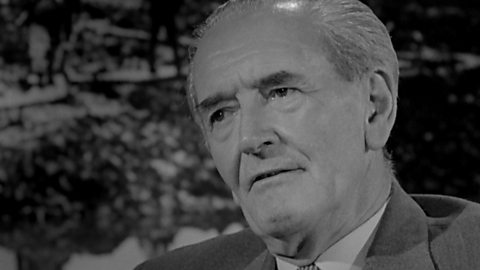

JOHN W. PALMER: There were no times of duty regarding mending telephone wires. Nobody knew when a wire would go, but we knew it had to be mended. The infantrymen's lives depended on these wires working. It didn't matter whether we had had sleep or whether we hadn't had sleep. We just had to keep those wires through.

NARRATOR: John Palmer had one of the loneliest jobs on the battlefield, keeping the field telephones working. These linked the troops on the front line with the command posts and the heavy artillery further back.

JOHN: I had been out on the wires all day, all night, I hadn't had any sleep, it seemed, for weeks, and no rest. It was very, very difficult to mend a telephone wire in this mud. You would find one end and then you would try and trudge through the mud to find the other end. As you got one foot out, the other one would go down. I was tired of all the carnage, of all the sacrifice that we had there just to gain about 25 yards. I think I had reached my lowest ebb.

And then, in the distance, I heard the rattle of harness. I didn't hear much of the wheels, but I knew there were ammunition wagons coming up. I thought to myself, "Well, here's a way out. When they get level with me, I will ease out and put my leg under the wheel. I shall be able to get away and I can plead it was an accident." Eventually, I saw the leading horses' heads in front of me. I thought, "This is it." I began to ease my way out and eventually the first wagon reached me. You know, I never even had the guts to do that. I found myself wishing to do it, but hadn't got the guts to do it.

Well, I went on and I finished my wire, I found the other end and mended it. I was out twice more that night. I was out next day. The next night, my pal came out with me. He wasn't busy on the other wires. And after the Germans had stopped shelling a little while, we heard one of the big ones coming over. And normally, within reason, you could tell if one was going to land anywhere near or not. If it was, the normal procedure was to throw yourself down and avoid the shell fragments. This one, we knew, was going to drop near. My pal shouted and threw himself down. I was too damn tired even to fall down. I stood there.

Next, I had a terrific pain in the back and the chest and I found myself face downwards in the mud. My pal came to me, he tried to lift me up. I said to him, "Don't touch me, leave me, I have had enough. Just leave me." The next thing, I found myself sinking down in the mud. This time, I didn't worry about the mud, I didn't hate it any more, it seemed like a protective blanket covering me. I thought to myself, "Well, if this is death, it is not so bad."

I found myself being bumped about. I realised that I was on a stretcher. I thought, "Poor devils, these stretcher bearers are. I wouldn't be a stretcher bearer for anything." And then something else happened. I suddenly realised that I wasn't dead. I realised that I was alive. I realised that if these wounds didn't prove fatal, I should get back to my parents, to my sister, to the girl that I was going to marry. The girl that had sent me a letter every day, practically, from the beginning of the war. And I must then have had that sleep that I so badly needed. For I didn't recollect any more until I found myself in a bed with white sheets and I heard the lovely, wonderful voices of our nurses, English, Scotch and Irish. And I think then I completely broke down.

Next, the padre was sitting beside the bedside. He was trying to comfort me, he told me I had had an operation and he told me that he had some relatives out there that had been out there right from the beginning and, by God's grace, they hadn't had a scratch. He said, "They've been lucky, haven't they?" I thought to myself, "Lucky? Poor devils."

Video summary

The war affected combatants in different ways.

Whilst some were able to detach themselves from its horrors and focus on the job of ending it quickly, others, such as John Palmer, a signaller, found it increasingly difficult to cope with the violence and apparent pointlessness of the conflict.

He only found respite after being seriously injured, in the hope of returning home to his family.

This is from the series: I Was There: The Great War Interviews.

Teacher viewing recommended prior to use in class.

Teacher Notes

This clip could be used to explore the reasons why some soldiers thought the war was pointless.

Students could be asked to provide a ‘back story’ to this soldier’s experience at the front explaining why he might have adopted these attitudes towards the war.

This clip will be relevant for teaching History at KS3, KS4/GCSE, in England and Wales and Northern Ireland.

Also at Third Level, Fourth Level, National 4 and National 5 in Scotland.

This topic appears in OCR, Edexcel, AQA, WJEC, CCEA GCSE and SQA.

Attrition. video

The strains of war drove soldiers to desert their post or inflict a wound on themselves.

Life as a munitionette. video

Mabel was one of many women who put their lives at risk working in munitions factories.

Life as an officer during WW1. video

Charles talks about coping with looming shellshock and aspects of an officer's life.

One woman's loss. video

Katie describes what the war was like from a young woman’s perspective in Manchester.

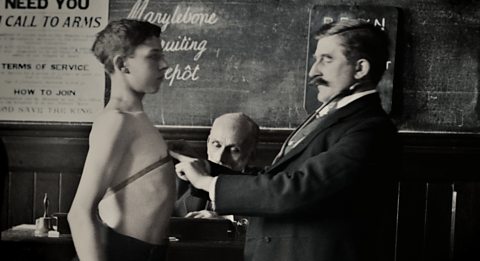

Recruiting soldiers in WW1. video

The different pressures which were applied to persuade young men to join up to fight.

Respite. video

How men could relax and forget about life on the front line when behind the lines and get some respite from the war.