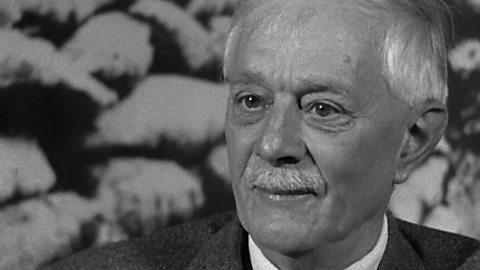

STANLEY F. DOWN: We were relieving men of the 28th division, and as they passed us, they would ask where we were from. And when we said we were from Somerset, they said, "You'll soon be glad to be back there again, mate." And when we would say, "What's it like up there?" The reply invariably came back, "Bloody awful, mate."

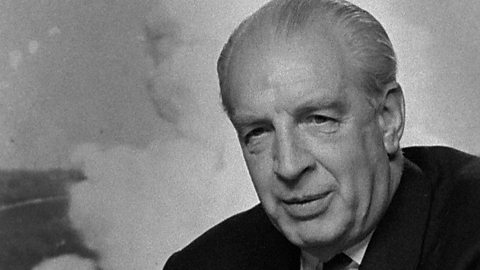

GEORGE T. HANCOX: On the whole, we found it more depressing and disillusioning rather than frightening, first trip in the line. And as we weren't so much frightened of being killed or wounded as we were depressed by the conditions, as we thought we were going to fight a glorious war, and reality was something entirely different.

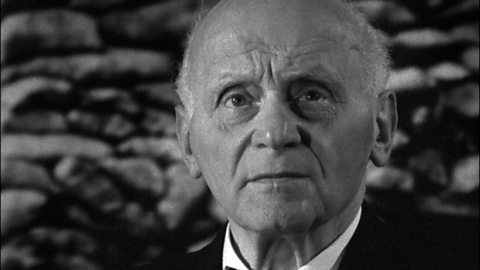

ARCHIBALD G. COCHRANE: I can remember, shortly after arriving in the front line, in the morning, there was what they used to call a "pom-pom." A German gun they used to bring up to their trenches, with a view to popping them into our trenches. They used to go "pom" from their side and arrive into ours with a "pom." Well, they used to enfilade us along, starting on the left-hand side and coming along, and on this particular morning, one reached right up the side of me, and the fella who was on sentry go there was just watching the no man's land to see there was no movement by the Germans, and this shell from the pom-pom arrived and blew half his head off. Well, that was my initiation into death.

CHARLES CARRINGTON: You would hear in the distance quite a mild pop as the gun fired five miles away. And then a humming sound as it approached you through the air. Growing louder and louder until it was like the roar of an aeroplane coming into land on the tarmac. There comes the moment where the shell is right on top of you, and your nerve would break and you'd throw yourself down in the mud, and cringe in the mud till it was past.

REGINALD E. RICHARDS: Some of the shells were passing over you, probably, three foot, four foot. And the air was an inferno. And your mind, of course, was another inferno. Your reason was completely blast out of it.

STEFAN WESTMANN: Our dugouts crumbled. They fell upon us, and we had to dig ourselves and our comrades out. Sometimes we found them suffocated. Sometimes smashed to pulp. Soldiers in the bunkers became hysterical. They wanted to run out and fights developed to keep them in the comparative safety of our deep bunkers. Even the rats became hysterical. They came into our flimsy shelters to seek refuge from this terrific artillery fire.

REGINALD: You were in a maze and you felt that at any time, if you relaxed control, you went haywire. And it was quite a common sight to see people that had relaxed control get up and run around in circles like a sheep. And, of course, they ran around for some time until they met shellfire, which finally finished them.

CHARLES: There were ways in which you could maintain your self-control, and there is some strange connection between small physical actions, if you hum a little tune to yourself, and feel that you can quietly get through this tune before the next explosion, it gives you a sort of curious feeling of safety. Or you start drumming with your fingers on your knee, and have an… quite irrational desire to complete this little ritual. These minute things… protect you from the… nervous collapse, which may come at any moment.

REGINALD: One had no sanity in the business, at all, because you got in this position where the inferno was so blasting that you had no time to think. And you could feel, as you lay down on the ground, you could literally feel your heart pounding against the ground. And that was the sort of condition you found yourself - and then the continuous bombardment, which lasted sometimes for hours. The emotional strain was absolutely terrific. Until, when you got the order to advance, it seemed that it was a sort of a release from that bondage.

Video summary

British, Canadian and German soldiers describe the physical and mental strain of being under shell fire.

They describe the terror and the strange behaviour it caused in some men, and the small strategies others developed to cope with being trapped by incessant shell fire as a way of preventing the onset of shellshock.

Others only found relief when the barrage was lifted and they were instructed to go over the top.

This is from the series: I Was There: The Great War Interviews.

Teacher viewing recommended prior to use in class.

Teacher Notes

Key Stage 3:

Students explore the differing ways that life under shell fire affected soldiers.

They make notes under headings: physical; psychological; short term; long term.

Key Stage 4:

This is used to introduce an investigation into trench life.

It is presented as one interpretation of trench life, and students have to put together a critical view of trench life using this as a piece of evidence.

This clip will be relevant for teaching History at KS3, KS4/GCSE, in England and Wales and Northern Ireland.

Also at Third Level, Fourth Level, National 4 and National 5 in Scotland.

This topic appears in OCR, Edexcel, AQA, WJEC, CCEA GCSE and SQA.

The Christmas truce, 1914. video

Henry describes his reaction to being called up and his experiences in the trenches.

The Gallipoli campaign. video

Frank talks about fighting in the disastrous Gallipoli campaign in 1915.

War in the air. video

Pilots identify the different experiences of men in the air, recalling the realities of combat and the tactics used to down an enemy aircraft.

Being a pilot in WW1. video

Cecil Lewis’ experiences reflect how the role of aircraft changed in the course of WW1.

Fighting in the trenches. video

Stefan Westmann presents two contrasting experiences of the war.

Death and survival. video

The experiences of a disillusioned soldier and the widow of a soldier killed in action