Poetry is a very dangerous place. Poetry is never a safe place. And if it's safe, then it's probably not what I'd be interested in. Poetry is on the edge of things. Poetry is pure subversion. It is a way of having a voice about things that you wouldn't dare to speak about otherwise.

Outside the door, lurking in the shadows, is a terrorist. Is that the wrong description? Outside that door, taking shelter in the shadows, is a freedom fighter. The poem wasn't about terrorists. It was about the use of those words. I wanted to think about what words we put onto an image and how we define that image. Because just depending on the words you use, the right word or the wrong word, you can create suspicion or fear or enmity or all kinds of other feelings.

I haven't got this right. Outside, waiting in the shadows, is a hostile militant. A lot of poems start in anger, but they have to become something colder and harder to really work. It may start in the heat of anger, but the anger has to become targeted or the poem can just be a political diatribe or a bit of propaganda or, you know, a rant on the page. There has to be that whole process of making it into something beyond the purely personal or the pure gush of emotion.

Are words no more than waving, wavering flags? Outside your door, watchful in the shadows, is a guerrilla warrior. With all the bombardment of media and language around us, and language very often used crudely, in broad brush strokes, very often poetry has the nuance and the subtlety to bring back the kindness into language, the healing qualities, the nuances. Not just beauty for itself, but the tiny differences that bring a gentleness back into language and into daily life.

God help me. Outside, defying every shadow, stands a martyr. I saw his face. No words can help me now. Just outside that door, lost in shadows, is a child who looks like mine. All of life, you put on personas and masks and different parts of what you are. So there's a definition I gave of myself, which is Scottish Pakistani Calvinist Muslim, adopted by India and by Wales as well. Really what I'm saying is none of us are just one thing. What makes a person?

It may be the songs your grandmother sang you, it may be the food you ate, but every day is also your heritage and culture and you're making it fresh. So that's really what I want to suggest by saying, "I'm all these things, but you are, too." One word for you. Outside my door, his hand too steady, his eyes too hard, is a boy who looks like your son, too.

I started that poem, knowing I was going to take the image and, fairly schematic, I thought, "I'll go through seven different versions of that image." At the end of the poem, when I come to the part where I open the door and say, "Come in and eat with us," the voice becomes completely different. It's not factual, it's not matter of fact. It's a host. And that happens quite often in a poem. The words and the rhythm and the idea itself takes on a life of its own. That's some of the best poems.

I open the door. Come in, I say. Come in and eat with us. The child steps in and carefully, at my door, takes off his shoes.

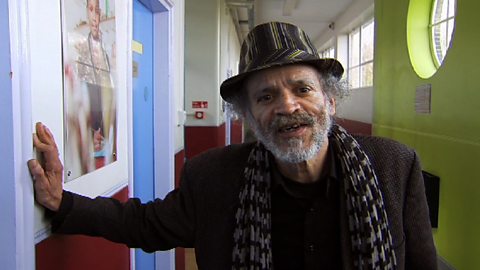

Poet Imtiaz Dharker describes the process of writing her poem 'The Right Word'.

Her commentary is illustrated with footage of urban scenes and her own performance of extracts from the poem.

This is from the series: Poets in Person

Teacher Notes

Can be used to explore the power of language to influence identity.

Students are given a variety of images of different people taken from magazines and newspapers.

Each pair receives an image and one partner composes a few lines of poetry portraying the subject in a sympathetic way eg a picture of a young unkempt teenager, is described as a homeless runaway fleeing an abusive home life.

The partner then writes about the image in a very negative way eg describing the teenager as a criminal or a waster of opportunity.

What conclusions about the power of 'The Right Word' can students draw?

Curriculum Notes

This clip will be relevant for teaching English Literature at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England and Northern Ireland. Also English Language at KS3 and English Literature at GCSE in Wales.

This topic appears in OCR, Edexcel, AQA, WJEC in England and Wales and CCEA GCSE in Northern Ireland.

More from the series: Poets in Person

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'Checking Out Me History' by John Agard (analysis) video

Poet John Agard describes the process of writing his poem 'Checking Out Me History'.

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'Flag' by John Agard (analysis) video

John Agard discusses his poem 'Flag', the symbolism of flags and poetry writing.

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'Ghazal' by Mimi Khalvati (analysis) video

Mimi Khalvati reads and explores the writing of her poem 'Ghazal'.

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'Praise Song for My Mother' by Grace Nichols (analysis) video

Grace Nichols reads and explores the writing of her poem, 'Praise Song For My Mother'.

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'The Right Word' by Imtiaz Dharker (poem only) video

A performance of the poem 'The Right Word' by the poet, Imtiaz Dharker.

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'Ghazal' by Mimi Khalvati (poem only) video

A reading of 'Ghazal' by the author, Mimi Khalvati.

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'Singh Song' by Daljit Nagra (poem only) video

Daljit Nagra performs his poem 'Singh Song'.

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'Checking Out Me History' by John Agard (poem only) video

John Agard performs his poem 'Checking Out Me History'.

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'Flag' by John Agard (poem only) video

A performance of the poem 'Flag' by the poet, John Agard.

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'Praise Song for My Mother' by Grace Nichols (poem only) video

Grace Nichols performs her poem 'Praise Song for My Mother'.

English Literature KS3 / GCSE: 'Singh Song' by Daljit Nagra (analysis) video

Daljit Nagra explores and performs his poem 'Singh Song'.