SOLDIERS:

It's a long way to Tipperary

It's a long way to go…

NARRATOR:

The Great War had transformed the role of women in society. But women had no idea of what it was really like for the men at the front.

Goodbye, Piccadilly…

CHARLES CARRINGTON:

This world of the trenches which had built itself up for so long a time, which seemed to be going on forever, was the real world and it was entirely a man's world. Women had no part in it.

NARRATOR:

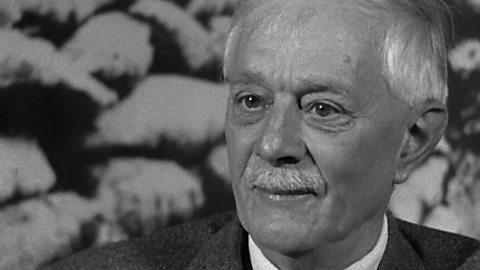

Charles Carrington was just 17 when he enlisted in 1914. By 1917, the long years of war had changed him and his country profoundly.

CHARLES:

When one went on leave, what one did was to escape out of the man's world into the women's world. One found that however pleased one was to see one's girlfriend, and I'm speaking only of the light emotions of a boy, not of the deeper feelings of a happily married man, one could never somehow quite get through, however nice and sympathetic they were, the girl didn't quite say the right thing. One was curiously upset, annoyed by attempts of well-meaning people to sympathize. Which only reflected the fact that they didn't really understand at all. And there was even a kind of last sense of relief in which you returned to the boys. When one went back into the man's world, which seemed the realest thing that could be imagined.

And when they ask us how dangerous it was

Oh, we'll never tell them No, we'll never tell them

We spent our pay in some cafe

And fought wild women night and day

'Twas the cushiest job we ever had…

NARRATOR:

In 1917, British and Allied forces launched an attack in Belgium. The plan was to reach the coast, held by the Germans. The attack lasted for months and became known as the Battle of Passchendaele. Lieutenant Carrington commanded a company at Passchendaele.

CHARLES:

We advanced, just like those battles, under an enormous barrage, a much heavier barrage than I had ever heard before. We ran into a lot of Germans and we had a lot of very severe fighting in the first five minutes, in which I myself got mixed up in a really awkward shooting-out affair. Rather like gangsters shooting it out on a Western film. However, we shot it out and we won that little battle and we got through. By the time we got to our objective, I found that my company was completely scattered. Both my officers, all my sergeants and three quarters of my men were killed or wounded. There was me and the sergeant major and a scattered handful of men which we had to get together somehow. We got them together somehow and we settled down on our objective in a group of shell holes and there we sat for three days. On the second and third days we just sat in the mud, being very heavily and very systematically shelled with pretty heavy stuff. You would hear in the distance quite a mild pop, as the gun fired five miles away. Then a humming sound as it approached you through the air, growing louder and louder until it was like the roar of an airplane coming in to land on the tarmac. There comes the moment when a shell is right on top of you and your nerve would break and you'd throw yourself down in the mud and cringe in the mud until it was passed. There were ways in which you could maintain your self-control. There is some strange connection between small physical actions. If you hum a little tune to yourself and feel that you can quietly get through this tune before the next explosion, it gives you a curious feeling of safety. Or you start drumming with your fingers on your knee. And…and quite irrational desire to complete this little ritual. These minute things protect you from the nervous collapse which may come at any moment.

NARRATOR:

On the third night, under the cover of darkness, Lieutenant Carrington and his exhausted men managed to get out of their shell hole. They scrambled through the mud to the relative safety of a makeshift camp.

CHARLES:

To begin with, I was in a state of complete physical and mental prostration. I think for a few days after the battle I was very near having a nervous breakdown. But when one is young, physical rest very quickly puts that right. In quite a few days I was almost as good as ever. Here I was, I was 20 years old. Young acting captain, and I had to form a new company. I had to begin by actually collecting and organizing the men and finding out what had happened to those who had been killed and those who had been wounded. I had to write 22 personal letters to the wives and mothers of men in my company who had been killed.

We're here because We're here because…

CHARLES:

Then we got a draft of 100 very good men up from the base, then we started all over again and had a new company. At the end of a month, we were ready to do it again. This seems to be the strangest thing of all when I look back on it.

We're here because We're here because

We're here because we're here…

NARRATOR:

Charles Carrington was awarded the Military Cross. After the war, he became an academic and writer. His book, A Subaltern's War, is one of the best-known war memoirs. He re-enlisted at the outbreak of the Second World War, in his own words, 'like an old fool'.

Video summary

Returning home could be difficult for soldiers, as they found it difficult to explain what it was really like to go to war.

In 1917, Charles Carrington took part in the Passchendaele offensive as an Acting Captain, and finding himself cut off in a shell hole with his men had to find a way of coping with looming shellshock.

His account also features the other dimensions of officer life: writing letters to the relatives of deceased soldiers and organising new companies ready to go off and fight again.

This is from the series: I Was There: The Great War Interviews.

Teacher viewing recommended prior to use in class.

Teacher Notes

Could be used to explore life in the trenches or to introduce the effects of the battle of Passchendaele.

This clip will be relevant for teaching History at KS3, KS4/GCSE, in England and Wales and Northern Ireland.

Also at Third Level, Fourth Level, National 4 and National 5 in Scotland.

This topic appears in OCR, Edexcel, AQA, WJEC, CCEA GCSE and SQA.

One woman's loss. video

Katie describes what the war was like from a young woman’s perspective in Manchester.

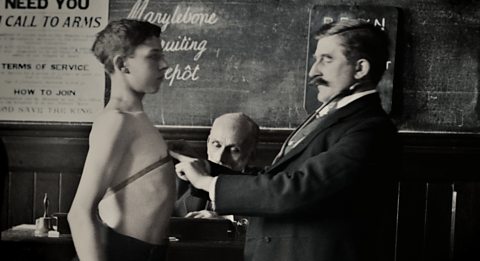

Recruiting soldiers in WW1. video

The different pressures which were applied to persuade young men to join up to fight.

Respite. video

How men could relax and forget about life on the front line when behind the lines and get some respite from the war.

How did shell shock affect soldiers? video

Soldiers from both sides describe their experience of shell fire and the physical and psychological effects it had on them and their colleagues.

The Christmas truce, 1914. video

Henry describes his reaction to being called up and his experiences in the trenches.

The Gallipoli campaign. video

Frank talks about fighting in the disastrous Gallipoli campaign in 1915.