FRANK BRENT: As the war progressed and stunt followed stunt, it required that we should live in animal conditions and, in doing so, it was inevitable that we developed the animal characteristic of killing. And apart from the short feeling of nervousness as you knew that you were moving up to carry out another operation, there was a feeling of exaltation that, once again, you were going to be able to extract retribution from the fellows that had killed your mates.

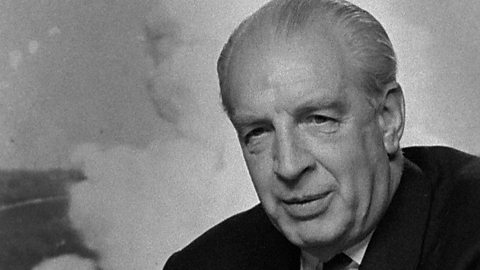

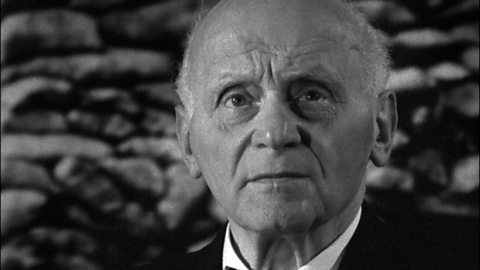

STEFAN WESTMANN: I was confronted by a French corporal, he with his bayonet at the ready, and I with my bayonet at the ready. For a moment, I felt the fear of death. And, in a fraction of a second, I realised that he was after my life, exactly as I was after his. I was quicker than he was. I tossed his rifle away and I ran my bayonet through his chest. He fell, put his hand on the place where I had hit him, and then I thrust again. Blood came out of his mouth and he died. I suddenly felt physically… I nearly vomited. My knees were shaking and I was, quite frankly, ashamed of myself. My comrades, they are absolutely undisturbed by what had happened. One of them boasted that he had killed a French soldier with the butt of his rifle. Another one had strangled a captain. A third one had hit somebody over the head with a spade. But I had in front of me the dead man, the dead French soldier. And how would I liked him to have raised his hand? I would have shaken his hand and we would have been the best of friends. What was it, that these soldiers… stabbed each other, strangled each other, went for each other like mad dogs? What was it that we, who had nothing against them personally, fought with them to the very end, in death? We were civilised people, after all.

ALAN E. BRAY: One evening, I was warned that I had to go on a firing party, six of us, to shoot four men of another battalion, who had been accused of desertion. Well, I was very worried about it because… I didn't think it was right in the first place that Englishmen should be shooting other Englishmen. I thought we were in France to fight the Germans. I thought that I knew why these men had deserted, IF they had deserted, because I understood their feelings which…and what would make them desert. The fact that they had probably been in trenches for two or three months without a break… absolutely broke their nerve.

JOHN W. PALMER: We never had a night's sleep for several nights, and, when you hadn't had rest, and sometimes hardly a meal, it gets you. And you reach the point where there was no beyond. You just could not go any further, and that's the point I'd reached. I was tired of all the carnage, of all the sacrifice that we'd had, just to gain about 25 yards. And then I began to think of those poor devils who had been punished for self-inflicted wounds. Some had even been shot. And I began to wonder how I could get out of it.

ALAN: An old soldier in our battalion told me that it was one thing in the Army that you could refuse, so I straightaway went back to the sergeant and said, 'I'm sorry, I'm not doing this.' And I heard no more about it. I think one reason why I felt so strong about it was the fact that, a week before, a boy in our own battalion had been shot for desertion. Well, I knew that boy and I knew that he'd absolutely lost his nerve. He couldn't have gone back into the line. And he was shot. And the tragedy of that was that, a few weeks later in our local paper, I saw that his father had joined up to avenge his son's death on the Germans.

JOHN: In the distance, I heard the rattle of harness. I couldn't hear much of the wheels, but I knew there were ammunition wagons coming up. And I thought to myself, 'Well, here's a way out. When they get level with me, I'll ease out and put my leg under the wheel. I shall phone to get away and I can plead that it was an accident.' Well, I waited, and the sound of harness got nearer and nearer. Eventually, I saw the leading horses' heads in front of me, and I thought, 'This is it.' And I began to ease my way out. And, eventually, the first wagon reached me. And do you know, I never even had the guts to do that. And I found myself wishing to do it, but hadn't got the guts to do it.

Video summary

War turned ordinary people into killers, which raised a variety of emotions among them.

A German soldier vividly recalls his terrible guilt at killing a French soldier with a bayonet, whilst some of his fellow soldiers boasted about killing during the First World War.

A British soldier recalls refusing to execute deserters from his own side, feeling sympathy for their shellshock.

Another explains in detail how he planned to injure himself to get away from the front, an offence which could result in death by firing squad.

This is from the series: I Was There: The Great War Interviews.

Teacher viewing recommended prior to use in class.

Teacher Notes

Key Stage 4:

Students use this clip to develop contrasting arguments on the merits of pardoning soldiers who were executed for desertion during the war.

This exercise can then lead into a piece of work on how life in the trenches affected soldiers.

This clip will be relevant for teaching History at KS3, KS4/GCSE, in England and Wales and Northern Ireland.

Also at Third Level, Fourth Level, National 4 and National 5 in Scotland.

This topic appears in OCR, Edexcel, AQA, WJEC, CCEA GCSE and SQA.

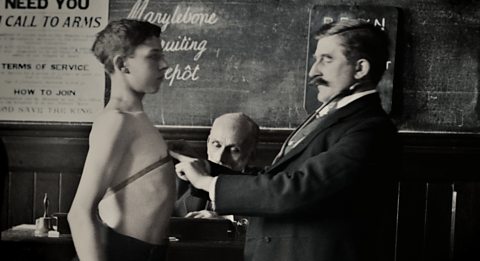

Recruiting soldiers in WW1. video

The different pressures which were applied to persuade young men to join up to fight.

Respite. video

How men could relax and forget about life on the front line when behind the lines and get some respite from the war.

How did shell shock affect soldiers? video

Soldiers from both sides describe their experience of shell fire and the physical and psychological effects it had on them and their colleagues.

Being a pilot in WW1. video

Cecil Lewis’ experiences reflect how the role of aircraft changed in the course of WW1.

Fighting in the trenches. video

Stefan Westmann presents two contrasting experiences of the war.

Changes on the home front during WW1. video

Relatives left at home describe what it was like coping whilst the men were away at war.