Viewing shocking eyewitness media is ‘as traumatic as frontline reporting’

Sam Dubberley

is co-founder/director, Eyewitness Media Hub @samdubberley

A study published by Eyewitness Media Hub sheds new light on the extent of secondary trauma suffered by journalists exposed to a regular stream of disturbing material on social media. Its lead author samples the survey’s findings and suggests some solutions:

While most reporting of international conflicts, man-made or natural disasters was once done by journalists from news organisations, by agencies or local partners on the ground, we can now stay in the safety of our offices and wait for the content to come to us. Where we used to have one front line, we now have two: the geographical front line and the digital front line.

And the amount of content that’s out there - the number of videos filmed every day and uploaded to YouTube, Facebook, Vine, the images captured on Instagram, the live events shared on Periscope and Meerkat - only grows, day by day.

That all this has changed the face of newsgathering is frequently discussed at media conferences, even in news bulletins. What is discussed much less frequently is the impact on the journalist - the human being looking at this horror, day in, day out.

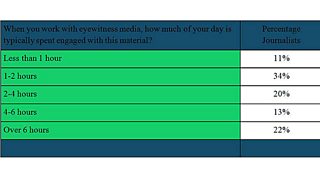

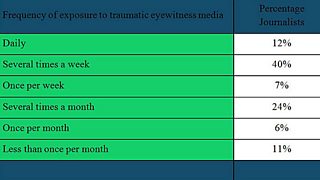

Our latest research (Making Secondary Trauma a Primary Issue: A Study of Eyewitness Media and Vicarious Trauma on the Digital Front Line) found that journalists tasked with newsgathering through social media look at this content a lot.

And a lot of it is traumatic – 42% of journalists who work with social media see traumatic content several times a week.

The journalists on both front lines see horror on a regular basis. While a foreign correspondent may be reporting the aftermath of an earthquake, a social media producer could be searching for videos from the aftermath of the latest barrel bombs to be dropped on Aleppo.

Here are some of our headline findings:

- Staff at news organisations’ headquarters who work with eyewitness media often see more horror on a daily basis than their counterparts deployed in the field.

- 40% of the 209 respondents to our online survey said that viewing distressing eyewitness media has had a negative impact on their personal lives. They’d developed a negative view of the world, felt isolated, experienced flashbacks, nightmares and stress-related medical conditions. Many interview respondents reported suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or had referred themselves to professional counselling. Some had resigned from successful careers where they’d received no organisational support.

- Unexpected exposure to distressing eyewitness video was almost universally cited by interviewees as having a more traumatic impact on them than distressing material that the individual was prepared to view.

- Sound was reported to be one of the most distressing elements. Interviewees spoke of the sound of children in distress; hearing violence; the utterance of last words; people pleading for their lives and the screams as they die as being amongst the most traumatic things to hear.

- Professionals who told us that they have suffered from vicarious trauma are less likely to feel comfortable requesting help from their managers. When asked how comfortable they would feel in speaking to their manager about the impact of traumatic content, 68% of journalists who reported experiencing no vicarious trauma told us that they would feel comfortable, if they did. For those who felt that such trauma had impacted on their personal lives, only 35% said they would feel comfortable approaching a manager.

- Despite some improvement in acknowledging vicarious trauma and an emergence of support, resources are still not widely available to help staff who are working with distressing eyewitness media. Only 23% of our survey respondents had access to peer support networks. A mere 24% had access to relevant training, and only 31% had regular debriefs with their managers. Despite this, respondents reported that these resources, along with taking regular breaks from work, were considered the most useful to help mitigate the effects of viewing upsetting eyewitness media.

Do journalists always need to watch 'execution' videos to the end? BBC News used this 2014 image of hostage Alan Henning, taken from footage posted by so-called Islamic State, purporting to show his beheading

So what can help?

Our research found a number of tips that seem to help people impacted from newsgathering though social media. Many of these centered around recognising that vicarious trauma can be an issue for yourself and your colleagues: one of the most important points raised by journalists was that an organisation should have the culture within it to destigmatise any adverse impact.

Our recommendations, based on the research

- Recognise that it is an entirely normal human reaction to experience negative emotions as a direct consequence of viewing traumatic images, in particular when one views such images regularly and for prolonged periods.

- If you are experiencing negative emotions or feel that you are displaying symptoms of vicarious trauma, do not feel guilty and/or ashamed. You are not alone in experiencing such feelings.

- Be aware that working with distressing eyewitness content in an office can be as traumatic as working in the field because you’re likely to be viewing far more graphic and disturbing acts on a more frequent basis.

- If you think you are experiencing symptoms of vicarious trauma or any other mental health condition, talk to someone you trust - a family member, friend, colleague, manager or mental health professional. Never isolate yourself or feel ashamed of expressing how you feel. Do not feel ashamed or guilty about seeking professional counselling.

- Develop healthy coping mechanisms in the office that you can incorporate into your daily routine, including taking regular breaks and getting out of the office every so often. Take time out to view positive images or read light or inspirational literature. Where possible, limit your exposure to traumatic material - ask yourself and your colleagues and managers (where you feel able) if you really need to view a particular image that you might find distressing.

- When viewing strong material, minimise the sound, pause the video periodically and move away from your desk before completing the viewing. If you know that the video ends with an execution or an extreme act of violence, ask yourself whether you really need to watch the whole video to gain the information that you need to do your job.

- Ensure that you do not share distressing content with colleagues without warning them. Unexpectedly viewing upsetting material can cause additional distress and trauma.

- Try to identify the specific type of traumatic eyewitness media that has a more disturbing impact upon you. Where possible, let colleagues and managers know that you find particular types of content (featuring children, for instance) most traumatic.

- Request that your organisation engages professional mental health experts to provide training and support on vicarious trauma.

Perhaps most crucially, managers and organisations need to take this issue seriously. As an industry, we have to understand that, with each new piece of media technology there will always be new ways for journalists to be exposed to the horrors of the world, in ways never previously imagined. We’re, of course, not saying that journalists shouldn’t embrace these new technologies. We’re just saying that it’s important to try to ensure that we don’t end up traumatised in the process.

The full research report is available on the Eyewitness Media Hub website.

Eyewitness media: Newsrooms must handle it better or risk losing out

Eyewitness media and news: It’s still a Wild West out there

Eyewitness media: ‘Valued stop-gap but no match for professional journalism’

Our journalist safety section deals with various aspects of trauma