodbye to her, anyway. A very unhappy feeling for us all.

All the time there were people walking to and fro, emphasising the great danger. And we were continually searched, cigarettes, matches, anything that you might have of metal was taken from you. This went on hour after hour, you were pulled out for a search. And there was a great feeling all the time of tension. A woman came up to me and she said, 'How are you getting on?' I said, 'Well, not very well, it is taking a lot of blows, and the pullers,' who had to pull that great weight up, 'are getting very angry with me.' And my carrier, that's the girl who carries the shells to you and carries them away from you, she's a stacker and a carrier, she said, 'I think the mixture is too cold, it should be hot.' And the overlooker told her to shut up and told me to scrape it all out. And to try again. I said, 'All right.' My carrier, the girl who was helping me to carry the shells, she said, 'I don't like that. I don't like any scraping out.' The whistle blew and we went to the canteen lunch.

NARRATOR: Mabel had only been filling shells for three days. She was still learning the ropes. But after lunch, she volunteered to do an extra shift.

MABEL: At three o'clock in the afternoon, each afternoon, they brought us milk to drink. A trolley came round and we went and we drank this milk. I had been curious and asked why and that's, really, it's to save you from getting the TNT poisoning, it acts as a neutraliser. TNT poisoning was really a yellow poisoning, you went completely yellow and your clothes came off you yellow. It even affected your clothes. I don't know what it was, what it was caused by, it was very unpleasant. You got it very quickly and you carried it, you never got rid of it. It just stayed there, you got more and more yellow. The people looked at you. When you got into a bus or a Tube or anything like that, they looked at you and wondered what was wrong with you. We felt like lepers going home. But on that day…I'd just had my milk and on that day they…we didn't go home like that because…my shell exploded.

NARRATOR: Mabel lost her left leg in the explosion. For her courage, she was awarded the Medal of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

Video summary

Mabel Lethbridge was one of the large number of women who put their lives at risk working in munitions factories back home.

She lost a leg in an explosion in explosion.

As well as the risk of TNT poisoning, working with lethal materials inevitably resulted in fatalities amongst the workforce and the ever-present fear of explosion.

This is from the series: I Was There: The Great War Interviews.

Teacher viewing recommended prior to use in class.

Teacher Notes

Students watch this as an introduction to an investigation into the ways in which WW1 was a ‘total war’.

They have to use the information presented to explain what could be meant by the term ‘total war’, and list the ways in which WW1 could be seen to be a ‘total war’.

This is from the series: I Was There: The Great War Interviews.

Teacher viewing recommended prior to use in class.

This clip will be relevant for teaching History at KS3, KS4/GCSE, in England and Wales and Northern Ireland.

Also at Third Level, Fourth Level, National 4 and National 5 in Scotland.

This topic appears in OCR, Edexcel, AQA, WJEC, CCEA GCSE and SQA.

Life as an officer during WW1. video

Charles talks about coping with looming shellshock and aspects of an officer's life.

One woman's loss. video

Katie describes what the war was like from a young woman’s perspective in Manchester.

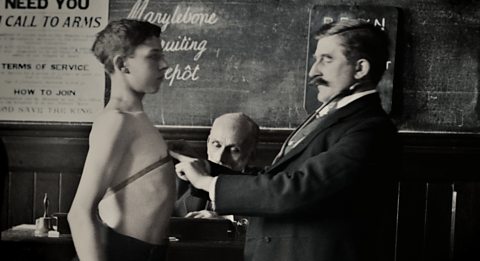

Recruiting soldiers in WW1. video

The different pressures which were applied to persuade young men to join up to fight.

Respite. video

How men could relax and forget about life on the front line when behind the lines and get some respite from the war.

How did shell shock affect soldiers? video

Soldiers from both sides describe their experience of shell fire and the physical and psychological effects it had on them and their colleagues.

The Christmas truce, 1914. video

Henry describes his reaction to being called up and his experiences in the trenches.